As part of my final project: a website unbibliography, http://digitalliterature.net/bookhacking, providing a survey of readings on the idea of hacking the book: rewiring, reconsidering, and rebelling against the conventions of the traditional print codex, beginning with William Blake’s masterful Romantic productions. The readings cover the ways in which Blake hacked the book, how formats such as the Total Work of Art and artists’ books have further deformed the standard print tome, and how digital editions—particularly those electronically remediating Blake’s hacked books—themselves function as explosions of the conventions of the book. The readings pay particular attention to the visual design of books and online editions, treating graphical decisions as critical features of these texts and creating a catalog of opportunities and techniques for hacking the book.

This March, I spent the last few days of my spring break in Louisville, Kentucky. As I may have mentioned in class, I am on the board of LMDA and for the past several years we have held our spring board meeting in Louisville during Humanafest at the Actors Theatre of Louisville. It is a wonderfully dizzying two and a half days of play-going, panel discussions, and conversations about theatre in lobbies and in restaurants. This year the festival featured works that varied in theme and genre quite a bit. My personal favorite struck an emotional chord with me that now rarely happens with a show I have not worked on, or am not personally and professionally invested in. Mona Mansour’s The Hour of Feeling is a haunting look at the meaning of home, set in 1967 in Palestine and London. I do not mean this essay to be a review of the play. You can find out more about the piece by watching this clip and reading this review (which opens with the line: “If you want to understand the Sixties, go back to the early 1800s, when Romantic poets like William Wordsworth rejected classical rationalism to celebrate the beauty of deep emotion and the sanctity of individual experience.”), and doing the usual googling routine. I am writing about the play on this blog because of the connection it has to our class materials, particularly our discussions on prosthetics of imagination and memory and gender.

The protagonist of the play is Adham, a young scholar from Palestine who has been invited to London to give a scholarly lecture on Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks o the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798.” He brings his new wife with him and, while they are in London, war breaks out in the Middle East (one they could not have known would be so short and yet so long). On the evening after his triumphant lecture, while at a party, they receive news of the war. Adham’s wife, Abir, is frantic to return home immediately. Adham is less certain that he wants to return to Palestine (known then as Jordon, “sort of”) and to his mother, who appears to him during his more introspective and anxious moments in the play.

The title of the show is from another poem from Lyrical Ballads, “Lines written at a small distance from my House, and sent by my little Boy to the Person to whom they are addressed,”[1] and selected lines from it are projected on a scrim or quoted during the course of the play (the sections in bold are the ones projected or quoted during this production): (more…)

In my part of the group blog post for the encoding group, I began my section by discussing the difficulty of beginning to the process of encoding when you feel discomfort with the tools of encoding. After discussing how I moved through my discomfort, I ended my section of the article by beginning to contemplate other possibilities for digital encoding and archiving, particularly in relation to my field of theatre and performance studies. I would like to take the opportunity in my individual post on our group project to expand on some of these questions on archiving and theatre that our encoding has brought to light for me.

When I have attempted to describe our encoding project to others outside of our class, many people are confused as to why it would be necessary to take an image of a work and do more than simply post it to a web site. In order to explain our encoding work to these people, I have often described it as taking text and turning it into data via the encoding. I have referenced the examples we examined in Mining the Dispatch and I have pointed out how these types of projects make it possible for the humanities to consider questions it might not have been able to consider prior to this technology. But, first, I would like to touch a bit more on our project, and its significance as performance.

As Peter Stallybrass points out in his response to Ed Folsom, the Walt Whitman archive was a chance to “liberate Whitman from the economic and social constraints that govern archival research,” (1580) and the existence of digital archives may actually be encouraging visits to and use of the physical archives. However, Stallybrass then continues, “databases are neither universal nor neutral, and they participate in the production of a monolingual, if not monocultural, global network.” (1583) Jerome McGann, also in a response to Ed Folsom, is critical of Folsom’s description of the archive as a database, pointing out that, not only is database creation influenced by those who create the database, but that human perception and perspectives also influence how we interact with the database. McGann says: “these tools are prosthetic devices, and they function most effectively when they help to release the resources of the human mind – in short, when their interfaces are well-designed.” (1591)

Folsom is correct that an archive is a database, as he says in his rebuttal, but I believe Stallybrass and McGann are also correct to point out the human component in database (and, hence, archive) construction and use, and our desire to craft narrative from a database. After all, what is it that historians do if not take information from a database (whether it is a manuscript in a library, the letters of someone from the past, or the memories of a person being interviewed today, or other such information) and create a plausible, interesting story for a reader? At both this stage and at the other end of the process, when I database (either physical or digital) is being created, I would argue something else is happening. The very existence of this human component and the action required by a person in relation to an archive indicates that archives/databases are performed.

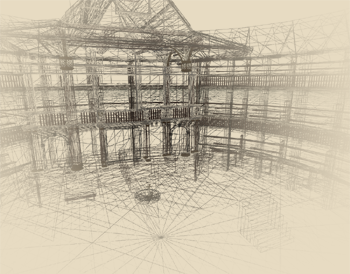

Our group took on the task of encoding Mary Shelley’s manuscript of Frankenstein for the Shelley Godwin Archive. In a sense, we performed Frankenstein, page by page. We had to make decisions as to what we were seeing on the page and what on the page was important, if we agreed with the transcript of the pages we had been given (if we thought they matched the image of the scanned page), how many of the non-language marks on the page were to be represented in the encoding and how to represent the page spatially using the XML language. We had to do something, we had to act in order for the text, in order for the page, to become data. I had to ask, for example, if the mark at the bottom of a page, a sort of curve under the last paragraph, was a doodle or just an errant mark. Was this a mark of intention or accident? And did it belong with the text, or represented as apart of the paragraph? My typing laid claim to the author’s intention, and provided interpretation for how a reader would eventually view this as data. For that mark to exist as data, first I had to perform it.

