I wrote a blog post on the composition of my Twine story if anyone is interested.

Author Archives: Dan Kason

Hypertext, Doubles, and Weirdness

Playing through “weird tape in the mail” is, as expected, a weird experience in itself. I have read/played hypertext stories/games before (mostly when I was a kid), so the experience and set-up here was more or less familiar. Dickinson offers two different ways to click through the story, both of which are functionally the same but presented differently: the reader either clicks on a word within the text to reach the next page, or a choice is offered to the reader at the end of the page. These choices branch out slightly and can lead to different scenarios in the story, but from what I can tell these options are limited and, with the exception of the ending, usually circle back to the same starting point.

A word about style: the aesthetic here is minimalism which borders on crudeness. Dickinson does not use capital letters or punctuation. This choice, rather than an homage to E. E. Cummings or anything like that, seems more a reflection of the story’s medium. Dickinson’s simple, direct, casual, and purposefully clumsy writing makes sense for a piece that exists on the internet. The Microsoft Paint illustrations also reflect this aesthetic (or anti-aesthetic).

But is that all there is? As the story goes on and events get more and more “weird,” suddenly these laughable illustrations take on a different quality. They become creepy. There is a disconnection between the laziness of the drawings and the growing seriousness of the story that is quite terrifying. Does Dickinson’s use of language also capitalize on this irony? Or was this choice as simple as a representation of internet culture as I originally thought?

The story itself is quite interesting. The doppelganger narrative is an obvious but clever representation of what hypertext adventure games and stories are all about. By granting the reader agency, however limited, hypertext stories bridge the gap between the reader and the character. “Weird tape in the mail” is written in the second person so that “You” become the main character. To confront another “you” is a metaphor for the experience of clicking through the story itself, and just how bizarre this experience can feel.

There are other elements of the story that are not quite as obvious or clear. I was confused by Dickinson’s incessant “critique” of consumerism. Very quickly, these references to the addiction of buying and having to consume became parodies of themselves. This tired critique of capitalism is only interesting for its in-your-face quality, but how does it connect to the other threads of the narrative? Is it also a metaphor for the experience of hypertext fiction? Do we want to speed through these clickable pages in order to get the satisfaction of having consumed it? Or am I giving Dickinson too much credit?

Another idea is that this interest in consumerism is really about the issue of agency. During the dream segments of the story, you become a mindless consumer with the singular goal of buying products. If hypertext fiction is a medium about choice and the agency of the reader, what does this reduction of the protagonist (you) to a mindless robot say about the reader in general? This idea is a bit more interesting, but why is this already parodist critique of capitalism necessary to reach this discussion of agency? Regardless, Dickinson clearly wants these issues to be central to the tale, as one version of the ending occurs in a mall with customers shopping aggressively and ultimately trampling you to death.

The other version of the ending involves your being killed by your own doppelganger in the bathroom. These endings are radically different (even if you are killed in both) and support the claim that the reader indeed has some say in how his or her story progresses, even if it must lead to the same result. You are given the option of “rewinding” to try out each or both endings, rather than starting from the beginning, so these choices may not have the same consequences for the reader as other stories. Nevertheless, Dickinson has some investment in how a story progresses and who decides, even if there are only a limited number of options available.

“Weird tape in the mail” is an enjoyable story and a clever commentary on its medium and genre. Even if I cannot understand all of Dickinson’s stylistic and story decisions, I will certainly never look at my toilet the same way ever again.

