You might be interested in this essay by Jon Saklofske that evaluates the Blake Archive and imagines new ways of visualizing its content.

Also: how do doppelgangers fit into our definition of the monstrous?

Also: how do doppelgangers fit into our definition of the monstrous?

You might be interested in this essay by Jon Saklofske that evaluates the Blake Archive and imagines new ways of visualizing its content.

Also: how do doppelgangers fit into our definition of the monstrous?

Also: how do doppelgangers fit into our definition of the monstrous?

1. Poor Ernest Frankenstein. Type his name into Wikipedia and you’ll receive an amusing but reasonable redirect:

Ernest gets little page time. He isn’t mentioned in a letter to Victor in which Elisabeth does spend time discussing his other brother (William), and he oddly drops out of Victor’s remembrance instead of becoming more dear as his last remaining family member. (Stuart Curran’s Romantic Circles edition of Frankenstein collects the few references to Ernest here) What is Ernest even doing in the novel? I’d love to compare his place in the different versions of the work–I think it was Curran who suggested that Ernest is written slightly differently in the 1831 edition, and the fact that he remains in the book by that point (with Victor’s forgetting uncorrected) suggests Ernest’s vanishing role is worth exploring.

2. What do you make of the strange painting of Victor’s mother posed by her father’s coffin (a particularly creepy subject for Victor’s father to specifically commission)? Does this fit in with Steven Jone’s Freudian reading of Victor’s dream? Or were such subjects par for the course at the time? (Photographs of recently deceased children made to look like they were sleeping weren’t abnormal for the Victorians–though why paint a remembered person as dead/encased in a coffin when you could imagine him as alive within the painting? Did showing his true state conform to some sort of belief about naturalness/reality as reflected by painting?)

I gazed on the picture of my mother, which stood over the mantel-piece. It was an historical subject, painted at my father’s desire, and represented Caroline Beaufort in an agony of despair, kneeling by the coffin of her dead father. Her garb was rustic, and her cheek pale; but there was an air of dignity and beauty, that hardly permitted the sentiment of pity. (Shelley, Frankenstein, unknown page located in Project Gutenberg e-text)

3. In Jones’ Against Technology, he refers to “the story of Frankenstein’s creature who turns into a monster” (my emphasis, 1), an assertion that writes the character as first simply a creature, later monstrous. Is the monster’s monstrosity a result of his manner of birth, his grisly components and visage, or his evil actions? Does he become more or less monstrous during the novel as he gains knowledge, civilization, and other attributes of “humanity”–or does he perhaps simultaneously approach and recede from humanity?

If a Neo-Luddite would term Frankenstein a cautionary tale, a warning to those whose “hubris” (as Dan termed it) in developing artificial intelligence blinds them to its in inherent dangers, then what would they think of such problematic fiction as Asimov’s I, Robot or Disney’s WALL-E?

Both stories share a similar plot line: man invents machines, machines pose threat to man, a dissident machine rises up, saves man, and restores ‘natural order.’ Another parallel emerges in that both the machines of I, Robot and WALL-E receive programming from their human operators stating their primary function as human preservation and service (Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics and the directives given to various robots in WALL-E).

Both stories share a similar plot line: man invents machines, machines pose threat to man, a dissident machine rises up, saves man, and restores ‘natural order.’ Another parallel emerges in that both the machines of I, Robot and WALL-E receive programming from their human operators stating their primary function as human preservation and service (Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics and the directives given to various robots in WALL-E).

In I, Robot the super-computer V.I.K.I. ultimately identifies the most dangerous threat to humanity as people themselves. Logically, then, human beings must be severely limited and monitored for their own protection, resulting in robots ruling with iron fists. Though a rather frightening realization of Brautigan’s machines of loving grace, the androids of I, Robot really do have humanity’s best interest at heart. Likewise in WALL-E, the navigational component AUTO is following an outdated directive to avoid returning to earth, as it is supposedly unable to support human life. Hence he attempts to bar the ship’s captain from steering humanity home.