Diana Taylor writes in The Archive and the Repertoire,[1] “My particular investment in performance studies derives less from what it is than what it allows us to do. By taking performance seriously as a system of learning, storing, and transmitting knowledge, performance studies allows us to expand what we understand by ‘knowledge.’ This move, for starters, might prepare us to challenge the preponderance of writing in the Western epistemologies. . .writing has paradoxically come to stand in for and against embodiment. When the friars arrived in the New World in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as I explore, they claimed that the indigenous peoples’ past – and the “lives they lived” – had disappeared because they had no writing. Now, on the brink of a digital revolution that both utilizes and threatens to displace writing, the body again seems poised to disappear in a virtual space that eludes embodiment. Embodied expression has participated and will probably continue to participate in the transmission of social knowledge, memory, and identity pre- and postwriting. Without ignoring the pressures to rethink writing and embodiment from the vantage point of the epistemic changes brought on by digital technologies, I will focus my analysis here on some of the methodological implications of revalorizing expressive, embodied culture.” (16)

Just as Lev Manovitch put the database and narrative in competition with one another, Taylor here has put digital space and embodiment at odds with one another. To be fair, her study is not at all concerned with digital technology, and this section of her introduction is one of the few places she addresses virtual space. But the contrast she makes between the virtual and the embodied are clear, and I would question that dichotomy as a false one. Can the digital be embodied? The digital can be performed, and those performance require not just a human mind, but also a human body – eyes to see the computer screen (or ears of hear the audio interpretation) and fingers and hands to type on the keyboard, at a minimum. An establishment of the notion that database and (digital) archives are performed leads us to conclude that they are also embodied. Database and archives also allow us to do, and open up possibilities for what we might do.

There are many possibilities for the use of digital archives in relation to the study of theatre, theatre history, and performance. I believe that the performative nature of digital archives makes the pairing between a database format and theatre quite natural. There are in fact, several projects already in existence, including the Shakespeare Quartos Archive, Theatre Finder, and the Visual Accent and Dialect Archive at MITH, among others. I would like to consider for a (brief) moment two other possible projects, and the implications for performed databases that each holds.

The first project is the American Theatre Archive Project. As stated on its web site this archiving project “is a network of archivists, dramaturgs, and scholars dedicated to preserving the legacy of the American theatre. ATAP is guided by the work of four Committees, which help develop partnerships, facilitate communication, create guidelines, seek funding, and disseminate best practices. Location-based Teams help individual theatre companies evaluate their records, develop an archiving plan, and secure funding to support long-term archive health. Once created and made accessible to theatre makers, scholars, patrons, and funders on premises online, and/or in a repository, a theatre’s archives support institutional integrity and development.”[2]

There is a brief mention of online archives in the above description. The original goals of the project certainly include a consideration for digital technology, but the main objective was to simple identify where (and if) the archives of these individual theatre companies across the country exist, and in what form and shape. This is a long-term, ongoing project, but I can not help to think on the day many years from now when a theatre historian might be able to find (and read, and, hence, perform) the archives from a theatre in Seattle from the relative comfort of her office in Atlanta. I am actually on the Baltimore team for this project, and I hope the digital component of our conversation can always be a part of our thinking as we work through our local archives in relation to the national project, as it has implications for both theatre practitioners and theatre scholars.

The other project is in many ways just a dream in the mind of one particular writer. Gwydion Suliebhan is a DC-based playwright and the DC representative for the Dramatists Guild. He does a lot of thinking and writing about making plays and getting them produced, and the state of playwriting and theatre in the mid-Atlantic and across the country. Back in February of this year he wrote an essay on his blog (with an abbreviated version over at HowlRound) about the need for technological intervention in the process of new play development and production here in America. I will not dive in to his entire idea here, but he suggests, basically, a national database of plays, uploaded by individual playwrights or their agents, and accessible to any theatre looking to produce said plays. This is all in hopes of ending what is quickly becoming an archaic, time-consuming, and one-way conversation of playwrights submitting copy after copy of their scripts to theatre companies, sometimes never to hear back from the theatre. Gwydion basically asks what would happen if we took that process and, using all of the advantages of digital databases, turned it on its head. This would be the performance of archives on a large scale. While the original and primary goal of this “New Play Oracle” would be to change the way theatres and playwrights communicate with each other, there are profound implications for scholars as well, who would be able to (if the user interface was designed for it) search the database in order to find answers to questions about the state of contemporary American theatre that they might never have been able to ask before.

Most playwrights, I feel confident saying, work digitally from the beginning of their process now, which changes the difficulty of encoding and interpretation of a playscript. However, the playscript for a play is not ever the only version of that play. Each production essentially produces its own script. What if there were a database that held, not just a new play as uploaded by a playwright, but also the promptbook of the stage manager from every production of that play? Or the accompanying set, lighting, and costume designs? Or the program and production notes? What if they were all encoded so that they were searchable? And there are countless other possibilities as well, including the notion of a play as video game (meaning, a play structured as a database where the audience must extract their own narrative).

