Last week, Jen opened up the discussion of Richard Brautigan’s poem, “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace,” keying on a dark undertone she perceives in the poem and its resonance with scenes in The Matrix. As I got to the final line of the poem, I too felt a shiver of something cold and not quite right in the affective pitch of “loving grace.” Is there any support in the poem itself for this response, though? Or is my reading idiosyncratic? An artifact of the age I read it in?

I’m coming to the poem in the era of “ubiquitous computing,” where we are tracked in our transit through myriad electronic media, watched over in an everywhere-dense, ever more finely granular manner by people and systems we have not asked to do this for us. We do not have to imagine being watched over by machines; we are. In the past, the tools of mass surveillance have not had a happy history of use. In imaginative literature, they are a staple of dystopia.

“But,” Jen conjectures, “maybe… Brautigan’s speaker is a genuine optimist?” With this in mind, I reread “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace,” seeking evidence for either case. What I discovered surprised me, though pleasantly: I could find no explicit support for a foreboding or dark reading, and a preponderance of support for the contrary. Throughout, exclamatory parentheticals strain at the bonds of its present, three times urging: “right now, please!” or similar. Throughout, the emphasis is on harmony, mutuality (“mutually programming harmony”), peace (“where deer stroll peacefully”), liberation (“free of our labors”), Edenic return (“joined back to nature”), primitive domesticity (“returned to our mammal brothers and sisters”), affectively positive all the way from opening “I” to closing period. Everything in the poem rings with unalloyed enthusiasm. The poem seems to offer no intrinsic home to foreboding.

Brautigan tells us directly, too, what he feels so exuberant about.

In his envisioning, electronic machinery, an artifact of human craft, is naturalized, reintegrated with the nature it has emerged from and, imbued with agency, assumes a reciprocal relationship with living creatures. The computers, “watching over” all in title and the last two lines, are themselves now in some sense alive; and figuratively or not, they are imagined to someday “live together” in harmony with mammals (lines 4-6).

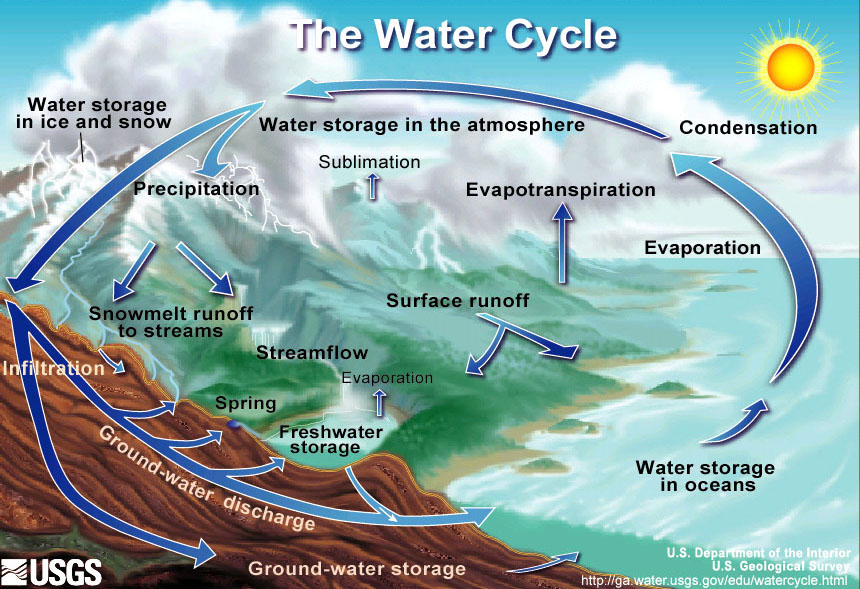

Harmony in this poem lives in the mutuality of agency between mammals and computers, in the “cybernetic meadow” (stanza 1, line 3), “cybernetic forest” (stanza 2, line 3), and “cybernetic ecology” (stanza 3, line 3). Reciprocity is essential to the original idea of the cybernetic. As developed by Norbert Wiener and those who came after him, cybernetics is a multidisciplinary study of regulatory systems (<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cybernetics>)—closely related to the mathematical theory of control, and control theory is fundamentally a theory of feedback loops, of actions and reactions, a give and take between causes and effects, inputs and outputs. Brautigan has imagined what physicists call a dynamic equilibrium, an equilibrium of flows: “Pure [liquid] water / touching clear sky.” Across this boundary water circulates, liquid to vapor, vapor to liquid, endlessly. Schematically, this reciprocity is a loop.