Though human beings do revolt in both stories, in true Neo-Luddite fashion, their feeble attempts are almost comical. The baseball-bat-swinging Chicagoan mob of I, Robot puts up a much better fight than the corpulent hover-chair-dwellers of WALL-E, but in both cases a cybernetic savior is needed. However, these cybernetic saviors’ ability to triumph rests in their distinctly human-like qualities. An unlikely hero, the plucky WALL-E saves the day by exhibiting one of the most laudable traits of self-sacrifice, a characteristic developed in earlier moments in the film when WALL-E expresses one of the basest of human desires in his longing for companionship, more specifically, the love of Eve. In his ability to love, WALL-E recognizes the worth of the greater good and willingly sacrifices himself for it. I, Robot’s much more complex hero, the android Sonny, also displays a broad spectrum of emotions throughout the film – anger, sadness, even conspiratorial trust. He is differentiated from homogeneous swarms of his hostile brethren by the fact that he is not only programmed with the Three Laws, but he has been endowed with the ability to choose to ignore them. Sonny’s creator, Dr. Lanning, endowed Sonny with reason and free will (two emphatically human rights), coupled with his ability to dream (which begs the question: Can a robot not only achieve the semblance of cognizance, but also delve into the subconscious?). Sonny is also given a predestined purpose, which manifests itself in his ability to defeat the rampaging V.I.K.I. through yet another show of willing self-sacrifice. When V.I.K.I. attempts to dissuade Sonny from his intent, questioning, “Do you not see the logic of my plan?” he thoughtfully replies, “Yes, but it just seems too heartless.”

Though human beings do revolt in both stories, in true Neo-Luddite fashion, their feeble attempts are almost comical. The baseball-bat-swinging Chicagoan mob of I, Robot puts up a much better fight than the corpulent hover-chair-dwellers of WALL-E, but in both cases a cybernetic savior is needed. However, these cybernetic saviors’ ability to triumph rests in their distinctly human-like qualities. An unlikely hero, the plucky WALL-E saves the day by exhibiting one of the most laudable traits of self-sacrifice, a characteristic developed in earlier moments in the film when WALL-E expresses one of the basest of human desires in his longing for companionship, more specifically, the love of Eve. In his ability to love, WALL-E recognizes the worth of the greater good and willingly sacrifices himself for it. I, Robot’s much more complex hero, the android Sonny, also displays a broad spectrum of emotions throughout the film – anger, sadness, even conspiratorial trust. He is differentiated from homogeneous swarms of his hostile brethren by the fact that he is not only programmed with the Three Laws, but he has been endowed with the ability to choose to ignore them. Sonny’s creator, Dr. Lanning, endowed Sonny with reason and free will (two emphatically human rights), coupled with his ability to dream (which begs the question: Can a robot not only achieve the semblance of cognizance, but also delve into the subconscious?). Sonny is also given a predestined purpose, which manifests itself in his ability to defeat the rampaging V.I.K.I. through yet another show of willing self-sacrifice. When V.I.K.I. attempts to dissuade Sonny from his intent, questioning, “Do you not see the logic of my plan?” he thoughtfully replies, “Yes, but it just seems too heartless.”

Both stories are problematic in their depictions of human-robot amalgamations. The stories’ villains are humanized (they are given names and voices), while the heroes go even further and present as manifestations of humans themselves. But really, can threatening technology be neutralized by technology that is more empathetic, more human? Taking into account that both cases, like the Morris worm, contain human error at their cores (V.I.K.I.’s logical conclusion was an inevitable result of her programming, and AUTO’s directive was straight from the mouths of humans), is it really a technological battle at all? I mean, what kind of battle is it where a human-created robot, operating on human-generated parameters, infringes on human rights and is subsequently destroyed by an altered, yet still human-created, robot, also operating on human-generated parameters? It almost seems to be a gigantic battle game – will love triumph over logic, does self-sacrifice trump self-destruction? – with the all-too-human warfare of vices and virtues played out on a grander technological stage.