It is easy to get carried away with grand ideas at this stage. But the larger point rings true – archives and databases, because they are performed, are not situated in opposition to performance and embodiment (and even liveness, which I did not get to touch on here), but rather in agreement with them, and are therefore possible tools (prosthetics, even) for theatre practice and scholarship. Our group encoding project of Mary Shelley’s manuscript made these ideas seem, not only obvious, but also practically inevitable. Taylor, in the above quotation, states that “by taking performance seriously as a system of learning, storing, and transmitting knowledge, performance studies allows us to expand what we understand by ‘knowledge.’” (16) I believe that statement can be extended to database and archives, and to the relationship of the two to performance and the performative.

For my final paper I am writing about fatherhood in Dracula and Frankenstein so first let me apologize for the fact that my head is entangled in those two books. That said, I was introduced to the film Silence of the Lambs (1991) for the first time a few weeks ago and something has been bothering me: Hannibal Lecter and Jame “Buffalo Bill” Gumb are fascinating recreations of Dracula and Frankenstein’s Wretch. Maybe this course and my paper have me seeing them everywhere, but I really think there is a case to be made. Further, how these two “monsters” relate to women.

Towards the end of the film, one of the cops asks Clarice Starling, “Is it true what they’re sayin’ [about Hannibal Lecter], he’s some kinda vampire?” She denies it and states that there is not “a name for what he is,” however, I disagree. I think vampire is a very good name for what he is. To begin with, vampires and Dracula (particularly in the screen adaptations) stand somewhere between male and female elements: they attract their victims with their elegant appearance and yet hypnotize with a powerful male gaze. Likewise, Hannibal Lecter, even in his prison clothes, is well groomed and dapper; his cell is more refined and elegant than those of the others and no cell-bars block him from view. He is meant to be viewed—especially when in the isolation cage in the center of the room towards the end of the film. In any other setting he would be appealingly put together; he looks at home in the refined suit at on the tropic island at the end of the film. However, within a prison, knowing the threat he poses, and under his dominating gaze that follows the camera, he is distinctly unsettling. Hannibal seems all the more dangerous because his danger is not overt.

Hannibal the vampire would seem to be dominant—his male gaze forcing Clarice to submit to him—yet, he never is interested in her submission. What Hannibal wants from Clarice is equality. For every piece of information he gives her he wishes stories of her life in exchange. Nor is he interested in consuming her—literally or metaphorically. When Hannibal escapes, he could easily target her but he makes the decision not to do so. Like Dracula with Mina, he seeks an exchange—not of blood, but of data. Interestingly, this suggests that so long as women are allied with the monster, they are safe—even humanized. Until Hannibal, none of the men in the film look at Clarice as an equal. She is an object.

Dr. Chilton says as much, “Crawford [Clarice’s superior] is very clever, isn’t he, using you? [….] A pretty young woman to turn him [Hannibal] on. I don’t believe Lecter’s even seen a woman in eight years. And oh, are you ever his taste. So to speak.” Further, the only thing Chilton seems interested in is not her ability to do her job or her life, but only her appearance: “You know, we get a lot of detectives here, but I must say I can’t ever remember one as attractive.” Even those she solicits for help, such as the students who study insects, help her mainly out of the hope that she might agree to go on a date with them as they find her physically, rather than mentally, appealing. Similar to Clarice, others see Hannibal only as an object. Dr. Chilton, whose care Hannibal is under, says of him, “Lecter is our most prized asset.” He is an “asset” and described as an animal and a monster, not a person.

Interestingly, Clarice is not endangered by the vampire of Hannibal Lecter, but by the objectification by Gumb and other men. Hannibal asks Clarice, “What is the first and principal thing he [Gumb] does? What needs does he serve by killing?” She replies, “Anger, um, social acceptance, and, huh, sexual frustrations, sir…” However, the answer Hannibal is looking for is “He covets.” He might just as well have been describing the motivations of Frankenstein’s Wretch. The Creature becomes a serial killer angry at his creator, finding no means of gaining social acceptance, and because Frankenstein denies him a mate. Granted, there is one major difference: the Wretch’s appearance is a visible example of his fractured self and his inability to fit in, while Gumb struggles to create an appearance that matches his fractured interior. Hannibal claims about Gumb, “Look for severe childhood disturbances associated with violence. Our [Buffalo] Billy wasn’t born a criminal, Clarice. He was made one through years of systematic abuse. Billy hates his own identity, you see.” Once again, the quote could just as easily be applied to the Creature whose birth is marred by his violent abandonment at the hands of his “father,” is made a criminal by years of abuse and loneliness, and who hates himself as much as he does his creator. Those things are what make him “savage and more terrifying” than Hannibal.

The danger represented by Gumb is clearest. He directs his attacks on women and openly attacks Clarice, as well. Gumb, though he identifies with women, thinks he can become one by literally creating a patchwork girl—or at least a patchwork girl costume. He thinks he can become a woman by putting on the skin of his female victims. Therefore, it is through mimicking the appearance of womanhood and not the experience of womanhood that he seeks to become female. Just as the other men, Gumb reduces women to appearance and not their identity. He ignores his victims emotions, pasts, and memories—the things which one uses to construct an identity. In fact, Gumb never refers to the women by name or even “she,” only as “it”: “It rubs the lotion on its skin or else it gets the hose again,” “yes, it will, Precious, won’t it? It will get the hose,” etc. In spite of Gumb’s desire to become a woman, he fails to recognize them as more than objects. He denies them status as people.

