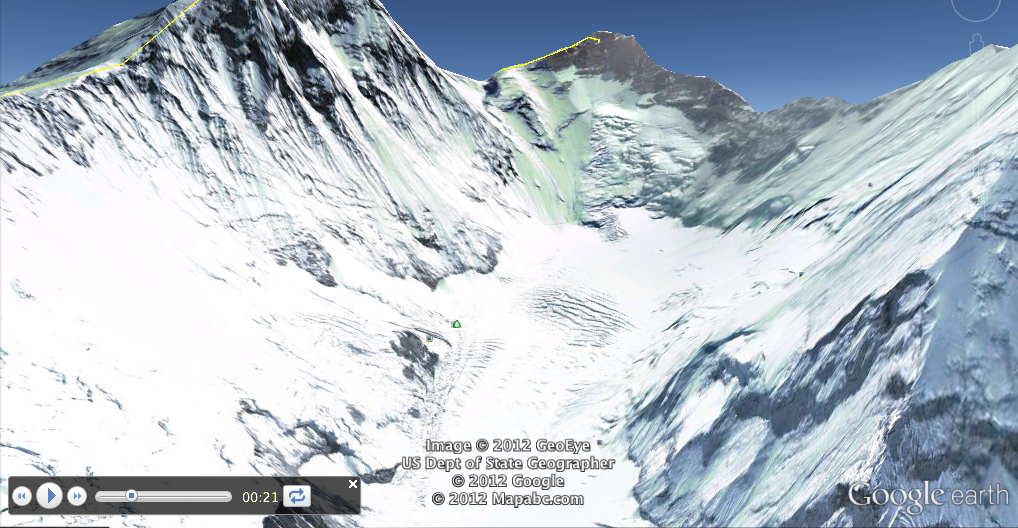

It’s a bird’s eye view of mountains, each dotted with a spot of pure whiteness, patched with limestone-green tints that glisten softly. There must be hundreds of them down there, each in a natural tandem. They mold into one another effortlessly, transitioning from snow-capped peak to snow-capped peak. They know each other well.

The mountains know they don’t have to try; their beauty is obvious. As Google Earth’s tour pans up the mountain’s central snow-filled crevice, two steep and jagged walls greet our peripherals. They are stoic, just as the rest of their mountain counterparts, but with an ego: they know they make up the tallest peak, the Mount Everest itself.

They’re so high that they’re snow-filled and pierce the static blue sky. These mountainous walls seem to whisper, “Try me.”

The peak jumps forward on my screen. The look is exhilarating; it’s one that few have seen live. Just scores of jagged, breathtaking structures, nature’s skyscrapers. It overlooks eons and scores and galaxies of mountains, mountains of the small variety and the tall variety that have stitched centuries of human awe and confusion, mountains as jagged and diverse and glorious as the human race.

A pan out, as I scroll with my mouse and occasionally tap my arrow keys to reach maximum height. A feeling of insignificance hits me after noting the rolling field of mountains on my laptop’s computer, their extension into everything as far as the eye can see. I’m small. They’re large, larger in size than the 10 most powerful people running our world. How does that work? Isn’t bigger supposed to be better? Nothing makes sense when you take a look at the land’s vastness, a superiority unseen by most of the world.

I pan upwards and a blob of white-green-purple-black splashes in front of my eyes. It’s steep and continues to make me feel miniscule. I hit the top. A surprising feeling of satisfaction washes over me. Though I did no such thing, I feel as if I climbed a little bit of it. I saw the top of Everest; I saw the precision, the white-spotted beauty of the most famous mountain in the world.

And while the interface makes you feel like you’re there – in the crevices, on the peaks – I’d argue that it doesn’t feel inherently beautiful. That beauty lies in the hundreds of photos in icons lining Google Earth Everest. After all, Google Earth is a 3D map at heart. A map will show the precise details but isn’t meant to evoke beauty as a photo would – it has logistical aesthetics and simulates beauty, but does not have aesthetic values of beauty inherent to a natural wonder, such as quality of light, clouds, live details. I feel every part of the Everest experience – the idea of being small, awe at details of the structure, exhilaration at the peak – but I’m not struck by beauty when panning the area.

Compared to text virtualizations, Google Earth is very helpful in visualizing the space, its purpose and (most importantly) the feeling that runs through us when we see a site. Words can describe a space – just as I’m doing here – but when you really want to see a space, words cannot match up to the jaw-dropping force of images. For example, when I say “the mountaintop seemed to rise, its white-topped glory dominating the other babies in its midst,” you can visualize it, but Google Earth’s interactive 3D maps help you to feel it, too. Though I can’t see the exact way snow is falling on a mountain, I can understand the power of the space and why we’re drawn to it through elements of height and the panning features.

Nice work, Beena. I particularly enjoyed your last two paragraphs where you thought carefully about how the digital interface compares with text, being in a space physically, and photographs.