While reading through Jones’ chapter on Frankenstein, I was particularly drawn to the section’s discussion on Victor’s laboratory and his relationship with science in general. I immediately grabbed the novel and found my comments scribbled beside the text, specifically the scene of Frankenstein’s monster’s creation: “vague description,” “so I guess electricity is involved somehow?” and “is this even science?”

For a novel that supposedly pioneered an entire genre, aptly named science fiction, there is very little science to be found in Frankenstein. Jones notes that this choice was made either because Shelley did not know how to describe the science involved, or to express “that technology is not the point of the story” (Jones, 19). The scene itself utilizes vague terms such as “materials,” “the instruments of life,” and the repetition of the word, “secret” (Shelley, 35-38). Jones argues that the scene’s description resembles alchemy, painting Frankenstein as an alchemist or mage. Moreover, in his studies, Frankenstein claims to be more interested in the ancient scientists, who dream big (and promise “impossibilities” such as alchemy and immortality), than the “modern masters [who] promise very little” (Shelley, 30). All of this discussion links Frankenstein with figures such as Faust and Prospero as well as Prometheus. So in a way, Frankenstein is, or wants to be, a magician.

“And now for something completely different,” as the folks of Monty Python would say. I want to bring in the genre of fantasy by turning to Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea. Le Guin is a major science fiction author (no doubt influenced by Mary Shelley), but this novel is one of her forays into fantasy. The novel follows a young wizard named Ged who, after accidentally conjuring a monster or shadow creature in his youth, spends the next stage of his life faced with a number of obstacles while simultaneously avoiding the dark entity he had himself created.

Sound familiar? Despite being rooted in fantasy, Earthsea and its structure resemble Frankenstein. In an act of hubris, each protagonist plays god and creates (whether purposely or accidentally) a monstrous entity that never should have existed. Just as Frankenstein spends the better part of the novel trying to “live his life” while his monster destroys everyone around him, so too does Ged (although he does save his fair share of people). Their turning points even resemble one another. After returning home, Ged reunites with his teacher, who convinces him to pursue his shadow, and suddenly the tables are turned. Frankenstein is not so decisive or confident, but his moment of clarity comes after Elizabeth’s death (or, to a lesser extent, Clerval’s), in which he vows to pursue the monster until one kills the other. Ged is successful in the end, Frankenstein far less so, but one can see the resemblance.

Other parallels exist (Walton even has a counterpart in Earthsea), but I won’t go into them. There are plenty of differences, of course, in content as well as tone and theme. Shelley’s novel humanizes the monster, while for the most part Ged’s shadow remains an abstraction. More importantly, Earthsea is about learning to face your greatest fear (for Ged is able to defeat his shadow in the end, albeit by merging with it), while Frankenstein is more of a cautionary tale.

But despite these differences, Le Guin owes a great debt to Shelley. The point I am trying to make actually ties in perfectly with the reading. If “technology is not the main point of the story,” as Jones argues, then surely one can replace the novel’s science with another force without damaging the story in the slightest. I argue that despite their differences, Le Guin’s novel is an exercise in this viewpoint. Science or magic, both tales follow similar structures and share important themes. With this in mind, arguing that Frankenstein is wholehearted “anti-science” would be akin to arguing that A Wizard of Earthsea is “anti-magic.” The lesson here is not in technology, but in hubris, responsibility, imagination, creation, and a million other abstract terms I will not list here.

In a way, then, with its references to magic and alchemy, Frankenstein helped establish not one genre, but two: science fiction as well as fantasy. Not too shabby.

My art professor in college just directed me toward this interview with artist Steve Seeley, in which the interviewer describes Seeley’s work as:

figurative work [that] often features the juxtaposition of human bodies and animal limbs, or heads. Sometimes alien parts make an appearance as well. He integrates old and new surfaces, incorporating the nostalgia of his childhood into a present assemblage… Seeley’s icons adopt the iconography of saints and superheros with all of the mystical proportions childhood bears with them. To re-erect and reexamine the Gods of childhood in effort, perhaps, to examine those ancient power structures. In Seeley’s case, they often become hybrid.