Her superiors don’t help matters. They inturrupt her training to send her into the field. They don’t listen to her arguments and consequently she walks into danger ill-prepared. In fact, the only reason Hannibal is able to escape is because the police focus on his exterior rather than his interior—they look only at the face of the “victim” and fail to recognize it as merely a fleshy mask (the face of one of his guards which he removed for the purpose). Thus, it’s clear that whether through Gumb or Clarice’s colleagues, objectification and exterior is what endangers women—and through the officer’s mistake, men, too—rather than the monstrosity of Hannibal. Perhaps because Hannibal is positioned between the male gaze and the feminine object to be viewed, he is able to use his objectification in the eyes of men to his advantage.

Hannibal is different. As frightening as it is, he is fascinated by Clarice’s mind. He explores her memories, fears, and background all in an attempt to know her. Even in his method of killing he is interested in the interior of his victims for he consumes them entirely, with particular interest in their interior organs. I wouldn’t go so far as to say Hannibal is a feminist hero—he does eat a nurse’s face, after all—but he is the lesser evil to Clarice and even proves a vital ally. Further, Clarice is undoubtedly the hero of the film. Though, even that is fascinating as it shows that to be a hero a woman must court a monster and be his equal, ally with him to combat the other, more dangerous monstrosity and one that cannot be courted because it refuses to recognize the heroines humanity. If Red Dragon is anything to go by, for a man to be a hero, he must become the monster he hunts. He must feel the monstrosity inside of himself. Clarice, need on prove her humanity to the monster as objectified as she is to empower herself. Through this, the two form a special bond. Hannibal, if teasingly, suggests, “People will say we’re in love.” Certainly the two share a common language, so to speak. Clarice is the only one able to decipher his anagrams and interpret the clues in his turns of phrase. As frightening as Hannibal is, he is the only one who understands her and sees Clarice as more than a tool to be used, an art object to be admired, or a vehicle for sexual pleasure. It takes a monster to give woman her humanity and a woman to see the humanity in the monster.

(Part 2 of a multi-part post. See Part 1 here.)

Words weave through sentences, submerge from view, resurface, resubmerge, warp and weft of weave or whatever metaphorical model we can throw at it. A word indexes many situations; a situation indexes many words. Can we see words and narrative, i.e. semantics and episodics, as orthogonal to one another, at right angles? Say, “story” is the X axis, “wording” the Y. Cognitive psychologists for a long time have entertained the distinction of semantic from episodic memory, and sought to discern whether they are, as hypothesized, truly independent from one another. Steven Prince, at al. (2007) report in Psychological Science that “the neural correlates of EE [episodic encoding] and SR [semantic retrieval] are dissociable but interact in specific brain regions.” In an example of this kind of interaction, semantic associations enhance the retrieval of episodic memories (Menon, et al., 2002). One site of interaction between the semantic and the episodic happens at the very instant a word is semantically integrated into a sentence, the very instance, in effect, when it enters into the telling of an episode.

While Swinney’s and others’ interest is pitched at an understanding of how we “compose” an interpretation out of a sentence’s building blocks, from the words and the grammatical relations within it, it does not seem to me to be too great a stretch to map this fine-scale event to the wider action of narrative within which it happens. Those ephemeral moments interest me when irrelevant meanings are sloughed away and only meanings fit to the flow of narrative within which they are embedded are left. This is the moment I have called “reading between the words.”

For every word we read, our mind opens and closes on that word’s potentialities, like the gate of a movie projector opening and closing the light on frame after frame of a film that slips a pull-down of filmstrip though, click-click-click in those interstices between openings, a sentence operating on our minds like a filmstrip operating on our eyes and visual cortices. By persistence of sense just as to the eyes, the film works by persistence of vision. Open, closed, open, closed—but it all comes coherent in a single stream, illusory yes, but to the mind, real. In fluent reading, whole gobs of text go in before consciousness opens its aperture. Flick-flick-flick. But it seems continuous.

William Nestrick, citing Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” states that “the film is the animation of the machine, a continuous life created by the persistence of vision in combination with a machine casting light through individual photographs flashed separately upon the screen.” Narrative, an older technology, is an animation of another machine. Our deeply naturalized habits of reading elide the composite, discontinuous nature of our construction of meaning. Like the animation of the machine, it invites comparison to the monster from Frankenstein—and hypertextual disruption, what Shelley Jackson encodes in Patchwork Girl.

In the prevalent “invisible style,” films build seamless scenes from successions of discrete shots much as the mind builds seamless sentence understanding out of successions of words. What is left out is simply not noticed. Maybe it is repressed or abjected—but to waking, normal cognition, something must be, because the entirety of the worlds we build in our minds arises from selectively attending to some things and not others. Repression in one sense is the inescapable flip side of being in the world with a mind. It is the flip side of the selective attention that gets knitted together by wetware magic into scenes and stories we assemble, recall, reform, tell, and retell. No word drawn from the batch of “non sequitur,” “relevant,” “irrelevant,” “emphasis,” etc. could bear on our way of writing and transacting communication if it were not in a context of narratives, stories, and episodes, with their characteristic features: topics, action, motivation…. And none of these concepts would have any utility to us if construction of stories in our minds were not inherently selective, if thought itself were not inherently so.