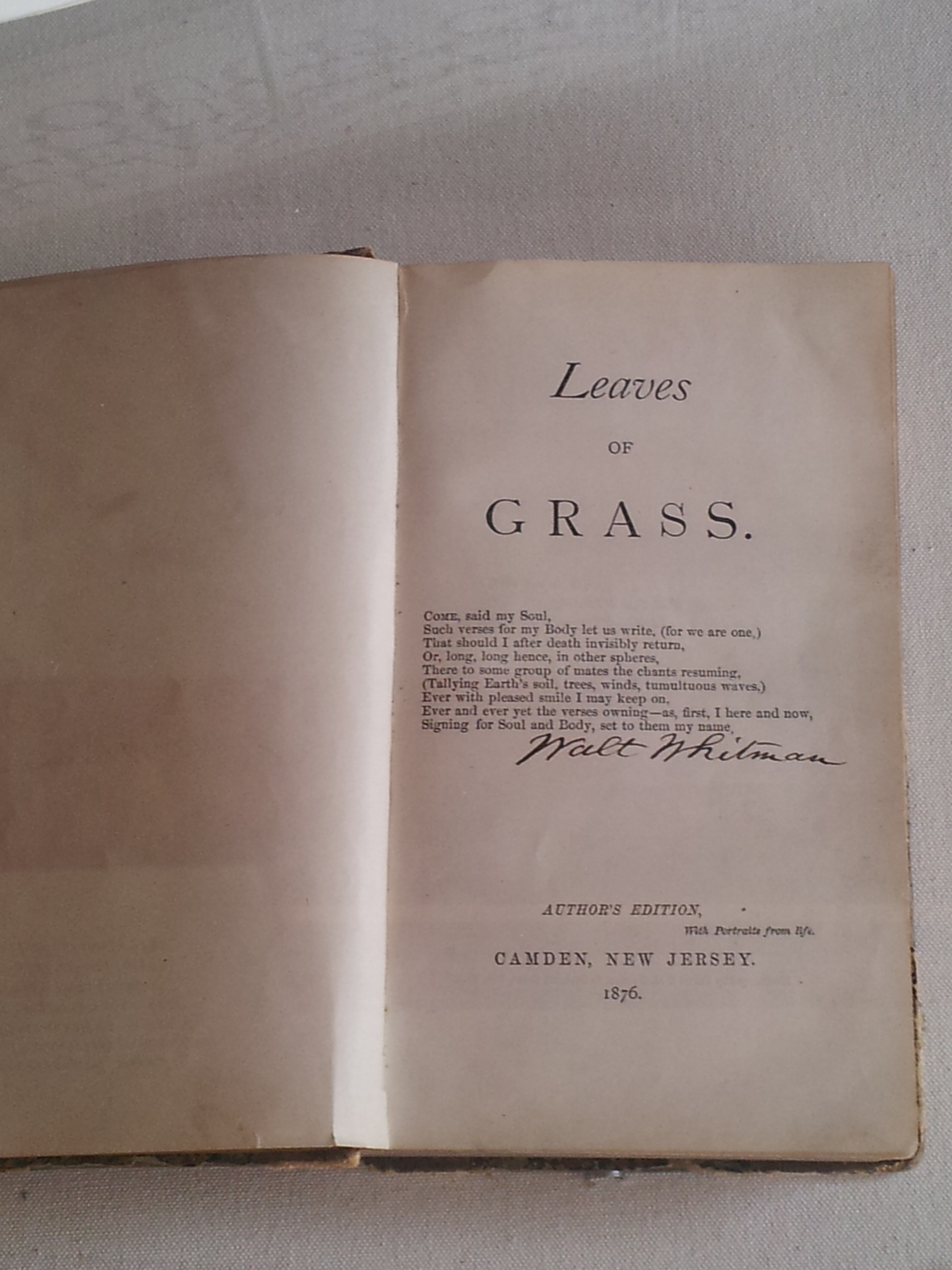

When I Heard the Learn’d Digital Humanist

I decided to visit Walt Whitman’s birthplace, located in Huntington Station, NY, for several reasons. I’ve been meaning to visit the house for a long time, even though it lies only 10 or so miles from my parents’ house. I also attempted to teach a few Whitman poems earlier this semester. In the past I would drive by the site all the time, frequent the nearby Walt Whitman Mall, and was aware of Long Islanders’ pride in their favorite poet’s origins. I suppose next I’m supposed to visit the home of Billy Joel, from a town known as Oyster Bay, Long Island.

I took a tour of the grounds and the house itself, where Walt Whitman Sr. practiced carpentry. I walked through the parlor, kitchen, master bedroom, spare bedroom, and servant’s quarters. As you can imagine, everything looks very old, and it would have been quite easy to hit my head on the low ceiling going up the steps. The Whitmans owned a host of useful tools that are no longer necessary anymore, such as a giant loom, bed rope stretcher stick (can’t remember what it is actually called, but apparently this is where the saying “sleep tight” comes from), and even a hoop and stick.

