I selected a group of short stories by Edgar Allan Poe for this exercise. It was difficult to work with Machado de Assis this time, because I did not find the translation into English. Also, I was curious about seeing the particular voice of Poe’s stories, its peculiar vocabulary. But I also thought that it would be interesting to see some translation phenomena at the same time. I selected the anthology that Charles Baudelaire translated by the title Histoires extraordinaires. As I could find this edition in Project Gutenberg as well as the complete stories by Edgar Alan Poe, I decided to create a document in English with the same short stories.

It is well known that Baudelaire was the first translator of Poe into French and that this translation was very important for European literature. I wanted to see what happened if I compared the two anthologies through Wordle and WordItOut, and then HyperPo. So I began my exercise with some extra questions: Could we get interesting or relevant information about the words that appeared in the original and the translation? Are those programs helpful tools for Translation Studies?

I began with the Google Ngram Viewer, to compare Poe and Baudelaire in their respective languages, with pretty obvious results (I must admit I spent some time playing battles between couples like Derrida/Deleuze; Godard/Truffaut, etc. with amazing results):

But I wanted to see what happened in Spanish, and the results were more interesting. They are published or are subject of analysis almost at the same time! Why did this happen? Is the reception of Poe similar to Baudelaire’s in the Spanish speaking world? Are their figures similar?

When I created a word cloud through WordItOut I realized that there was a list of common words that the cloud ignored, and that I could change that list as well as replace characters. Also, I could change a lot of settings as number of words, order, color, etc. But when I tried to create a word cloud with the French version, I did not have the option of a foreign language, so I did it myself, adding the most common French words to be ignored by the cloud. The result was this:

I was surprised that most of the words were very common words, so I wonder if analyzing these results could be interesting. The importance of the word “now” maybe is telling us something about Poe’s short stories style regarding the treatment of time. We can make multiple interpretations from this result: the question of “time” in Poe’s literature, or moreover, the question of “time” in Baudelaire’s literature. Why Baudelaire chose these and not other stories to his first anthology of Poe’s work? Is there something behind the words?

When I used Wordle, I realized that the list of ignored words is not so big. Some common words entered in the word cloud. I noticed that this program had a filter for different languages, but it happened the same with the French version, as I could see many words of common usage, as “bien” or “cette” or “comme”. So, in that case, Wordle was less useful to find meaningful results.

We have to think on one important issue: that we have to customize very carefully these tools. That arises the following questions: Are we making a text say what we want it to say? Is it just another way to do the same as the kind of literary criticism we already have?

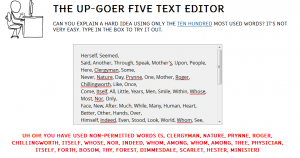

When I pasted the words from WorditOut to Up-Goer, the program permitted all of them except six: “Dupin”, for it is a surname, “indeed”, “balloon”, “manner”, “itself” and “earth”. I found it interesting that most of Poe’s words were common.

Using CLAWS, I found that most of the words are nouns, (I used the help of Wordle to see this in a clearer way!), adverbs, adjectives, general determiners, the “base forms” of the verb “to be”, prepositions, etc. I think it is an interesting tool when you are looking for something very specific. Again, all depends on the questions you have, the relevance of those questions and the relevance of the results. Data just for the data is meaningless.

