(I steal “computer-enabled play” from Irizarry, quoted by Ramsay on pg. 36 of Reading Machines).

The reason I was drawn to include the phrase “computer-enabled play” in my title was because that is really what I felt like I was doing throughout the exercise: playing, fiddling, fooling around, testing out, exploring, etc. Similar to what Mary expressed, I found that some of these experiments were overwhelming (or annoying) in their unfamiliarity, but I soon discovered that if I “played” with the tool enough, I could eventually gain some insights into The Marble Faun in a new way (i.e., different insights than I would have garnered from reading the text in a traditional manner).

Wordle and WordItOut seemed especially “playful” with their fun names, bright colors and graphic visualization. As I’ll probably reiterate several times in this post, these tools did require some “fiddling,” though.

WordItOut

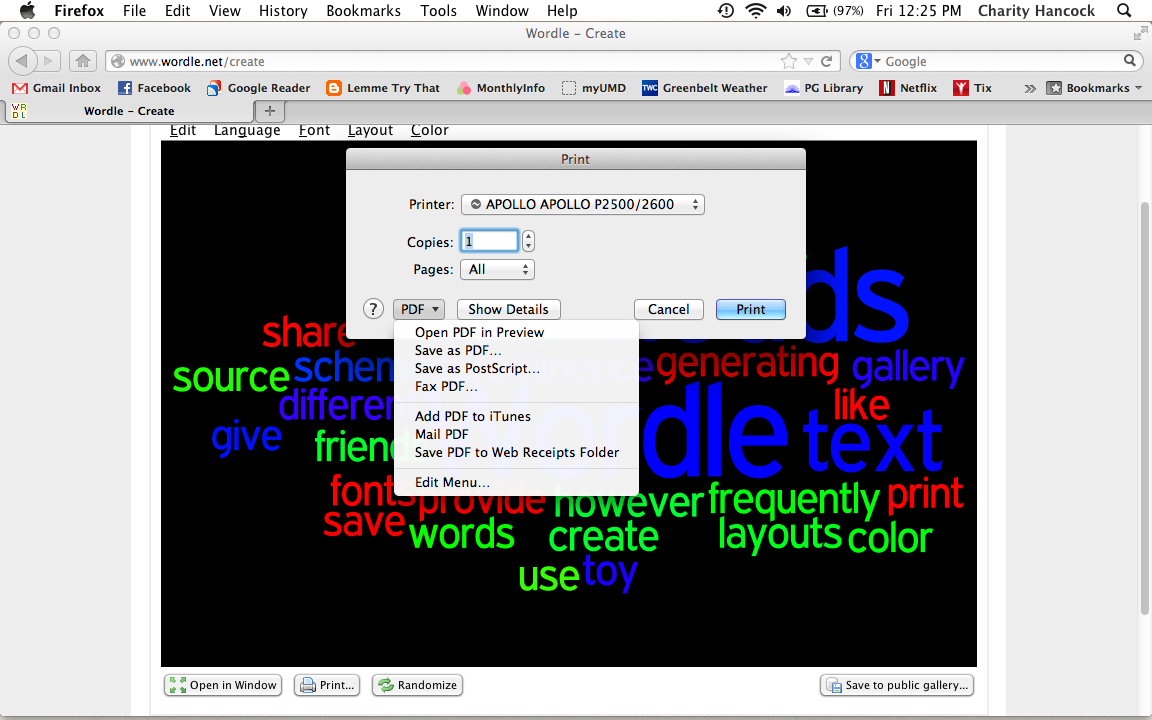

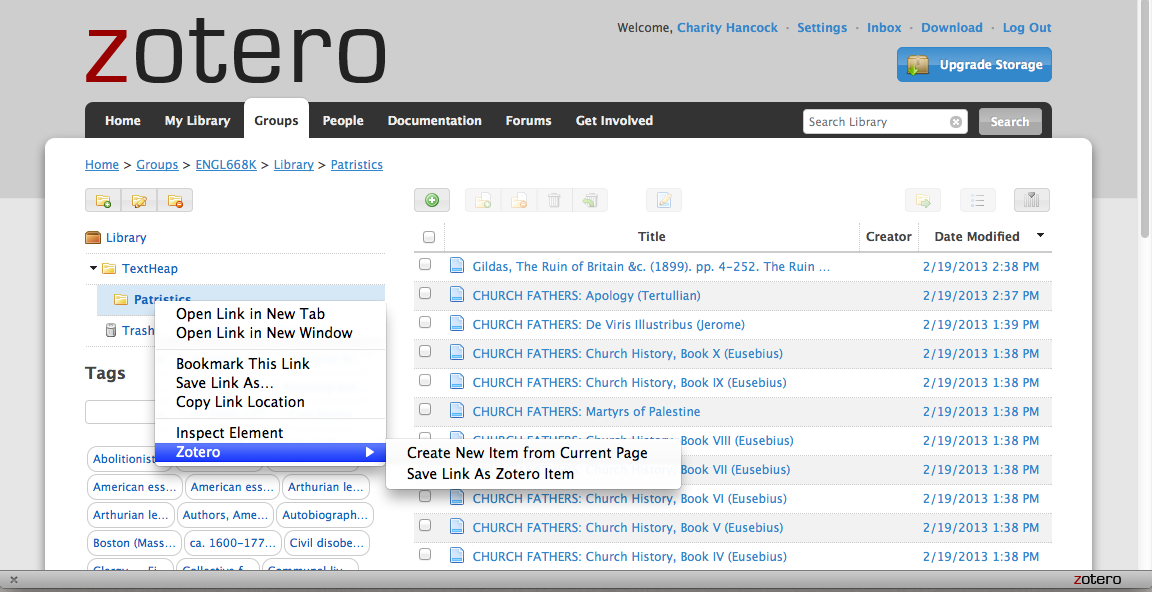

Wordle

For both tools, I used the full text of The Marble Faun, from the Project Gutenburg plain text online version. With WordItOut, I appreciated the function to tweak the list that was generated. I could view the list in ascending count order, alphabetically or randomly (though I’m not sure how the last two would aid in a critical analysis). I was able to increase or decrease the number of words. Also, unlike Wordle, WordItOut allows you to see the generated word list in both list and visualization form, which was helpful when I wanted to copy the list for further exercises.

As others have observed, with narrative forms (novels), it seems that names and other pronouns seem to be most prominent. In a story like The Marble Faun, it was actually interesting to see which character was the most represented: Miriam. (The Marble Faun is sort of like modern day sitcoms that center on a group of friends–so imagine that we Wordled an episode of “Friends” and discovered that “Rachel” is the largest name–what does this tell us about the group dynamic?). In The Marble Faun, the drama centers on MIRIAM. I thought it was interesting that Hilda is the second largest name–so in a novel which actually has fewer female characters than male, the females still win out in nominal presence.