My visit to Walt Whitman’s birthplace was quite enjoyable. Many thanks to my father for joining me on his busy Sunday afternoon.

Note: I could not secure a more significant spot to place the QR Code, such as the statue, the house, ect., as I was being watched by the tour guide and did not want to get kicked out for vandalism. So the grass would have to do. For some reason the picture does not work when I try to scan it with my phone (bad resolution?), so I also included the original code file.

In Response to Farman

Quoted from Jorge Luis Borges

A map is only useful as a representation, which necessarily involves a distortion of reality. Google Earth threatens this idea by purporting to represent reality with a new degree of accuracy and comprehensiveness, and yet we cannot escape the old problems. Instead, these problems are magnified through the illusion of objectivity and accuracy which Google Earth promises to deliver.

Issues of supposed interactivity and user-based generated content complicate this issue, but as Farman admits, these tools, allowing for a new degree of freedom, are also controlled and regulated by Google. Not only this, but even the choices made by individuals reflect ideologically and politically-based biases, so even if democratizing the creation of maps eliminates or at least mitigates the centrality of power for the mapmaker, it could never eliminate the inherent subjectivity of mapmaking itself.

Instead, by attempting to create such a map of perfection, Google Earth’s supposed potential for subversion is even more dangerous than the old, less accurate maps. Maps continue to create boundaries, rather than represent them, but with an even greater degree of power and influence due to the illusion of objectivity within Google Earth.

This is a postmodern issue because here the distribution of power is not one-sided (as in a user watching a TV), and neither is the direction reversed (the TV is watching you), but now neither the source of power nor its direction is clear. Agency is no longer known or definite. For Farman, this is a positive thing, but if we wish to continue this postmodern critique (which I believe I have been lifting from Jameson, but I can’t be sure), we could argue that by using technology in order to extend the potential of maps to their absolute limit, Google Earth is even more deceptive than traditional maps. The more a representation resembles its original, the easier the viewer is fooled by its supposed authenticity. Google Earth takes this logic and adds with it the possibility of collaboration and interactivity, thereby ensuring that with this controlled potential for subversion, the user will be even more fooled by its illusion of objectivity. At this point, Foucault’s panopticon no longer bears any relevance, as the source and directionality of agency is lost or obscured, legitimizing Google Earth even further.

This is a pessimistic view of the function of Google Earth, but it fits into the Jameson and Baudrillard postmodern critique to which Farman alludes. Instead, he arrives at a more positive view of the functionality of Google Earth, recognizing its limitations but nonetheless embracing the certain degree of subversion somehow allowed by its creators. While I would like to agree with Farman, who begins to recognize these issues but doesn’t quite see them through, it would be foolish to ignore how easily Google Earth fits into this critique.

Transcribing Bentham, or: Jeremy, Why Couldn’t You Have Better Handwriting?

My transcription and encoding experience was largely positive, but I must admit up front that I opted to take the “cheating” route and select a manuscript not handwritten directly by Bentham, but by one of his more legible copyists. I came to this decision after perusing through manuscript after manuscript and struggling even just to get through the first line. Deciphering handwriting can be a useful skill, but it is one I do not have, apparently. Ironic, considering my own awful handwriting.

I ended up working with JB/116/292/002, although I am not sure how I reached this point. The tool bar and encoding process itself is quite accessible and easy to use, but the interface for finding a manuscript could use some more features (although the pick a random manuscript button is pretty neat).

Since I “cheated” on this assignment, I did not run into too much trouble while transcribing and encoding this particular copyist’s beautiful handwriting. Perhaps the only word that gave me any trouble now seems obvious, but it did take some help from my roommate before I saw it for myself:

Spoiler alert: the answer is “interwoven.” Yes, yes, I know it’s obvious, but apparently I have a lot to work on when it comes to deciphering handwriting. I am a big fan of this project as a collaborative endeavor, though, and it was a small thrill to get an email from the editors saying my transcript has been accepted. I have now made my small but noticeable contribution to such a huge project, and this acknowledgment does make me feel pretty important. If I can somehow improve my skills in this area, perhaps I can contribute more!