I looked through Seeley’s work and found it timely and illustrative for our being in between thinking about hacking and thinking about the monster. The following photo-examples I pulled from Seeley’s Delicate Matter:

![]()

![]()

Though the superhero imagery certainly resonates with a particular nostalgic part of me, it is the two “Icons” that I’ve been coming back to all morning. In a recent tweet, I suggested that the monster essentially is an uncanny subversion of nature, and that we come to fear these monsters out of a deep cognitive dissonance that begins with (is triggered by) their altered appearance, but quickly moves into something much more substantial (and permanent) when we become aware of the fact that the unseen characteristics, and thus the very nature of, the monster must have been altered too. To then make the monster a holy monster is to redefine one’s relationship with the Uncanny from one based in Fear of the Monster to one based in Reverence for the Sublime.

That Seeley has created a narrative for how monsters become, and then become holy, and that such a narrative is the result of human technological developments in space travel, and that the monster is then the natural evolution of life on earth (both in terms of the space-dwelling ‘alien’ men and then earth-dwelling ‘hybrid’ animals) intrigues me to no end:

As for the difference between man and animal, there isn’t a huge difference for me. In the “delicate matter” series, the story so far is that man has left earth for outer space because he becomes enamored with something he can’t comprehend, something that is entirely different from what he knows. He leaves earth on bad terms with the animals and while he is gone animals become what they were destined to be, a transformation per se, into heavy metal loving, super power using, pop culture loving creatures. When man gets to space he finds it to be less than he had hoped, and he tries to come back but the animals refuse. So man is stuck in space while animals take he’s [sic] place back on earth, essentially filling his old shoes, and becoming the new ‘man’…The head swapping was a way for me to even more-so humanize the animals. Initially all the human body, animal headed figures in my paintings were referred to as ‘saints,’ figures that were idolized by the other animals and which usually also adorned halos.

Keats suggests that men of Imagination ought to possess “Negative Capability,” essentially the ability to comfortably occupy a space in which paradoxes, contradictions, and elements of the Uncanny abound, without needing to reach for reason or logic to make sense of the experience. I suspect Seeley’s gesture of finding (transcendent?–or at least substantial) value in the monster, and proving as much by elevating him to ‘sacred’ status via the religious icon, is one way to articulate how it is that we can paradoxically fear and ‘make-holy’ an incomprehensible, Uncanny figure.

Edit: 18 March 2012–An Addition

So now, a month and a half later, I’m thinking about Seeley’s work again: I’m home for Spring break, getting my tattoo touched up, and trying to find a new place on my body to ink the deer Icon posted above. There’s something powerful about the image, something that rings deeply true to me about the way we encounter the sublime-in-the-Uncanny. But perhaps I should back up for a second…

Two weeks ago I was fortunate enough to be able to sit on a conference panel to present a paper I had written–and am obsessively adding to–exploring elements of the Uncanny in prosody, particularly something I’m calling poetry’s “Uncanny Sound.” One of the more apt poems I’ve come across in this project is Hart Crane’s “The Hurricane,” a poem in which Crane, standing in the eye of a hurricane, watching it destroy the world on all sides of him, is forced to create a new language to echo–and enact!–the impressiveness and sublimity (i.e. the ‘too much’-ness) of a natural disaster, a language in which old words are razed to make material suitable for the “Uncanny event” and new words are joined to antiquated, Biblical suffixes to anchor the world in some sense of supernatural history. All of this then comes together in an artificial ‘hybrid’ language of contradictions and anachronisms (one half of poetry’s “Uncanny Sound”) that serves the magnificent power of such an experience well, for as the highs are made low with “summits crashing” and lows are made high when “sea-kelp” goes to “high heaven dashing,” so too is the highest language brought down among base terms and the lowest language elevated to the level of scripture. To speak this poem aloud, I’ve discovered, is to summon the power of the hurricane; to become the hurricane, for a time; to internalize it and bring it in you.

So I’m bringing this up alongside my thinking on the Icons because I sense Seeley’s understanding of the natural world of animals corresponding with Crane’s relationship with the natural world of weather, specifically that there is something unnatural inherent to the natural world, unnatural in that there is such otherness (and power in this otherness) present in the natural world at special times that one simply cannot experience as native, incidental, familiar, or safe, but foreign, deliberate, disorienting, and dangerous instead.