The process of selection and of assembly follows a pattern something like what Katherine Hayles describes in “Flickering Connectivities in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl” (2000). More than the signifier, though, it is signification that flickers, the association of signifier with signified, on a pattern of flickering consciousness, in which access to the results of the automatic, unconscious process of lexical access flickers in and out, in fluent reading seldom noticed. This kind of processing, highly automatized by skill, can be disrupted by divergence from conventional expectation. Since 1917, when Russian “Formalist” Viktor Shklovsky described it, this disruption of the automatic has been prominent in aesthetics, theorized as “strange-making” (ostranenie to transliterate the Russian), or “defamiliarization.” The practice has its precedent in the work of William Wordsworth. Explained by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his Biographia Literaria:

“Mr. Wordsworth, on the other hand, was to propose to himself as his object, to give the charm of novelty to things of every day, and to excite a feeling analogous to the supernatural, by awakening the mind’s attention to the lethargy of custom…”

In the frame of the present post, comparing the cognitive integration of text with the sensory integration of motion pictures, this would be akin to slowing the film down below the critical flicker frequency, so as to break the illusion. In the technoromantic frame, the mechanism of novelty’s action in the brain is the “orienting reflex,” first described by Ivan Petrovich Pavlov as the “shto eto takoi” (“what is it?”) reflex. The orienting reflex is the mechanism that breaks the automatic.

Hayles:

“In Patchwork Girl, one of the important metaphoric connections expressing this flickering connectivity is the play between sewing and writing. Within the narrative fiction of Frankenstein, the monster’s body is created when Frankenstein patches the body parts together; at the metafictional level, Mary Shelley creates this patching through her writing.”

Shelley Jackson’s work strategically disrupts narrative at several levels, from fine-grained lexical interactions to collisions between textual elements arising in the restructuring of narrative (as hypertext) and exploitation of a medium (the computer) that restructures the reading interface. Significant to this is Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto,” which treats the reconfiguration of the human form itself. Hypertext operates, for now, on the evolved biological capacity for cognitive reconfiguration, hacking the machine via its present interface.

What lies at the asymptote of narrative restructuring by hypertext? Where does it lead? Again sketching: At the outer extreme of hypertext is the “chaotic novel” described in “The Garden of Forking Paths” by Jorge Luis Borges. Any (coherent) narrative we read picks out senses of the words within it, biases us to read words one way and not another. So, if a narrative like the Garden of Forking Paths were to be realized—in which we visit every possible line of a story that unfolds within it—must we then also visit every possible sense of every word within it? Not just as we encounter them, in the way Swinney shows us is so often unconscious, but as we integrate them into their contexts? What happens if word senses themselves mutate with context, with the events that happen around them in the stories they enter in? What does representation of this level of complexity represent?

——————————————————————————–

Caveat:

I have assumed in this series of blog posts that what is happening at the lexical level in sentences is a microscopic instance of a larger sweep of events in our cognitive construction of narrative meaning—that the sentence in some sense works like the scene, and so on up. This theoretical portrayal is adumbrated, sketchy: conjectural. Reflexively, though not necessarily destructively, it is subject to the same form of critique, of illusory continuity. Delve into the psycholinguistic findings, and extend them, and expect the results to richen or complicate the present picture. A side-effect of reliance on Swinney’s work may be acceptance of a modular model of word representation in the brain, something others have inferred from it, with fully independent representations of word meaning. This may contradict “interactionist” models of sentence interpretation, which in my view are essential to understanding how we handle figurative language. For one form of experimental challenge to Swinney et al., see “Early Integration of Context During Lexical Access of Homonym Meanings,” by Janet Lee Jones in Current Psychology 10, no. 3 (Fall 1991): 163-181. For a theoretical consideration of lexical interaction in sentences, see “Should Natural-Language Definitions be Insulated from, or Interactive with, One Another in Sentence Composition?” by L. Jonathan Cohen, in Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition 72, no. 2/3 (Dec. 1993): 177-197.

—————————————————————————————

Works Cited:

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1964. “The Garden of Forking Paths.” In Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings, 19-29. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. 1983. Biographia Literaria. Ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 149-181. New York: Routledge. (Available online at: http://www.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/Haraway/CyborgManifesto.html)

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2000. “Flickering Connectivities in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis.” Postmodern Culture 10, No. 2.

Jackson, Shelley. n.d. “Stitch Bitch: The Patchwork Girl.” MIT Communications Forum. http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/papers/jackson.html

Jackson, Shelley. 1995. Patchwork girl, or, A modern monster by Mary/Shelley, & herself: a graveyard, a journal, a quilt, a story & broken accents. Watertown, Massachusetts: Eastgate Systems, Inc.

Jones, Janet Lee. 1991. “Early integration of context during lexical access of homonym meanings.” Current Psychology, 10 (3).

Menon, Vinod, et al. 2002. “Relating semantic and episodic memory systems.” Cognitive Brain Research, 13:261–265.

Onifer, William, and Swinney, David A. 1981. “Accessing lexical ambiguities during sentence comprehension: Effects of frequency of meaning and contextual bias.” Memory & Cognition, 9(3): 225-236.

Prince, Steven E. et al. 2007. “Distinguishing the Neural Correlates of Episodic Memory Encoding and Semantic Memory Retrieval.” Psychological Science, 18 (2): 144-151.

Swinney, David A. 1979. “Lexical Access during Sentence Comprehension: (Re)Consideration of Context Effects.” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18:645-659.