Experimentation, Machines, and The End of the World

This might just be me taking any excuse I can find to talk about an author I like, but the writings of Stanislaw Lem do seem relevant to DH work. Specifically, “How The World Was Saved” applies well to the principles of something like text analysis or topic modeling.

In the story, Trurl (a robotic engineer/constructor) builds a machine that could create anything starting with the letter N. Already this enacts a constraint, from which Trurl can create and build. Trurl must learn to work within this limit (and it is quickly established that there are no shortcuts to get outside of the machine’s programming). The difference, of course, is that what this machine creates also exists in the real world. In other word, by limiting its contents (or data) to a finite number, the programming of the machine enacts a “deformance” on the universe, as if it were a text.

We can also relate Trurl’s machine to the theory vs methodology debate. Trurl doesn’t approach the machine with a specific question he needs answering or an end result he would like to achieve. Instead, Trurl experiments, feeding the machine words and testing the limits of its programming. To relate this to Fish, Trurl does not begin with an interpretive hypothesis that needs answering, as is typical in the humanities. Likewise, he doesn’t apply this hypothesis to the machine’s results and look for a formal pattern. In DH, the direction is reversed (witnessing a formal pattern and then formulating an interpretive hypothesis). Trurl takes the DH approach.

Unfortunately for Trurl, the word he uses to reach this point, “Nothing,” nearly destroys the universe. But what is interesting is how the machine responds to Trurl’s command:

Had I made Nothing outright, in one fell swoop, everything would have ceased to exist, and that includes Trurl, the sky, the Universe, and you – and even myself. In which case who could say and to whom could it be said that the order was carried out and I am an efficient and capable machine?

Trurl’s experiment with “Nothing,” which unfortunately eliminates all of those “worches” and “zits,” can be considered the outlier in the machine’s results. It represents a moment in which, in order to follow both its programming and its command, the machine must alter its methodology somewhat (not to mention the universe itself). This might be the type of result we look for when running topic models or text analyses: the ones that confront what the tools struggles or fails to do or even strains itself doing.

Of course, Trurl’s machine is just science-fiction and doesn’t technically exist, but I wouldn’t mind experimenting with it myself.

(Side Note: Another of Lem’s stories, “Trurl’s Electronic Bard,” could have easily been the subject of another blog post, applying particularly well to our discussion in the first few weeks. But don’t worry, I’ll spare you the long-winded essay . . . for now.)

Art and Science as Complementary Opposites

I was very drawn to the argument Ramsay puts forth in Reading Machines. This might be because out of all of the readings thus far (okay, only two week’s worth of reading, but last week had a good amount of material . . .), Ramsay most willingly acknowledges the divide between humanistic inquiry and computational method. Indeed, as Ramsay argues, while each contains a kernel of the other, algorithmic criticism seeks definitive answers, while literary criticism seeks unanswerable questions.

In this blog post I will try to focus only on “Preconditions” and the first chapter, “An Algorithmic Criticism,” of Ramsay’s book, perhaps setting my own constraints for myself. I do this to save the rest of my thoughts for class on Wednesday, and I will use this post as a jumping-off point for discussion.

It is difficult to explain why the pairing of two opposing modes of inquiry fascinates me. This discussion reminds me of the interests of early science fiction writers, who, influenced by the Romantic period, used the very methods of rationalism and science as a form of critique. Ramsay nearly states exactly this in his discussion of art and science:

“Art has very often sought either to parody science or to diminish its claims to truth.”

With this ever-present tension, how could we possibly use text analysis to aid literary criticism in a way that does not remove the basic tenets of humanistic inquiry? Ramsay has a few answers to this. Computer-based tools represent a limitation that allows us to reorganize and understand a text in new ways. While text analysis can only concern itself with verifiable facts, the user is left to decide what to do with these “facts.”

