First, I’ll reintroduce myself — I’m Susie Compton, a first-year PhD student specializing in 19th century American literature, primarily the writers of the American Renaissance (with Emerson & Whitman tying for first place as my favorite American geniuses). I had a very traditional undergraduate experience majoring in English, since my department at Wash U offered lots of survey courses (“Shakespeare,” “Modernism,” “American Literature to 1865″) to fulfill requirements and, I would say, emphasized the canon over non-canonical works. I also was not forced or prompted to explore theory too much, so while I do feel that I have a good foundation in literature, my arrival to graduate school has very much been an exploration of what else is out there. As such, digital humanities is very new to me, and I will wholeheartedly embrace being the novice in the classroom.

I’m about halfway through the readings and I’m already excited. Clifford has already noted the emphasis on “doing” in digital humanities, which I also noted as an important element of the DH realm. It’s something I’ve mentally struggled with before, because I’m a fairly digital person who utilizes social media and technological tools, but how would I make these tools work for my academic side? (You’ll note that I chose to create a new Twitter handle, @academicsusie, to differentiate from the more everyday musings of @susiecompton — I don’t know why I feel this compartmentalization of digital identities is necessary, but I think it will help me focus my various “feeds”). Because I specialize in the 19th century, I’ve also struggled with bridging that gap between the 19th and 21st centuries. Nigel’s Twitter bio is wittily apt: “I like really old things and really new things. Everything in between in just filler.”

While perusing Day in DH blogs, I came across a link to The American Literature Scholar in the Digital Age, where I read about case studies using the Walt Whitman archive, textual transmission, scholarly collaboration, etc. I’ve obviously always been aware that there are huge digital projects focusing on the 19th century out there (Martha Nell Smith is in our midst, after all) but to come across this collection of essays while exploring what is an unfamiliar world of DH, it helped to ground me in what I already know.

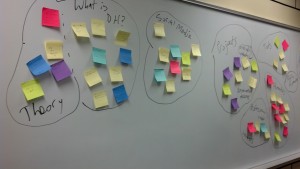

But enough personal narrative; my “introduction” to DH through our various readings has provided me with a few key ideas about “what DH is.”

It’s certain that there’s an overlap between these fields and that which has been called digital humanities—between scholars who use digital technologies in studying traditional humanities objects and those who use the methods of the contemporary humanities in studying digital objects—but clear differences lie between them. Those differences often produce significant tension, particularly between those who suggest that digital humanities should always be about making (whether making archives, tools, or new digital methods) and those who argue that it must expand to include interpreting. (Kathleen Fitzpatrick, “The Humanities, Done Digitally”)

I’ve already mentioned the theme of “doing,” or “making,” but I’m also interested in digital interpretation–what I would describe as using digital tools to interpret what is already available to us as a text. I think this area of digital humanities is where we welcome the DHers who can’t code or build archives, but they are fluent enough in DH “theory” (which I’ve yet to be able define) to capably use the tools others create. So DHers aren’t “every medievalist with a website,” but every scholar who can navigate the digital realm of humanities.

Jamie Bianco’s “This Digital Humanities Which Is Not One” helps in thinking about creation vs. criticism (or making vs. interpreting). He writes,

Tools don’t reflect upon their own making, use, or circulation or upon the constraints under which their constitution becomes legible, much less attractive to funding. They certainly cannot account for their circulations and relations, the discourses and epistemic constellations in which they resonate. They cannot take responsibility for the social relations they inflect or control. […] Tools may track and compile data around these questions, visualize and configure it through interactive interfaces and porous databases, but what then? What do we do with the data?

So, within DH, there are clearly tools, tool-makers, data, and interpreters. Tool-makers and interpreters can certainly overlap, but like I said, I don’t think they have to. And, like Bianco implies, a tool is useless if not examined. An archive is more than a resource, it offers potential for fresh interpretation — and more “doing.”

Rafael Alvarado acknowledges that DHers have varying levels of “technical expertise,” opining that,

The digital humanities is what digital humanists do. What digital humanists do depends largely on academic discipline but also on level of technical expertise. [...] The task of the digital humanities, as a transcurricular practice, is to bring these practitioners into communication with each other and to cultivate a discourse that captures the shared praxis of bringing technologies of representation, computation, and communication to bear on the work of interpretation that defines the humanities. (Day of DH)

So perhaps we can all be DHers in our own ways (this, not surprisingly, coming from the novice with little to no “skills”) and the point of DH, as Alvarado says, is to put us into communication with one another, in order to more collaboratively interpret our areas of literary interest. Having made an effort to participate in DH on Twitter for approximately four days now, I can already see how rich this communication is (it’s kind of insane). Every ten seconds, it seems, there’s a new link to follow, a new blog post to read (not to mention the archived blogs you could retroactively explore), etc. I liked what Ernesto Priego wrote in his Day of DH blog post re: blogging:

In blogging, “yacking” is “hacking”. More importantly, “yacking” is “hacking” because it is meant to happen in a network: a blog, in my view, should not aspire to be the centre of anything, but to be a node in a larger constellation of nodes.

This type of thinking inspires me to believe that DH is one of the least self-centered realms of academia. In my mind, almost nothing is more self-indulgent or narcissistic as writing a blog, but it seems true that in the DH world, sharing and communicating negate the existence of a center (as Priego says) and instead formulate a “constellation of nodes.”

I’m not entirely sure that I’ve gotten too far in “defining” Digital Humanities for us here (I think I focused more on “What is a DHer”), but it’s certainly been a fruitful “introduction.” And, as I said, I’m only about halfway through our reading, so we’ll see what else is out there–and what everyone else has to say!