What’s happening in these special moments, I’m thinking, is a shift from what Martin Buber calls an I-It relationship with the world to an I-Thou relationship. The relationship one has with ordinary things as objects of experience and use Buber calls I-It, an essentially “detached” relationship (e.g. the one might have with pen); the attitude of the I here is that the It is separate from himself, an object that can be intriguing to observe or fortunate to use, but nothing more. The relationship one has with others, on the other hand (no pun intended), Buber calls I-Thou, and this “involves the whole person;” here, the I, a meaning-making individual, “addresses” a Thou as a meaning-making subject, not an object, and is thus “addressed” as a subject in return. These I-Thou “encounters,” Buber claims, constitute “real life,” in that they are the only authentic and real (i.e. meaningful) relationships one may expect to find in the world. By addressing the existence of the Thou in another, one effectively moves himself toward an intimate, subject-to-subject relationship with the Ultimate Thou, which is God.

So when I say that

I suspect Seeley’s gesture of finding (transcendent?–or at least substantial) value in the monster, and proving as much by elevating him to ‘sacred’ status via the religious icon, is one way to articulate how it is that we can paradoxically fear and ‘make-holy’ an incomprehensible, Uncanny figure.

…what I’m suggesting is that Seeley is finding in the natural world a Thou, not an It; not a world to simply be seen or projected on or used, but a world that looks back, projects back, and uses.

This is a fairly powerful claim as an artistic statement, but more so as a statement of ‘the nature of things’ (as Lucretius would have it). As we begin to transition further into Romanticism and the Romantic poets–the second half of this Technoromanticism idea we’re orbiting–I think we’ll find this conversation sprouting up again and again, begging us to evaluate and then re-evaluate our relationship to our (un)natural world through art in both the traditional sense (painting, music, poetry) and then the non-traditional sense (?, ?, ?).

I was stumbling around the Internet (Wikipedia specifically) yesterday morning, trying to enrich my knowledge of Frankenstein. I’m sure all of you can relate to the endless wandering Wikipedia offers with the hyperlinks embedded in the articles. After a while, I found myself on the page for Golems, which apparently have their origins in the Bible. And eventually I thought of some of the modern representations of golems, especially organic, golem-like figures (such as Frankenstein), and I thought of one of my favorite video games:

Bioshock is already known in the gaming world as a very literary and smart game. As a response to Ayn Rand’s objectivist theories, the world of Bioshock is an underwater city called Rapture, comprised of districts with grandiose, allusive names like Hephaestus, Apollo Square, Aphrodite, etc, and governed by the doctrine that man should be free to reap the rewards of his work without censor and restriction. This, naturally, leads to violent anarchy, and the course of the game toys with the theories of uninhibited free will and living as an ignorant slave, as the player explores this dystopian world.

But while that is the publicly acknowledged critique of the game’s literary value, I have begin to muse about other issues it explores and other works it may be in dialogue with. From the title alone, some sort of collision of life and something else can be inferred. Bioshock: a shock to life by something disruptive, surprising, or strange, or perhaps something that restarts or recalibrates life. The connection to Frankenstein should be apparent at this point.

The large golem-like figure dominating the image is certainly suggestive of some sort of strange form of life in any case. And, to those who have not played the game, one of the major plot points is the discovery that these creatures, the so-called Big Daddies, are real men, mechanically and genetically modified to perform specific (and violent) functions as guardians and enforcers.

But this is not the only example of life-hacking and a relationship with Shelley’s novel. The entire game itself revolves around a protagonist whom was engineered by a “mad scientist” father for the purpose of extending life. This is not initially known, but gradually revealed. In essence, players control a Frankenstein’s monster that was not rejected by the father, but manipulated and continually “built” over the course of the game by way of the strange genetic substance called ADAM, a process that was necessary for survival in Rapture.