Other prominent words seemed to thematically center on art (not surprising; the characters are artists living in Rome) and time (not surprising; Hawthorne often focuses on the interplay of past, present and future reality). Wordle and WordItOut thus demonstrated for me the point Ramsay notes more than once, that at a base level, digital tools might merely confirm analyses we have already made.

Up-Goer 5

After struggling with the “define digital humanities” Up-Goer 5 challenge before beginning the exercise (how unnatural for literary scholars to prioritize simple, oft-used words over our sophisticated vocabularies!) it was interesting to use the tool to investigate a pre-generated text. I used my list from WordItOut, but removed the names as I didn’t think they would propagate any new insights (i.e., it would be no surprise that “Hilda” is not in the top 1000 used words). What I did find, though, WAS intriguing.

Of 97 words produced by WordItOut as “most used” in The Marble Faun, only eleven did not make the Up-Goer 5 top 1000 word list. These were: sculptor, Rome, marble, among, itself, whom, Roman, nor, poor, tower, and indeed. I’m guessing that Rome and Roman are too specific (proper nouns) to merit top-1000 usage, while sculptor and marble as nouns also seem too obscure (we don’t talk about sculpture very generally or often). Nor, whom and indeed are rather sophisticated uses of grammar, so their absence doesn’t surprise me. I don’t have an explanation for among, itself, poor, or tower—any thoughts?

What’s left behind (in the top 1000) is interesting when you consider the words as “topics” of interest (in the sense that oft-used words might represent broader themes): life, heart, friend, good, human, world, love, art, idea, moment. Not only are they huge topics in Hawthorne’s text, but also, apparently, in everyday speech.