Figure 1: Cover of the 1954 paperback edition of Norbert Wiener's _The Human Use of Human Beings_, with reciprocating arrows.

Figure 2: U.S. Geological Survey illustration of the water cycle, in which water circulates through Earth's ecosystem, a cycle of action inviting cybernetic analysis. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_cycle

We have come far from the cultural moment into which Brautigan brought his poem. In our time, a kind of anxiety has interposed itself into the harmony Brautigan sees beckoning. This anxiety is sufficiently strong to reverse the poem’s gestalt, to flip it over to an ironic reading contrary to the one the poem most directly supports. While an ironic intent cannot be ruled out, nothing seems to be objectively present in the poem to disrupt its imagined harmony.

Naturalizing the artificial, Brautigan’s poem enacts a classically romantic breakdown of categories—the fusion of ideas that Samuel Taylor Coleridge so persistently espoused. What it operates on, though, are the formative tropes of romanticism itself. It doubles back on romanticism’s pastoral commonplaces, uniting nature with the most highly evolved of human artifice, computer machinery. The poem is paradigmatically techno-romantic. It is a techno-pastoral.

When we acquire a skill, it becomes a “second nature” built upon the original, as if we were born knowing how to do it. It starts out artificial and becomes natural, as we cease to have to think about performing it. In the same way technology, once adapted to the world around us, becomes as if it had always been there. Thinking about how the artificial is assimilated into the natural, and the unaccustomed becomes accustomed, I became curious about the career of the phrase “second nature.” I ran a quick Google Ngram Viewer query:

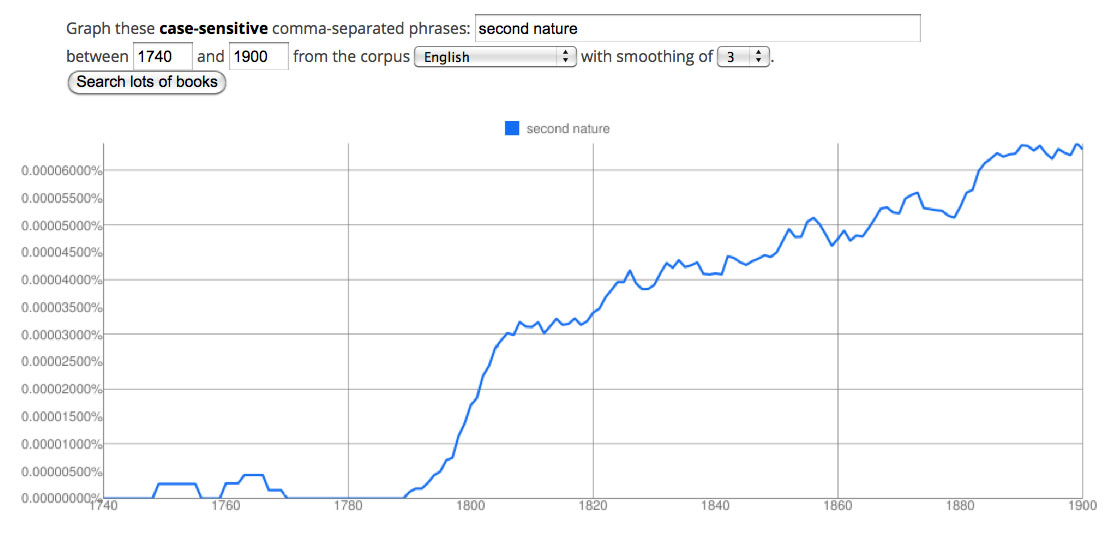

Figure 3: Google Ngram viewer for "second nature," from 1740 to 1900, with a 3-year smoothing applied. http://books.google.com/ngrams/

Curiously, the bigram “second nature” suddenly ticks upward in frequency around 1790, taking off rapidly later in the decade and on through the early years of the next century. That is, the phrase “second nature” came to prominence (in Google’s dataset) over the same time course that the first generation of English romantic poets came to maturity.