As I continue to read through Frankenstein, I’ll probably keep the relationship with Bioshock in mind, as the latter seems to be directly related to the former in questioning the role of science and the bleak possibilities of tampering with life. However, at the moment, I feel my thoughts are too premature to begin to try to fully explain or even organize.

But for one last tidbit, attached below is a link to a small, but scholarly, discussion, begun by Tim Welsh at the University of Loyola, on Posthumanism and Bioshock that some might find interesting:

http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/imr/2011/03/10/would-you-kindly-bioshock-and-posthuman-choice

Last week, Jen opened up the discussion of Richard Brautigan’s poem, “All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace,” keying on a dark undertone she perceives in the poem and its resonance with scenes in The Matrix. As I got to the final line of the poem, I too felt a shiver of something cold and not quite right in the affective pitch of “loving grace.” Is there any support in the poem itself for this response, though? Or is my reading idiosyncratic? An artifact of the age I read it in?

I’m coming to the poem in the era of “ubiquitous computing,” where we are tracked in our transit through myriad electronic media, watched over in an everywhere-dense, ever more finely granular manner by people and systems we have not asked to do this for us. We do not have to imagine being watched over by machines; we are. In the past, the tools of mass surveillance have not had a happy history of use. In imaginative literature, they are a staple of dystopia.

“But,” Jen conjectures, “maybe… Brautigan’s speaker is a genuine optimist?” With this in mind, I reread “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace,” seeking evidence for either case. What I discovered surprised me, though pleasantly: I could find no explicit support for a foreboding or dark reading, and a preponderance of support for the contrary. Throughout, exclamatory parentheticals strain at the bonds of its present, three times urging: “right now, please!” or similar. Throughout, the emphasis is on harmony, mutuality (“mutually programming harmony”), peace (“where deer stroll peacefully”), liberation (“free of our labors”), Edenic return (“joined back to nature”), primitive domesticity (“returned to our mammal brothers and sisters”), affectively positive all the way from opening “I” to closing period. Everything in the poem rings with unalloyed enthusiasm. The poem seems to offer no intrinsic home to foreboding.

Brautigan tells us directly, too, what he feels so exuberant about.

In his envisioning, electronic machinery, an artifact of human craft, is naturalized, reintegrated with the nature it has emerged from and, imbued with agency, assumes a reciprocal relationship with living creatures. The computers, “watching over” all in title and the last two lines, are themselves now in some sense alive; and figuratively or not, they are imagined to someday “live together” in harmony with mammals (lines 4-6).