In other words, computer-based tools like text analysis often act as a form of provocation, a starting point for us to delve deeper into an issue. I certainly encountered this in my own limited/crude experiment with Woodchipper, a topic modeling tool. The fear that comes with using many of these tools—and here I might break my own constraint and reach into the other chapters—is that they can only tell us what we already know. This might be a problem with methodology, as Ramsay points out. The more worthwhile experiments are the ones that tell you things that suggest the opposite of what you believe. Certainly as computer-based tools grow more complex and sophisticated, they will be able to give us answers to questions we previously believed only humans could address. But Ramsay is more interested in discourse rather than methodology:

“. . . we can refocus the hermeneutical problem away from the nature and limits of computation (which is mostly a matter of methodology) and move it toward consideration of the nature of the discourse in which text analysis bids participation.”

Another issue which Ramsay may or may not address is that while you can produce results using text analysis (and other tools) without having read the text in question, you may not be able to interpret those results. This is certainly true for Ramsay’s experiment with The Waves. As Ramsay points out after running an equation regarding the speakers in the novel,

“Few readers of The Waves would fail to see some emergence of pattern in this list.”

But what if you haven’t read The Waves? It is a short book, and one you would certainly be expected to have read if you decided to publish anything, including an experiment with text analysis, on the novel. But this issue becomes a problem when we consider “distant reading,” which purports not to require any general or specific knowledge of the text. In fact, distant reading discourages it.

But if you cannot interpret the results unless you have read the book in question, how are we supposed to approach the topic: “How to Read a Million Books.”? Even when we consider a hundred or a thousand books at once (or millions, as described in the TED talk video), it might be helpful to know at least a few things about each one, like the fact that The Waves features six speakers.

Here is where methodology asserts its importance once again. Only when a computer-based tool becomes sophisticated enough to allow for interpretive analysis without engaging with the text directly can these tools usurp the primacy of the reader. Perhaps we have reached this stage already, but I cannot help but cling to the importance of close reading, even as we compare a work to hundreds, thousands, or even millions of others.

Mapping Scarlet Letters

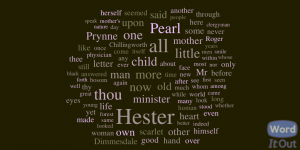

Wordle and WordItOut

To start, I decided to place the text of The Scarlet Letter into Wordle and WordItOut and compare them side by side. Here are the clouds I created. First, Wordle:

Nothing too surprising here. And yes, I kept all the defaults. On to WordItOut:

I kept the layout simple for easy reading. As you can see, both word clouds are quite similar, and the content of the words isn’t surprising. Names are quite prevalent, with Hester and Pearl topping the list. Words like “Heart,” “Life,” and “Mother” get at the core issues of the novel. WordItOut represented quite a few more mundane words that don’t mean much on their own: “within,” “among,” “whether,” “indeed,” “even,” ect., while Wordle came up with more interesting results overall, though many of these words appear small due to their low frequency. In particular, the category of morality pops up, which shouldn’t be surprising for someone that has read the novel: “soul,” “sin,” “shame,” ect. Finally, while admittedly a common word, the large frequency of “One” is a bit puzzling, but something to take note of for later.

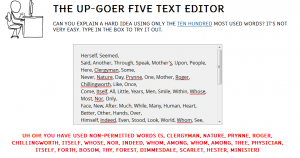

Up-Goer Five Text Editor

Up-Goer Five Text Editor is an interesting experiment in constraint. It does for the depth of language what Twitter does for length. It took a bit of rewriting before I got a definition of the Digital Humanities that didn’t seem horrible: “The use of computers in order to find new ways of doing and making while focusing on older ways of understanding.” Wow, does Up-Goer Five Text Editor require simplicity or what? Already I was ready for a few rejected words, so I put my results from WordItOut into the box and clicked enter. This is what I found:

Most of this isn’t too surprising. I did not expect names like Prynne and Chillingsworth to be among the ten hundred most used words. Moreover, words not in use anymore, such as “thee” and “thy,” were rejected, although I was surprised and disgusted by the rejection of “whom.” You would think a word like “itself” would appear, but this demonstrates just how limited you must make your vocabulary in order to use this tool. This was an amusing experiment, and the constraint works in a similarly way as Twitter, forcing the user to create something under set limitations.

