Alright, it is time for a super geeky confession: I belong to a Sherlock Holmes society. At the last meeting a number asked me what I was studying and I tried to explain Digital Humanities to them. It wasn’t, shall we say, the greatest success. So I’ve been thinking, at one of our next meetings maybe I’ll finally give the presentation–a duty I’ve shirked for all of the 10 years I’ve belonged to the club. I was trying to think of ways to blend DH with Sherlock Holmes and show how even the most basic of DH tools might be useful when understanding the Sherlock Holmes stories.

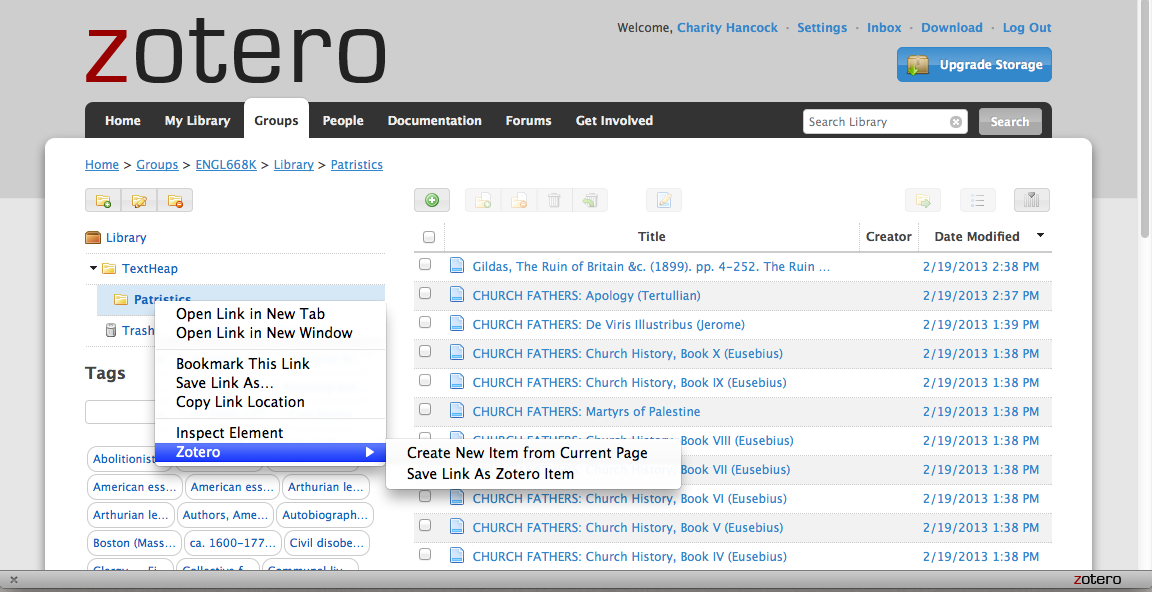

Well, the work for this coming week to find a library of sorts related to our texts started me thinking about the similarities between Dracula and Sherlock Holmes–and the men responsible for their creation. Both authors considered themselves to be the epitome of the Victorian gentleman–upholding the beliefs fundamental to that image. As such, wouldn’t they have a tendency to choose from the same offerings of the LDA Buffet? Some additions of Dracula, such as my Project Gutenberg copy, even bill it as “A Mystery Story.” Would the two men’s word choice reflect this similarity in experience and ideal?