CLAWS

On to CLAWS, the realm of tagging. This, I did not find playful. I was rather confused, though finding the accompanying “tagset” key was somewhat illuminating. I didn’t have the patience to count the different types of word forms, but that could have been interesting to see–were Hawthorne’s 100 most-used words from The Marble Faun mostly pronouns? (probably). Singular nouns? Comparative adjectives? Etc. etc. So I can see how CLAWS could be a useful tool, but I didn’t like the aesthetic of the list that was generated (no spacing, no counting) so, admittedly, I moved on.

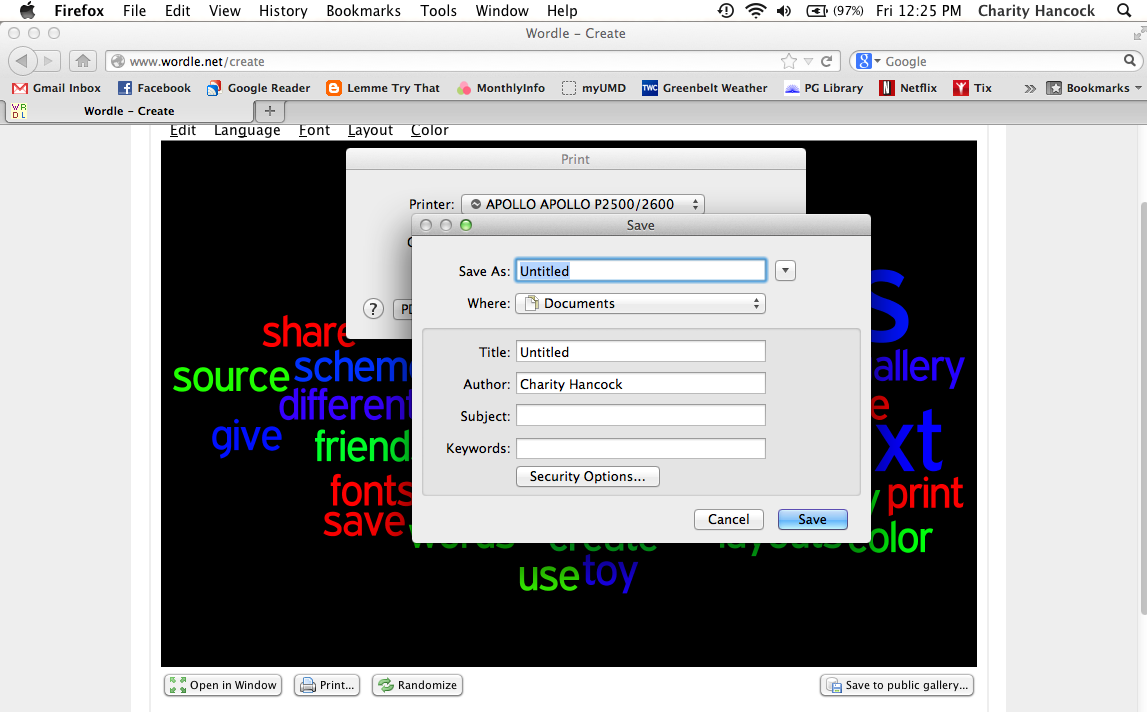

TAPoR

TAPoR, while also intimidating with its unfamiliar interface, was “playful” in its potential for “fiddling,” as I previously described. The more I played around with it, the more I found ways to make it work for me. After scrolling through the word lists in the lower left-hand corner (sorted Frequency vs. Count vs. Trends) I clicked on “heart” to see what came up.

I don’t really understand the graph in the upper-right hand corner, though I know you can view two words at once to—I presume—compare frequency at various points in the book. For instance, I viewed “woman” and “sympathy” together and saw a very similar pattern, suggesting that woman & sympathy are often discussed in tandem. This is not surprising, given that Hawthorne’s romance could really be considered a sentimental novel and he’s constantly talking about the female characters’ womanhood and capacities for sympathy (e.g. Hilda is very sympathetic, Miriam not so much). What confused me were the “segments,” though I suppose you could generate the graph so that it represented chapters, if you knew how to finagle that breakdown. That way, you could see where, in the novel, topics were discussed with higher frequencies. “Heart,” for instance, skyrockets at the end of The Marble Faun, according to this “Word Trends” graph.