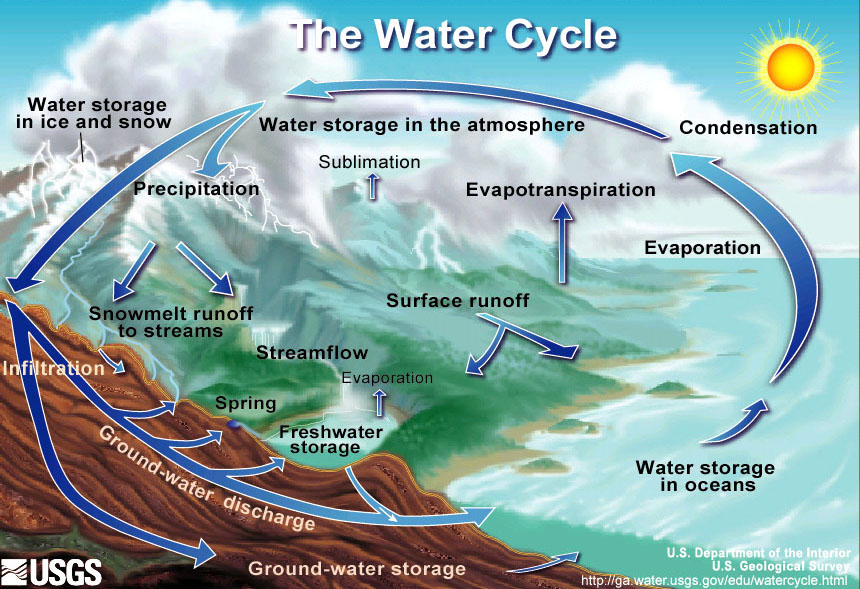

Harmony in this poem lives in the mutuality of agency between mammals and computers, in the “cybernetic meadow” (stanza 1, line 3), “cybernetic forest” (stanza 2, line 3), and “cybernetic ecology” (stanza 3, line 3). Reciprocity is essential to the original idea of the cybernetic. As developed by Norbert Wiener and those who came after him, cybernetics is a multidisciplinary study of regulatory systems (<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cybernetics>)—closely related to the mathematical theory of control, and control theory is fundamentally a theory of feedback loops, of actions and reactions, a give and take between causes and effects, inputs and outputs. Brautigan has imagined what physicists call a dynamic equilibrium, an equilibrium of flows: “Pure [liquid] water / touching clear sky.” Across this boundary water circulates, liquid to vapor, vapor to liquid, endlessly. Schematically, this reciprocity is a loop.

Figure 1: Cover of the 1954 paperback edition of Norbert Wiener's _The Human Use of Human Beings_, with reciprocating arrows.

Figure 2: U.S. Geological Survey illustration of the water cycle, in which water circulates through Earth's ecosystem, a cycle of action inviting cybernetic analysis. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_cycle

We have come far from the cultural moment into which Brautigan brought his poem. In our time, a kind of anxiety has interposed itself into the harmony Brautigan sees beckoning. This anxiety is sufficiently strong to reverse the poem’s gestalt, to flip it over to an ironic reading contrary to the one the poem most directly supports. While an ironic intent cannot be ruled out, nothing seems to be objectively present in the poem to disrupt its imagined harmony.

Naturalizing the artificial, Brautigan’s poem enacts a classically romantic breakdown of categories—the fusion of ideas that Samuel Taylor Coleridge so persistently espoused. What it operates on, though, are the formative tropes of romanticism itself. It doubles back on romanticism’s pastoral commonplaces, uniting nature with the most highly evolved of human artifice, computer machinery. The poem is paradigmatically techno-romantic. It is a techno-pastoral.

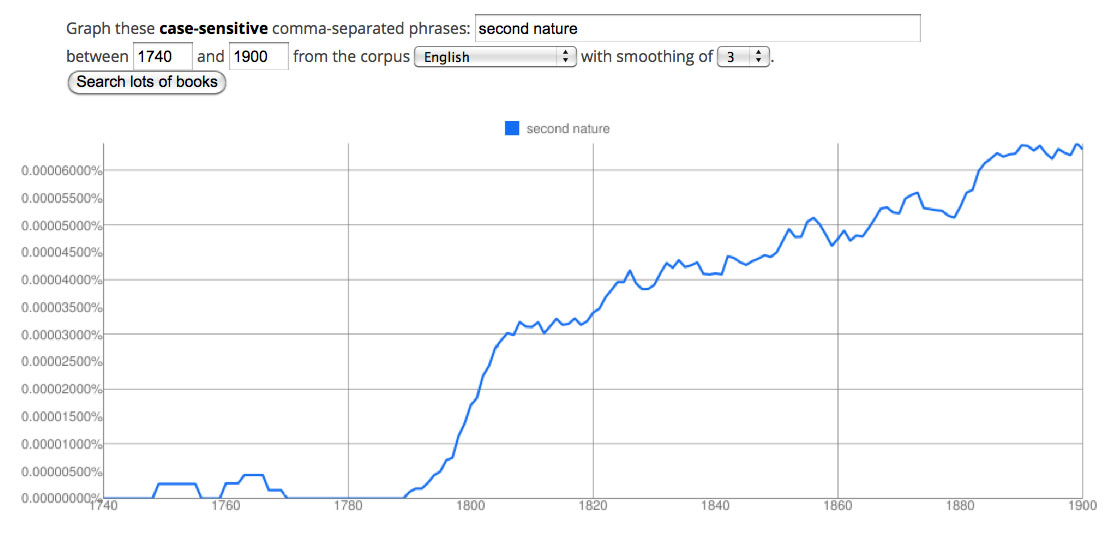

When we acquire a skill, it becomes a “second nature” built upon the original, as if we were born knowing how to do it. It starts out artificial and becomes natural, as we cease to have to think about performing it. In the same way technology, once adapted to the world around us, becomes as if it had always been there. Thinking about how the artificial is assimilated into the natural, and the unaccustomed becomes accustomed, I became curious about the career of the phrase “second nature.” I ran a quick Google Ngram Viewer query:

Figure 3: Google Ngram viewer for "second nature," from 1740 to 1900, with a 3-year smoothing applied. http://books.google.com/ngrams/

Curiously, the bigram “second nature” suddenly ticks upward in frequency around 1790, taking off rapidly later in the decade and on through the early years of the next century. That is, the phrase “second nature” came to prominence (in Google’s dataset) over the same time course that the first generation of English romantic poets came to maturity.

After class the other night, I watched (okay, here I must admit to being rather a nerd) Battlestar Galactic with my boyfriend. For those of you who haven’t seen the 2004 series (which differs somewhat from the original): Mankind created the Cylons as slaves, but the Cylons developed sentience. The Cylons, angry after years of servitude and fearful that their creators might destroy them now that they are sentient, decide to strike first and destroy the humans. This summary is simplistic at best; the problems between the humans and the Cylons are compounded by religious differences (the Cylons are monotheistic, while the humans believe in a pantheon of gods), grievances from the long war, desires to prove themselves, and more. Significantly, (and why the show reminded me so strikingly of our discussion in class) during the war, the Cylons evolve from their original form:

To a model which looks virtually indistinguishable from humans:

However, unlike humans, the Cylons are limited by only a set number of human-like appearances, multiple copies of the same model being possible, both male and female.

What all this builds up to, in a round about way, is that not only do the Cylons illustrate the Uncanny Valley (some humans, overlooking the war and the differences, develop feelings for the humanistic Cylons, even fall in love and start families with them), but the Cylons bring into question what it means to be human. More than just in appearance, the Cylons are almost indistinguishable from mankind. Like humans, the Cylons have religious beliefs, emotions, a respect for life (even though they themselves can be reloaded into new bodies like a computer program might be moved from one computer to another), ability to suffer pain, desires to reproduce and have offspring, ability to dream, and more. In fact, the Cylons are so similar to humans that they have even developed traits that, while we should like to call “inhuman,” the show more than clearly demonstrates are all too human. Both the Cylons and the humans make use of torture, though one of the first instances of it in the series is the humans is the humans raping and beating a female Cylon. Further, neither the humans nor their creations are opposed to suicide bombings, terrorism, and murder (even murdering their own people not simply as acts of war). The humans, when speaking of these acts committed by the Cylons call them “inhuman,” yet when their own people do it, one must admit that it is all too human. The humans simply argue that their use of such tactics are out of the necessity of war, yet the Cylons could as easily claim the same. The Cylons are so indistinguishable from their creators that they possess both mankind’s best and worst characteristics.

In spite of this, the humans abhor the Cylons, calling them “monstrous” and “inhuman,” yet when it comes to putting one’s finger on just what makes them different from the humans it is hard. Is simply declaring it is because they are not us–our creations–enough? Perhaps it is because they make us all too aware of the inhuman aspects of humanity that we wish to distance ourselves from them. As we have discussed in class, the line between us and technology (or us and them) is uncertain and shifting at best being so dependant on how one defines technology and it brings into question our identity as humans.

In one of the most recent episodes I’ve seen a doctor emerges from a medical tent, covered in blood. A Cylon approaches him and, indicating the blood, asks if it is Cylon or human as “it all looks the same.” This is a perfect summation for my argument: There is almost no difference between the Cylons and the humans, indistinguishable from each other even by members of the same race. Simply by existing, the Cylons bring into question how we differentiate between human and inhuman. The same question that is approached through Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in discussion of monstrosity: Is it possible that humans can be less “human,” more “monstrous,” than their creations? Both the Cylons and Frankenstein’s Wretch would readily answer yes; humanity can be inhuman and the inhuman can be far more humane, at times.