(first of a multi-part post)

“Thinking is conducted by entities we don’t know, wouldn’t recognize on the street.” –Shelley Jackson, “Stitch Bitch: the Patchwork Girl”

In “Stitch Bitch,” an essay about her hypertext novel Patchwork Girl, Shelley Jackson treats us to a succession of metaphors for embodiment and the way we read: The body is a “statue,” a “hard kernel.” Hypertext is “the banished body”; it sets up “rendezvous between words never before seen in company”; when it diverges at a choice-point it dissolves as “a Cheshire aftercat.”

Hypertext brings into action properties that lie dormant in conventional linear narrative. Jackson enumerates these properties in the section entitled “Collage.”

“We don’t say what we mean to say. The sentence is not one, but a cluster of contrary tendencies…. But nobody can domesticate the sentence completely. Some questionable material always clings to its members. Diligent readers can glean filth from a squeaky-clean one. Sentences always say more than they mean, so writers always write more than they know, even the laziest of them.”

Hypertext through its strategy of design activates those dormant meanings:

“It was not difficult, for example, to pry quotes from their sources, and mate them with other quotes in the ’quilt‘ section of Patchwork Girl, where they take on a meaning that is not native to the originals.”

To understand what Jackson hypothesizes to be happening in hypertext, it helps to understand the workings of the narrative style it would subvert. Conventional linear narrative, which Jackson describes as “fated slalom,” is configured so as to shepherd readers away from divergent threads: “Plot chaperones understanding, cuts off errant interpretations.” How narratives repress the penumbral interpretations that could emerge from them, how they tame the many voices of inherent allusion and come to sound like one voice or one story, how they filter their rich harmonies down to singular melodies, is far from entirely understood. At the sentence level, this resolves to a question of how a sentence’s prevalent meaning is composed out of words that are in themselves inherently polyvalent and ambiguous. Arriving at sentence’s end, we usually have an unequivocal idea of what we have just read. But how does the brain make meaning, word by word, as it reads a sentence? When—at what moment in the reading—have we dispensed with alternative interpretations, including the senses of words that don’t fit?

In a series of experiments beginning in the late 1970’s, psycholinguist David A. Swinney developed an innovative way to pinpoint the moment of word disambiguation in sentences. Swinney asked: As we are reading, do we access all of a word’s senses at once, and only then disambiguate them to fit the prior context, the flow of the sentence they occur in? Or, does the sentence we are reading, and our understanding of it, preselect what senses of a multivalent word’s meaning we perceive, so that we never even entertain irrelevant ones? At stake was an understanding of how verbal memory is organized, and whether word senses are accessed independently from sentence interpretation. Do we really have access to the “contrary tendencies” made possible by the breadth of allusion, and semantic potential, that its constituent words carry within them? We disambiguate words at some point; but when?

Swinney’s questions concern what psycholinguists call “lexical access.” To answer them, his group developed the ingenious “cross-modal priming task,” where one mode was auditory, the other visual, where listening to a soundtrack and reading from a screen could together be used to tease out the timing of disambiguation for words within sentences. In one experiment (1981), the auditory track plays a set of strategically constructed sentences, each with a carefully chosen word—let’s call it a target word–placed somewhere within it. That target word is in itself ambiguous, but the sentence is designed to support just one interpretation of it. At the same time, via the visual track, other carefully chosen words are flashed on a screen. The flashed words are, in fact, prompts that are semantically related to one or another meaning of the ambiguous target word from the auditory track. And all this takes place while the experimental subject engages in a psycholinguistic “lexical decision task” (LDT).

The experiment uses a series of sentences and target words, but as an example, let’s say the ambiguous target word is “scale,” and that two among its available meanings are: “a weighing device” and “a protective plating on a fish or reptile.” We can’t be sure which meaning is relevant until we hear it used in a sentence: “The postal clerk put the package on a scale to see if it had enough postage” vs. “The dinner guests enjoyed the specially prepared river bass, although one did get a scale caught in his throat.” You (the experimental subject) are asked to listen to one of those sentences read aloud as a soundtrack over headphones, but at the same time you have a task to perform: Watch a monitor screen and when a string of letters appears, just as quickly as you can, press a button telling whether it is a word or not . This is the “lexical decision task.” Ideally, when you see “Glmople” or “~!@#$%^&” you press the “no, not a word” button and when you see “breakfast” you press “yes, that is a word.”

For a long time psycholinguists have known that performance on the LDT can be facilitated, speeded up, if you have read semantically related words just beforehand. Swinney’s addition of the auditory track to the visually presented LDT enabled his uniquely time-sensitive measure of lexical access. Thus, using the ambiguous target word (e.g. “scale”) Swinney could flash related words on the screen and measure the time it took for people listening to that audio track to press the button for “yes” or “no,” “word” or “not a word.” He could probe with those visually flashed words to see which senses of “scale” were active in the listeners’ minds. All he had to do was to choose probe words to flash on the screen that were related more to one sense than the other, at any given moment. A probe word related to “scale” as “a device to measure weight” could simply be “weight,” then; and a word related to “a protective plating on a fish or reptile” could simply be “fish.” If there is priming—if hearing “scale” helps us to answer the LDT more quickly—then we can measure it.

Swinney found—contrary to earlier experiments by other researchers who had probed for lexical access only after the sentence was over—that at the moment the ambiguous word (“scale” again) was played on the soundtrack, multiple senses of that word were accessed.