CLAWS Part-of-Speech

Next, we move on to CLAWS part-of-speech tagger, which is a fun experiment, but not quite as amusing as the other tools. I would have appreciated a function that sorts the words of alike parts of speech together, but I suppose you cannot ask for everything. From what I can tell, there is actually a variety of parts of speech here, with proper nouns, reflexive pronouns (the prevalence of “self” is interesting), adverbs, singular nouns, prepositions, pronouns, and more. Could I have discovered this on my own? Probably. But CLAWS brings these facts to my attention as a way of sparking new questions or pursuing new areas of study. But for now I’ll leave CLAWS alone and move on to the final tool.

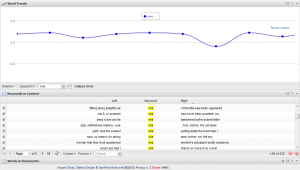

TAPoR

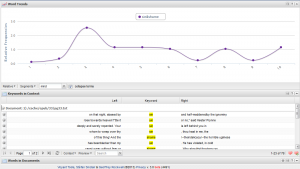

Trying out HyperPo and experimenting with different combinations of words was worthwhile. After fading through the first page of largely uninteresting words, I came across the word “One” once again. Equipped with this new tool, I decided to map out its presence throughout the text and perhaps account for it.

Yes, “One” is a common word and could have little significance. It could also be a particular vocabulary quirk of Hawthorne (or perhaps the era in which the book was written) to use “one” rather than “you” or “she” or “he,” or to refer back to a person. Certainly, this is the case. But there are numerous instances in which “One” serves a more interesting purpose. In sentences like “. . . deep a dye as the one betokened by the scarlet letter,” one is used to emphasize the unique suffering of Hester’s situation. Again, more likely Hawthorne uses “One” incidentally as part of his diction, but cases like these suggest the possibility of something more.

Next I decided to experiment with a more concrete idea. I selected “child” and “infant,” both of which refer to the character Pearl in the novel, and attempted to set them against each other on the graph. This did not work for some reason, so I was forced to look at them separately. As expected, “Infant” occurs almost entirely on the left side of the graph, the beginning of the novel, when Pearl is, well, and infant. Child, meanwhile, appears steadily throughout the novel, starting just after “infant” ends (with some overlap), as well as a slight dip in the set of chapters in which Pearl does not appear. This looks good. Despite the minor technical hiccup, HyperPo seems to be doing its job. Of course, in this case, I only set it to tell me something I already know, suggesting that I may not be asking the right questions. But this was an short experiment with the capabilities of the tool itself, so I have no choice but to forgive myself.

As one final experiment, I noticed that HyperPo allows you to collapse different words and view their frequency as one unit. I tried this with “sin” and “shame,” words associated with Hester’s scarlet letter:

As you can see, the greatest frequency of these words together occurs toward the beginning of the novel, while it fluctuates up and down before going up near the end. What can we determine from this graph alone? Perhaps the scarlet letter torments Hester most toward the beginning of the novel, during Pearl’s infancy. The passage at the end is also notable for the line,

. . . long since recognised the impossibility that any mission of divine and mysterious truth should be confided to a woman stained with sin, bowed down with shame, or even burdened with a life-long sorrow.

Focusing on these central themes at the end accounts for the tiny spike. Of course, I can verify none of this without directly consulting the novel, which further indicates the use of this tool as a form of provocation, a way of reshuffling the words of the text to raise interesting questions. In this sense, to “see through the text” involves a specific mapping which requires zeroing in specifically on finite sets of words. The experience of HyperPo is like reading a text with a powerful, magical magnifying glass that guides the reader to common and specific parts of the text. Okay, that analogy may not work as well as I was hoping, but I gave it a shot.

Conclusions

Overall, HyperPo is a robust tool that has a lot to offer, and I have of course only scratched the surface. Wordle and WordItOut are useful for expressing a main idea or message easily and succinctly, but I imagine HyperPo could be used for more serious research.