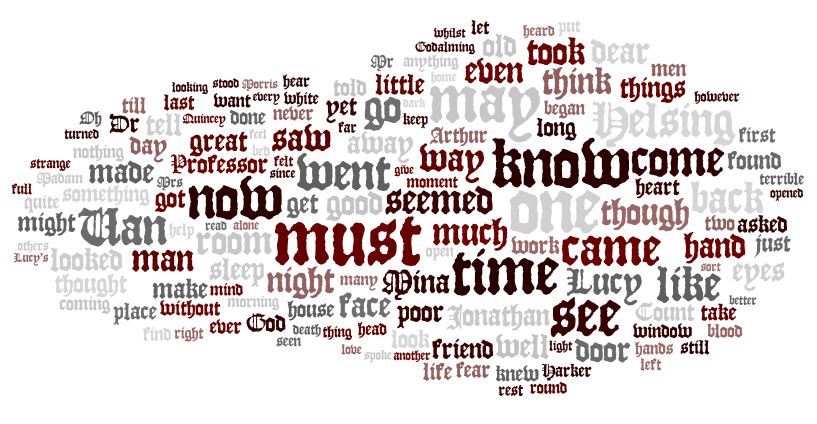

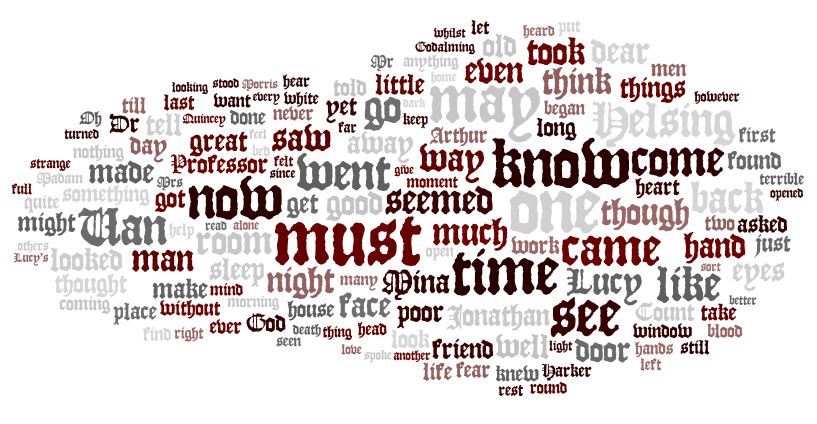

I tried doing the Holmes word cloud with one text–Hound of the Baskervilles–but the names like Baskerville and Henry started to dominate so much so that one couldn’t see much of the other language, so to balance it out I stuck as much of the Sherlockian Canon as I could find into Wordle the resulting “footprint,” if I may so call it, seems more representative of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s writing as was the goal. And judging by the results, it would seem that the two do share a similarity in word choice. Words like “man,” “know,” “must,” “may,” “light,” “night,” and so on all have strong followings in the clouds.

Now, I’ve often heard said of Doyle that he was not a terribly good writer and that he, instead, had the good fortune to create a character who was original and fascinating enough to come to life in spite of this less than fortuitous entrance into the world. Holmes captured the imagination of the readers in spite of Doyle’s talent rather than because of it. Could the same be true of Dracula seeing the linguistic similarities between their authors? I’m not entirely sure how to test this particular theory–maybe someone else will be able to suggest one–but I thought I could test how the popularity of the characters of Dracula and Holmes have compared to that of their creators. The idea being that if Holmes and Dracula and their creators shared the limelight it would suggest that there was as much to be said about the creation as the creator. Doyle and Stoker would be as interesting as authors as their creations were as literary characters. The result is as follows:

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

Now, the one problem with the above, is that it doesn’t take into consideration that Darcy is rarely called by his full name and has a very common one, at that, unlike Holmes and Dracula. So, here is the above result modified with the revision of “Mr. Darcy” rather than simply “Darcy.” It is not ideal, how often does, when writing about Austen’s ideal man, so formally refer to him as “Mr. Darcy.” But, one should at least be able to mentally average the two results to attain some sense of our Darcy’s popularity in English writing:

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.

Further, this research suggests that Stoker and Dracula shared a similar relationship with their fictional creations and made similar word choices. We can’t definitively prove that Stoker and Doyle were particularly terrible writers, but the results suggest that other writers do not stand in the shadows while their creations take the limelight as these two do.

As a final note: the class discussion of anime reminded me of a statistic I read long ago that stated that there were more Sherlock Holmes societies in Japan than their were in the UK. As it turns out, according to the list of active Sherlockian societies kept by Peter E. Blau (a member of the Baker Street Irregulars, the most illustrious Sherlockian society), Japan has 15 societies while the UK has 16. Still, the figure is impressive and made me curious how Holmes’ popularity (and Dracula’s) compared by geographical region and language. Alas, I don’t know how to translate Holmes into Japanese or Russian (there is a large following there as well) so I’m limited to American and British English for Google’s Ngram Viewer. However, the results were still fascinating:

I find it fascinating that to the Americans, Holmes’s popularity grew far more rapidly than in England, yet once again, the vampire steals the show.

It would seem that while Holmes was very popular in the UK since his creation, Dracula has recently stolen center stage–in spite of all the latest Sherlock re-imaginings.

In conclusion, I think Holmes would have been a DHer. The man who cried, “Data! Data! Data! [....] I can’t make bricks without clay,” would have appreciated the way in which DH offers one tremendous information at one’s fingertips and the tools to make sense of it. Holmes would especially have to appreciate the fact that the methods of the Digital Humanities could be used to catch our own Napoleon of Crime, so to speak, Osama bin Laden. And as for Dracula? Well, clearly DH has brought him out into the light of day.

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.