That’s at the moment we read a word. How long, though, do all senses of a word remain available to us, after we read it? Swinney knew from others’ experiments that alternative meanings were unavailable by the time a sentence had been read. How long during sentence reading were alternative word senses available? Swinney’s second experiment was designed to provide an answer. Probing with the same sets of visually flashed words a second-and-a-half later, a second-and-a-half after the onset of the ambiguous word in the soundtrack, Swinney found the priming effect was gone. Only the probe words related to relevant senses of “scale” gave rise to a faster LDT while irrelevant senses that had been primed in the previous experiment were gone–knocked right out of the sentence interpretation. As Onifer and Swinney (1981) conclude, “In the absence of any strongly biasing context, it appears as though all meanings of a lexical ambiguity are accessed, at least momentarily. Such access is not available to conscious introspection, and the listener eventually becomes aware of only one of the meanings accessed for the ambiguity.”

Swinney has illuminated the cognitive processing that goes into reading within a small unit of narrative, the sentence. On this fine scale, his group’s results bear out Shelley Jackson’s descriptions of a conventionally linear “slalom” narrative, a narrative that does not invite attention to its inherent ambiguities. Each word arises in turn with its full multiplicity of meaning, only to be delivered to consciousness in a tightly narrowed sense that fits the sentence’s unitary whole. There’s a verbal sleight of hand in an unequivocal narrative that sluices the course of consciousness: It’s a magic trick. To disperse attention is to disrupt what happens between the words, before reading resolves into an unequivocal interpretation.

None of this is to say that we never access multiplicities of meaning within the “slalom” linear narrative, or that we cannot. It is simply a typical case, and subject to habits of reading as much as it is to the formulae of writing. What Swinney’s work shows is a particular instance where, as Jackson declares, “We don’t say what we mean to say. The sentence is not one, but a cluster of contrary tendencies.” Lexically, it inescapably is. Hypertext works to subvert and call attention to a multiplicity of meaning inherent in any text. Its point of intervention is that interstitial moment when we are at the business of unconsciously sloughing away meanings that fail to fit a larger frame of narrative, where we are reading, literally, between the words.

(Part 2 is here.)

The Code, the Canonical, the Communist, the Commonplace:

Posted by in Spring 2012 | Uncategorized - (1 Comments)I.

I’ve talked in part about my experience coding the Frankenstein manuscripts, at least from a practical, project-oriented viewpoint, but there seems to me something lost in only talking about that side of things. While step-by-step instruction for a coding-based project like ours is certainly useful information in one sphere, it inevitably leaves out the impetus, the drive, the sheer imaginative hook, that got us roped into such a thing in the first place.

Something there is that doesn’t love the non-canonical: the marginalized, the deleted, the abjected, the notes and writings that never quite make into a final manuscript. This accounts for our fascination with celebrity interviews and bonus footage on DVDs, with directors’ cuts and ‘never-before-seen’ acting spots–and in the literary world (though much less glamorous than the film industry) it accounts for our desire to read the biographies of our favorite writers, to mine their drafts, letters, manuscripts, and notebooks, for glimmering bits of data that might, on one level, satiate our personal fan-boy appetites, and, on another level, serve as keys to unlock, inform, or explain our scholarly impulses and queries.

It’s a curious thing, this love of outside material, one we often pretend to not have (“death of the author,” ad nauseam) but, in the end, wear like chocolate on our faces.

My (detailed) experience as a novice encoder. I had no prior experience with programming before this project.

Getting Started

I wouldn’t have been able to start without the Digital Humanities boot camp or the first group meeting, where I was able to set up Oxygen, my account on github.com and download and install the Github client for Mac. In spite of that, when I was working on my own, I experienced technology anxiety, which I describe as unease caused by the various new programs required and fear that all of those elements would not become coherent. There was a slight error when my Github client was downloaded, the sg-data files downloaded to my documents folder which caused a moment of panic when I couldn’t find them. I soon realized that because this sense of unease was simply a part of the project. As I worked, the project did become coherent, but there were issues along the way. The majority of the work was learning the encoding language, which was precisely like learning a new language. When I was unsure of how to encode an element, because I am a novice, the SGA Encoding Guidelines didn’t always answer my questions—the answers were certainly there, but the explanations did not always make sense to me. Our team’s extensive Google document answered many of my questions and I was thankful that this was a collaborative project.

Markup Process

When doing the markup, I would start by looking at the manuscript image to get a feel for the elements of the page. Some pages were fairly “clean,” meaning there was not a lot to include in the markup besides transcribing the words on the page. The bulk of the encoding, for our purposes, focused on cross outs. I also liked to start by looking at the manuscript to keep the spirit of the project—the manuscript itself—as the focal point. I did utilize the Frankenstein Word Files (transcriptions of the text of the manuscript) and these files were invaluable. Deciphering Mary Shelley’s handwriting would have at least doubled, if not tripled the amount of time the project would take and I’m not sure that I always would have be able to make logical sense out of the words in the manuscript images. That being said, I would still check the transcription page against the manuscript image. I think the most challenging aspect of the markup was learning the necessary tags, especially as the tags continued to evolve. The tags became easier as the encoding progressed because they became more familiar. While encoding, there were also questions of specificity—encoding is meant to capture what is on the manuscript page but how detailed that can and should the markup be? When a cross out appeared, the encoding was marked by: rend=”overstrike” but that is not a particularly descriptive tag. There were variations in the cross-outs that the tag did not describe for example, one that used three diagonal lines, or one with two horizontal lines. I had a few pages with a fair amount of marginal text and I initially struggled with how I would properly encode an instance such as: the marginalia was aligned with lines 3, 4, 5, for example, it might actually all be part of line 2. That turned out to be too specific for our purposes, but it still seems like an important thing to note. I also wondered how important it is to describe the non-text elements of the page such as inkblots, when the handwriting was clearer or less clear (not illegible—there were instances when it seemed neat or messier), when the quill had fresh ink or, how best to describe those doodles, and et cetera. Many of these concerns seem subjective, the doodles especially so, my way of seeing a doodle may be very different from the way another person would view it. It does not seem accurate to leave these elements out, but it seems their level of importance depends on what the goal of the encoding is. I also noticed that I had to resist the temptation to act as an editor by fixing spelling or grammatical errors. It seemed odd to transcribe misspelled words, but I had to accept that my role was not that of an editor.

