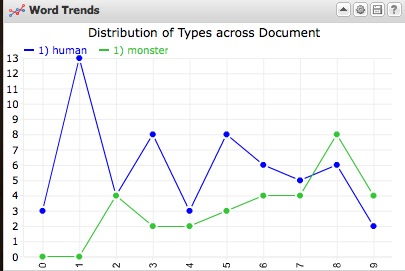

For our group teaching tomorrow, Kristin Gray, Kathryn Skutlin, and I will begin class by demoing various forms of e-lit, followed by an e-lit exercise where you’ll re-imagine a pivotal scene of Frankenstein through the possibilities of e-lit (we’ll pass out handouts in class, but if you want a digital copy you can download this or see the assignment on my personal blog).

E-lit mentioned in class:

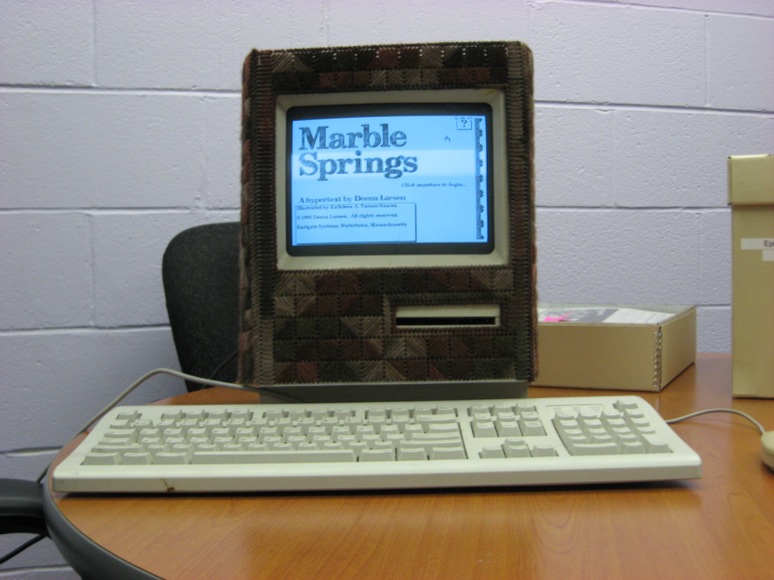

- Both Michael Joyce’s afternoon and Deena Larsen’s Marble Springs can be purchased from Eastgate Publishing. Or… make an appointment with MITH to read these and more e-lit on the original hardware, or visit the Deena Larsen Collection site to read more about Larsen’s work or watch a short video demo of Marble Springs.

- Larsen’s “Fun da mentals: Rhetorical Devices for Electronic Literature” is a fantastic site teaching basic approaches to writing e-lit.

- Caitlin Fisher’s These Waves of Girls is a 2001 Flash-based work.

- The Urban 30 is an example of a “fictional blog” based on WordPress (just like this site–well, the WordPress part!); in this case, multiple writers uses the blog community to write in as fictional characters. Urban 30 is particularly interesting because it tells a superhero story, a genre that was born and lived for a long time solely in comic books.

- The 21 Steps is a story told through Google Maps. Notice how this platform complements how important location is to the story.

- “Haircut” uses YouTube to create a choose-your-own-adventure video. If you’re curious how to do this, check out this tutorial on creating annotated YouTube videos.

- Stories created using texts and Twitter have taken off; “mobile phone novels” are especially popular in Japan, where this article claims they’ve “become so successful that they accounted for half of the ten best-selling novels in 2007.” This short article gives a sense of the kinds of stories people write via Twitter.

- In addition to individual-authored Twitter stories, large groups of strangers have used this platform for communal writing. The LA Flood Project was an event that encouraged Twitter users to tweet (with an #laflood hashtag) as if they were experiencing an apocalyptic flood in L.A. This page gives the brief timeline participants were supposed to follow; you can search Twitter for #laflood to see the story unfold, though it was most exciting in real-time (the latest tweets are just people rehashing the week-long event).

- And finally, the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) hosts the Electronic Literature Collection 1 and Collection 2, which display a wide variety of approaches to electronic writing.