This exercise has taught me that one must be deliberate and careful while using these tools, provided that you want to come out with something useful. They can be used to confirm what you already know, which most would argue is quite boring. It takes a great deal of time and experimentation before coming out with a truly stunning result, and these are the ones that are the most worthwhile. These are the moments when you are able to look at a text in a new way, and this alone justifies the use of these tools.

In this sense, Ramsay’s these tools indeed create a sense of the “estrangement and defamiliarization of textuality” by forcing the reader to view a text in an entirely different way. For all of its simplicity, Wordle’s ability to recognize and display common words presents the text in its most basic form. No, this is not the same as reading The Scarlet Letter. Not even close. But as a tool of provocation, the re-shuffling and re-oganization of words could lead to new insights about the text. Perhaps HyperPo best demonstrates the capabilities of these sorts of tools for scholarship. I’m still not convinced that any of these tools can help us “Read a Million Books,” as they require the user to be familiar with the texts beforehand in order to glean useful information, but perhaps that is a topic for another day.

The Scarlet Ebook

I selected Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter for three not so exciting reasons. 1. I have the book on hand. 2. Nearly all of the books I am interested in or enjoy come after the public domain works. 3. I happen to enjoy this one.

With that out of the way, The Scarlet Letter is available on all four resources: Project Gutenberg, the Internet Archive, HATHITrust, and Google Books. Let us go down the list and see what we have here.

Project Gutenberg is available in a variety of formats: HTML, EPUB (no images), Kindle, Plucker, QiOO Mobile, and Plain Text UTF8. It isn’t clear what edition of the text the HTML version is based on, only that this version of the ebook was first released in 1992, produced by Dartmouth College, but has been updated in 2005. The HTML version contains all of the materials you might find in a print version of the book, such as biographical information, a list of works, and an editor’s note, but as this is HTML, there was no effort here either for the text itself to resemble a printed book, or to take advantage of some of the possibilities of the ebook format.

A few of the other formats seem unfamiliar to me, and others require programs or e-readers to view. Alas, being a non-Kindle user, I moved on to the online reader, which divides the novel into pages, serving as an alternative to scrolling through the text. But the online reader does little else to mediate or alter the text.

The Internet Archive provides what appears to be three versions of the manuscript, but on closer inspection they are all identical copies of the HTML format of The Scarlet Letter taken directly from Project Gutenberg. The site provides a space for reviews (presumably for opinions on the quality of the e-copy or perhaps even the novel itself). It is also interesting to know that the novel has been downloaded 1,848 times.

Typing The Scarlet Letter into the search bar of HATHITrust yielded 931,602 results. Woah. Could I narrow this down? I clicked the option for “full text only,” and with my results narrowed, I happily clicked the search button only to be bombarded by 480,863 results. Hm. What if I clicked “Nathanial Hawthorne” as the author. That brought me down to 720 results. Perhaps my search was still off, but I decided that this was the best I was going to get.

I apologize for not having mustered the time or the patience to search through 720 results, although I suspected that the correct items would be found on the first page. First, a word on the functions of the site: HATHITrust provides a few limited options of viewing the text, but these only amount to zooming and flipping pages (or scrolling). The search function is quite nice and works well, although any Word or PDF file has this capability.

Going right down the list, the first selection brought me to a scanned copy of the 1889 Boston Houghton, Mifflin and Company version of the text, featuring black splotches and lines, and even a Due Date card in the back. In all other respects, however, this appeared to be a fairly well-done copy, and I would rather download a PDF of something that resembles a book rather than an HTML version that appears like a poorly designed web page.

How did the other copies fair? Well, it turns out many of them were duplicates, but one version caught my eye: The Scarlet Letter “with illustrations of the author, his environment and the setting of the book; together with a foreword and descriptive captions by Basil Davenport,” published in 1948. And the illustration? Well, it scanned quite well, I suppose. Hawthrorne does sport his mustache with pride.

Finding most of the copies of HATHITrust in respectable shape, I moved on to the last resource: Google Books. Having already sorted through Project Gutenberg’s wide variety of formats, The Internet Archive’s borrowing the most simplistic format (HTML) from Project Gutenberg, and HATHITrust’s large quantity of nearly identical copies (available for download as PDFs), I was ready for whatever Google Books had in store.