I also got the hang of the concordances tab and found these lists extremely interesting. Under “heart,” I could observe the following concordances:

Intimate/heart/knowledge

Hilda/heart/life

close/heart/beautiful

brain/heart/think

trust/heart/trusts

secret/heart/burns

These are only a few examples (from 89 instances of heart in the first volume of the novel) but SO INTERESTING! I’m especially intrigued by instances like “knowledge,” “brain” and “think” surrounding the presence of the heart, since we get that tension between cognition and emotion there. Trust and secrets regarding the heart don’t surprise me at all given the nature of the novel, nor does the presence of the “beautiful.” Hilda’s concordance is also not surprising—the trio of “Hilda,” “heart” and “life” is only too perfect. (I know I’m not being very clearly critical here, but I’m sure you can see the potential for developed analytical writing on these topics).

One question I had while using TAPoR concordances: TAPoR doesn’t select the immediate surrounding words, but rather “keywords.” For instance, “secret/heart/burns” comes from the sentence: “There is a secret in my heart that burns me!—that tortures me!” This is a pretty good example—we presumably don’t care about “in,” “my” or “that,” but how are the keywords chosen? Does the software just eliminate prepositions? Do we lose the presence of “torture” here? Compare to an example like “only/heart/sought.” The sentence from which this concordance is generated is, “But if it were only a pent-up heart that sought an outlet?” To me, “pent-up” seems important, while “sought” and “outlet” are equally important. So, I’m just wondering (and perhaps someone can actually tell me) how the concordances work—how are the surrounding terms generated?

I could really see myself using TAPoR in the future (though, again, the interface doesn’t really appeal to me and I wished I could have enlarged everything–but these are minor complaints of a whiny variety). As someone who was widely unexposed to DH tools before this class, Ramsay’s Reading Machines and our exercises have legitimately moved me “Towards An Algorithmic Criticism.” The text, in its descriptions, examples and analysis of digital tools and their impact on/interaction with literary criticism was seriously illuminating. We were prompted to consider how

“the effect is not the immediate apprehension of knowledge, but instead what the Russian Formalists called ostranenie—the estrangement and defamiliarization of textuality” (3)

regarding our experience with the various digital tools today, and it certainly applies. “Estrangement” and “defamiliarization” certainly describe my “computer-enabled play” with The Marble Faun today. We are distanced from the text when the computer intervenes, transforming prose into lists, visual graphics, concordances, and line graphs. BUT this does offer, though not immediate, new “apprehension of knowledge,” I believe. From reading Hawthorne’s prose, I do not “know” whose name appears most often in the text, even if I can guess. Conjecture becomes fact, and fact leads us to points of inquiry, new questions regarding “why?” More articulately put by Ramsay on pg. 62:

“If something is known from a word-frequency list or a data visualization, it is undoubtedly a function of our desire to make sense of what has been presented. We fill in gaps, make connections backward and forward, explain inconsistencies, resolve contradictions, and, above all, generate additional narratives int he form of declarative realizations.”

I’d like to point out a couple of other passages which stuck out to me and helped me frame algorithmic criticism this week:

“The computer revolutionizes, not because it proposes an alternative to the basic hermeneutical procedure, but because it reimagines that procedure at new scales, with new speeds, and among new sets of conditions” (31).

“Rather than hindering the process of critical engagement, this relentless exactitude produces a critical self-consciousness that is difficult to achieve otherwise” (34).

And, to end, perhaps a point that generates and necessitates discussion: in opposition to “ambiguity,” the computer “demands an answer” (67). Is this a limitation? Shouldn’t there be room for ambiguity in literature, even if it doesn’t fit into an automated output? Ramsay continues, “…the computer demands abstraction and encapsulation of its components” (67). Again–is a limitation present, here? Are all texts (/words/phrases/data sets) discrete, with potential to be “encapsulated?” Does the computer miss something the subjective mind would not?

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

Google’s Ngram Viewer would seem to support this theory. The characters have survived far better than their creators–in fact, Holmes leaps to the forefront from the instant of his creation (Dracula has a bit more of an uphill battle at first). But maybe this is to be expected? Do characters always do better than their creators? If so, let’s test on an undeniably talented author and their beloved creation, Jane Austen and Darcy:

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.

So clearly, this is not true among all authors and their creations. Austen gives Darcy a run for his money. Now, one must also take into account that Austen published far more texts than Stoker or Doyle. Her’s were also far more popular–anyone heard of or remember The White Company? No? That suggests to me that Doyle’s talent with the written word is not as strong Holmes’s persistance in the memory.