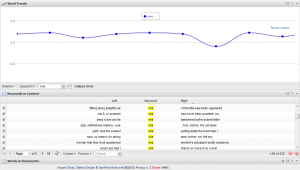

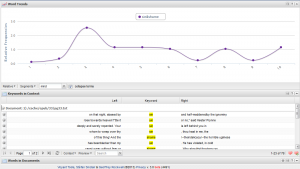

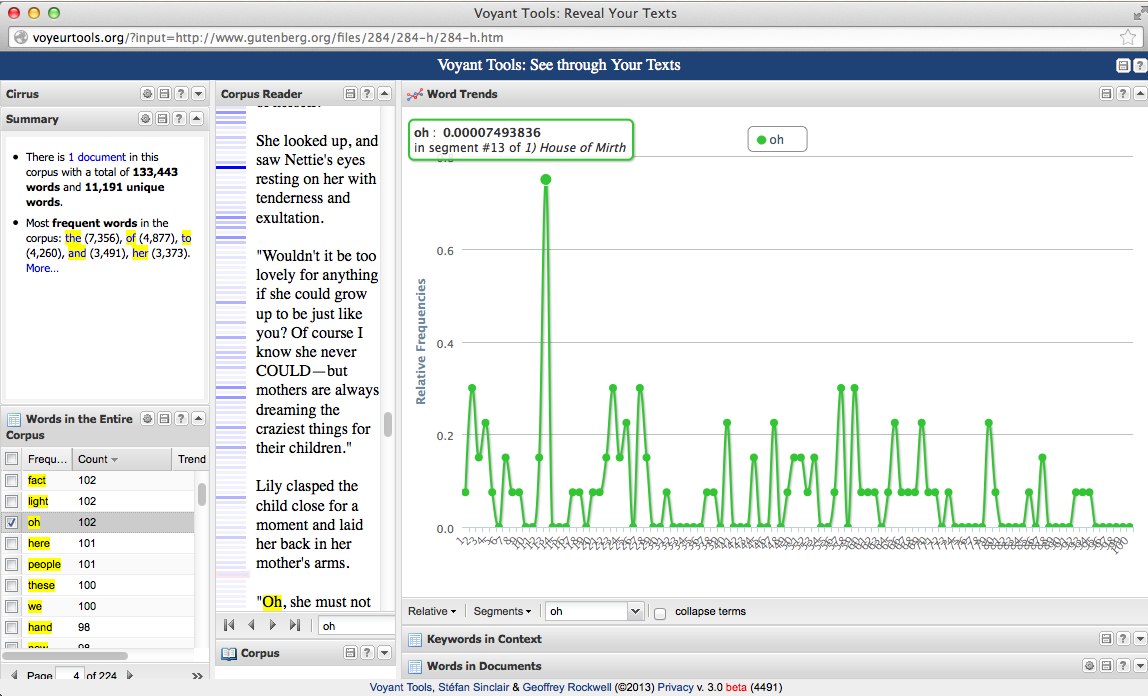

Finally, TaPor is a very interesting program. It is much more sophisticated and useful than the word cloud creators. It works with texts in French, Spanish, German. The “voyant tools” were interesting, like seeing the frequency of certain word(s) in a graphic, in context, etc. You actually can “see through your texts” as the Web page invite the users. I found that “death” and “idea” appears the same amount of times! And “great” and “little” are the most common used adjectives. It is also interesting to see the differences between the two languages. The results tell us a lot about the particularities of both languages, like the common use of the verb “to say” in English language literature opposed to the use of synonyms of that verb in other languages’ literatures, as it is more frequent in the English version that in French version. There are a lot of data to read and analyze here!

I think all these tools are useful for translators to understand some phenomena, how we translate, how some writers and some translators use a particular vocabulary, style, phrase construction, etc. I think it would be great to do that with an own translation and see the results, and also to compare two translations of the same work!

Conclusions

At this level (just trying new tools, not researching for any particular paper) I found curious numbers and graphs, but if I had had in mind a set of questions and hypothesis, it would have been very useful –but always depending on the relevance of the questions and responses. I think that if we have questions very well defined, there will be some interesting results. (I wonder about the difference between answers and results. Do computers answer or just give us results?) And once we have some answers from the computer, we can reformulate new questions, which is the most interesting part of literary criticism, activity that, as Ramsay says, did not change with the introduction of computers. We interpret the results that machine can give to a certain research –word frequency through a book, through time, etc. As Ramsay affirms,

“If something is known from a word-frequency list or a data visualization, it is undoubtedly a function of our desire to make sense of what has been presented. We fill the gaps, resolve contradictions, and, above all, generate additional narratives in the form of declarative realizations.”(62)

Results are results and they can not be changed; they are a fact. But we read them and we arrive to different conclusions, even though we have the same object in front of our eyes: algorithms, data or a book. Those are just different ways that let us read a story, and reading through machines is a fascinating one that many times defy our preconceived ideas or give us new perspectives of reading it. That feeling of learning to read again, of seeing a text in a whole different way, that “ostranenie”, are fundamental to begin making questions, to try to find new paths to fight against common places in literary criticism. Also it is a way to do things with books: like snipping its pages. That is something we can do because we are working with digital texts. And digital texts have a very different substance than printed texts. With computers we can analyze just text, but not other important details that also make part of our reading of a book (and the readings that that book had in the history of our culture) as the book itself: how and where it was published, how its covers are, from which collection, etc. So not everything can be read through machines, and we have to pay attention not to isolate the “text”, as if everything that should be read is just in the (digital) words of a text.

Through my experience working with different programs for this exercise, I realized that I was finding new questions (everything was questions! and I could not arrive to any answer at this level); I also found new ways of thinking texts, of thinking translations, and that is what I really like to do as a reader and as a student.