Typing “The Scarlet Letter by Nathanial Hawthorne” of course yielded many, many results, but I could see right away that only one was an actual copy of the text. Here I found a scanned copy of the text from the 1898 Doubleday and McClure Co. edition. And yes, this one also features a stunning illustration of Nathanial Hawthorne and his mustache. Google Books gives you the option to download the book in Plain Text, PDF, and EPUB formats. The quality of the copy itself is quite good, from what I can tell. But more importantly, Google placed some effort in supporting some unique features. In addition to the search function, clicking a chapter title in the table of contents will bring you to the correct page. This is a long ways from a hypertext version of the novel, but Google certainly took a step in the right direction.

Ultimately, I was not overly impressed with any version of the text, although I did not experience any of the extreme formatting issues Duguid encountered while researching Tristan Shandy. Moreover, as all copies are free to use for whatever purposes you may desire, I suppose I shouldn’t be one to complain. Google Books provided the most impressive copy of the text, even though I would still prefer my own hard copy of the novel next to a scanned e-copy with a search function. I consider my $4 well spent. I can imagine a more robust hypertext version of The Scarlet Letter, but perhaps that is a blog post for another day.

Definitions and Boundaries

I suppose introductions are in order. My name is Dan, and I’m a second year MA/PhD English student at Maryland. Why am I in this class? Well, I took Neil’s Technoromanticism course last year, where I got a taste of what DH is all about. For my final project, my partner and I worked with Woodchipper, a topic modeling tool. Together we compiled 100 or so science fiction texts, threw them into Woodchipper (well, Travis did that part for us), compiled the results, and each wrote a paper on our findings. I tried to locate certain commonalities between these texts, as I was interested in seeing if Woodchipper could determine subgenres and common topics. This experiment was rewarding, novel, and a lot of fun, and, well, now I’m here.

On to the readings! The biggest question has been, “What is and what isn’t DH?” Others have already interrogated this question, but to add my voice to the masses, the core of this question seems to arise from the deliberately open-ended nature of DH itself. Is it a field or a method? Is it about making or interpreting? The consensus on these questions is that there can never be a consensus. By seeking to define itself as broadly as possible—interdisciplinary, collaborative, a methodology and a field, theoretical and post-theoretical—Digital Humanities wants it all. This is a productive and ambitious outlook, perhaps utopian, and certainly tactical. After all, why should a new field set out to place limits on itself? This strategy is especially true here, as the strength and foundation of DH lies in its eschewing categories and traditional ways of thinking.

Despite this, there is a still tension surrounding the question of what is and what isn’t DH. As Ryan Cordell mentions in the Twitter Storify,

“I do actually think we need at some level to distinguish what is & isn’t DH-otherwise why call it a field at all?”

Therein lies the central conflict of this debate. How long can we consider DH both a field and a methodology? Certainly, when the dust settles, DH will have no choice but to establish itself more clearly, despite its open-ended nature. For better or worse, this will mean acknowledging its boundaries, perhaps not by deliberately setting up or establishing them, as that would conflict with its ideology, but by necessity a field must contain boundaries or it cannot be considered a field at all.

On the other end, we have the argument that DH is only a methodology. If this is the case, we can say, “To heck with restrictions!” Golumbia recognizes these two differing definitions of DH, one narrow and the other expansive, and one a field or discipline and the other a methodology and a tool. In the comments, Ted Underwood writes,

“Part of the reason why I’m not troubled by terminology is that I don’t think we’re going to come out of this with a distinct field at all. I suspect the boundaries of existing disciplines will hold, and DH will end up as a loose name for an assortment of different interdisciplinary projects.”

So which is it? It is tempting to say that DH is both a field and a methodology, and this answer might be closest to the truth, but as DH matures, it will inevitably have to define itself more clearly and recognize its boundaries. For now, the open-ended, expansive definition of DH is useful for attracting attention to the field, and it will be interesting to see how its definition grows alongside Digital Humanities itself.