Deconstructing the Male and Female Gothic using Woodchipper

Posted by in Spring 2012 | Uncategorized - (4 Comments)During my time as an undergraduate at Lebanon Valley College, I took an independent study on early Gothic literature. Throughout this course, I was continually confronted with prejudices against the Gothic as being incapable of offering any academic merit. This was particularly the case during the time in which the works were written—having been seen as terrorist writing meant to simply excite the senses rather than communicate any high intellectual notions. Yet, even in scholarship written in the past decade, I came across several scholars who maintained these beliefs—perhaps not as blatantly, but they were apparent nonetheless. One of the more disruptive ways that this prejudice presented itself was through the further categorization of the Gothic into categories of male and female. The male Gothic was built up around The Monk, while the female Gothic was founded based on The Mysteries of Udolpho. In my final paper, I explored several Gothic works from the Romantic period, including these two, in order to break down the categories of male and female Gothic and prove once and for all that these categories hinder our ability to understand the complexities of the Gothic genre. So, when we first formulated this Woodchipper experiment around Gothic works, I was extremely excited! First and foremost, my goal was to use Woodchipper to prove that my thesis was correct.

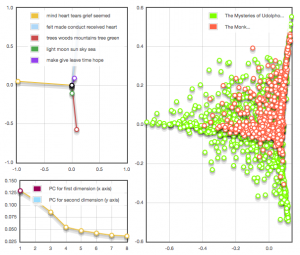

The first run that I would like to highlight uses Udolpho and The Monk. In this run, we can see divergences between the two texts. One obvious point where Udolpho breaks away from The Monk is with the category of nature. This makes sense since Udolpho features pages upon pages of sublime descriptions of Emily’s several journeys through mountains and valleys. Udolpho also pulls more strongly toward the “Sentiment” category featuring the words “mind,” “heart,” “tears,” “grief,” and “seemed.” This, once again, is to be expected since Udolpho is the primary female Gothic text from which the ideas of sentiment and suspicion (“seemed”) arise as key facets of the genre. The Monk holds back from this, sharing a stronger pull with Udolpho toward “felt,” “made,” “conduct,” received,” and “heart.” Although my group has generally agreed that this category is indeterminable, some of these words concern actions and subjectivity—“felt,” “received,” and “heart.” Since the Gothic genre in general has been associated with interiority and subjectivity, we can perhaps see this category as picking up on these characteristics.

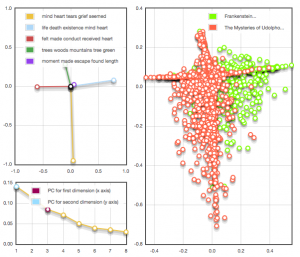

The next run that I would like to highlight features two female authors. I was particularly pleased with this run since it showed a clear divergence between Udolpho and Frankenstein. Naturally, I would suppose these two texts to be somewhat opposed to each other since Udolpho features no true supernatural element (a typical characteristic of female Gothic), while Frankenstein clearly has an unnatural being—a “monster”—as one of its main protagonists (a typical characteristic of male Gothic). I definitely felt like Woodchipper was behind my conclusion that the categories of male and female Gothic fail to live up to their names when analyzed closely. Although the texts do align in some areas, the clear pull toward “Spiritual” for Frankenstein and the clear pulls toward “Indeterminable/Subjectivity(?)” and “Sentiment” for Udolpho reaffirms the tendency of female texts to work against a clear-cut categorization of female Gothic.

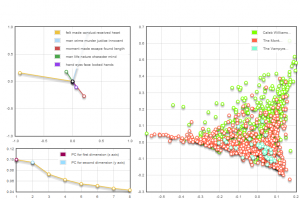

The third run that I am presenting here featured three Romantic Gothic works by male authors: The Monk, The Vampyre, and Caleb Williams. Although the general splash pattern appears to be similar between The Monk and Caleb Williams (The Vampyre was way too short to get any definitive pattern), each work demonstrates a stronger pull than the other in one of the two main directions. Caleb Williams pulls stronger toward “man,” “crime,” “murder,” “justice,” and “innocent” (“Crime”) than The Monk. Considering the content of Caleb Williams, this makes sense. Although male Gothic, Ambrosio’s greatest crime in The Monk is rape, not murder. On the other hand, The Monk pulls more strongly toward our “Indeterminable” category, though Caleb Williams does have an outlier the furthest toward this category. However, overall, Woodchipper still notes a divergence between texts within the male Gothic, just like it did within the female Gothic.

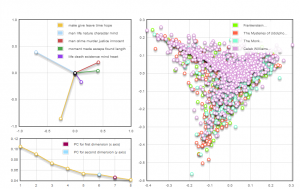

In order to better see how the male and female authors align with one another, I decided to use the four primary male/female Gothic texts that I have been focusing on in the same run. As we can see, the patterns appear to be relatively in line with one another with only a few outliers. For me, I saw this as proof of the inability for the male/female Gothic distinction to hold up when texts are examined. All four texts show a strong pull toward “man,” “life,” “nature,” “character,” and “mind” which could be called the “Sublime Reflection” topic and could easily be associated with the Gothic’s concern with interiority. A second strong pull comes from the topic “make,” “give,” “leave,” “time,” and “hope.” This topic is another indeterminable category. Yet, one could perhaps associate this with subjectivity and interiority as well, since the word “I” can feasibly stand in front of all of these words except for time. The passages that follow this trajectory somewhat lend themselves to this conclusion featuring moments of resolve by the characters in which they express their steadfastness in their decisions (ex. “Leave me! Your entreaties are in vain!” [The Monk] and “I have given a solemn promise . . . to observe a solemn injuction” [Udolpho]). In any case, the alignment of these texts helps to reaffirm my premise that the male Gothic and female Gothic are unstable categories that fall apart upon close examination.

Overall, I would claim that Woodchipper was able to reaffirm my statement that strategies used to delineate between the male and female Gothic do not uphold themselves when placed under scrutiny. Although there were many problems faced when encountering Woodchipper, such as the inability to look under clusters of nodes and the inability to decide which topics pop up during runs, I was still able to provide some tentative evidence for my initial claim. While there is much room in my conclusion for debate, I found the results from Woodchipper to be very helpful. With further study, I believe that Woodchipper could be used to disprove without a doubt the fallibility of the categories of male and female Gothic.