Some frustrating aspects of the project:

For all the initial difficulty of learning the markup language, the encoding seemed stress-free when compared with the frustrating technological issues The schema did change as the project went along, but that was more something I had to be careful to pay attention to than actually frustrating. One of the first issues was when the document(s) wouldn’t validate in Oxygen, which was required in order to push them to GitHub. I didn’t know the language of Oxygen well enough to know what caused the problem, which made it difficult for me to fix on my own. Fortunately, I could consult my group and found that sometimes, a < need to be moved to a different line. I think an encoder would need more experience with Oxygen in order to troubleshoot effectively. Other than the validation issue, Oxygen was relatively straightforward. My main frustrations were with the Github client for Mac—there was an issue where the client would not allow me to push the files I worked on, instead it wanted me to push every file in the sg-data folder. I know that other people experienced this issue and I do not know the exact cause, only that the experienced encoders at MITH thankfully fixed it. This seemed like a culmination of my technology anxiety—it seemed as if my encoding might be altered permanently or lost all together. My fears were not realized, and might be easily alleviated if the issues with the Github client could be eliminated.

The “emotional side”

The most rewarding aspect of the project was working closely with the manuscript images. I know the images were digital copies, but that did not prevent the experience from being thrilling. In fact, when I first looked at my ten pages, I felt a shiver of disbelief and awe—I was looking at the actual manuscript of Frankenstein! I did not think it were possible for anyone but scholars of the manuscript to have access to it. In addition to the thrill, I also felt closer to the text. What I mean is, I think there is often a distance between the author and the readers, especially when the author lived in a previous century, and this can turn authors into figures of isolated and independent genius. It is sometimes hard to appreciate that their writing reflects the real struggles of their times if the authors themselves do not seem as if they had been real people. I admit to feeling this way about Mary Shelley and seeing the spelling, grammatical errors, as well as the various cross-outs and changes in the manuscript made her seem more human. This also allowed me to feel closer to the manuscript—I could appreciate that it had been a fluid piece of art in progress, rather than the permanent finished project it appears to be when reading the novel. Though Frankenstein is likely not in any danger of being forgotten, digital encoding could be wonderful way to bring attention and appreciation to neglected texts.

Questions and thoughts for the future:

I wondered if it matters how much familiarity an encoder has with the text? I found that having familiarity with the novel made the process easier because I never felt lost in the text. I think encoding a text I had never read before, especially if it were an isolated 10 pages like in this project, would have been extremely difficult. I came to the conclusion that familiarity with the text is necessary if not completely crucial. If this is accurate, then it seems ideal that students of literature also be trained in encoding.

Thoughts on how to develop the tags further

My sense is that there should be one standardized markup that is perhaps closest to resembling the physical page of the manuscript in that it captures all of its elements. I wonder if there is a way to make a standardized mark-up—can any two (or more) encoders ever completely agree on what precisely needs to be included? I think it is possible to reach an agreement (through on on-going process) and from there, individual researchers could do their own encoding work and create tags for monstrosity, for education, for women’s issues, for anything a researcher would look for in Frankenstein. This might create many versions of encoding the novel, but the versions could be used as a tool for analysis.

My suggestions for change

Our group was fairly large and while the discussions via the GoogleDoc were invaluable, I think more face-to-face interaction and/or smaller groups, along with some in-person encoding might prevent going astray in the encoding and alleviate of the frustrations with the software. When we worked in our quality control checking groups (I worked with two other group members) it seemed like an ideal dynamic, we could easily check each other’s files, meet in person, and carry-on an email correspondence. As for the technology anxiety, I’m not sure that anything can be done about that besides gaining experience and perhaps a software change (likely beyond our control) to the Github client for Mac.

Before this project if I had any thoughts about how digital archiving was done, I would said it was just a matter of storing the manuscripts digitally. While it is important to preserve manuscripts digitally as well as to allow a larger audience access to them, this would not require a specialized language. I see the special language of textual encoding as a way to engage a text, to describe and analyze it while preserving it. This adds a richness and depth to literary study and analysis while also keeping literature current. I understand that there are powerful digital ways to study literature that I was admittedly ignorant of before this class.

The encoding project finished, let me first say: I greatly enjoyed the experience. When we were first introduced to encoding in class during boot camp, the experience was rather intimidating. I had prior experience with programming, but creating a program is different from describing through code. However, it did at least give me an advantage of knowing that all tags once opened (like <line>) needs to be closed (with a </line>). But, as with most things, what one already is familiar with may make things easier, nevertheless it is the differences one must learn makes a project exciting.

While intimidating, learning to describe the manuscript pages in code made them personal. My chief source of delight was also my greatest challenge when it came to encoding: Mary and Percy’s illustrations and flirtations in the manuscript. I’ve discussed this in my submission to the group post so I don’t want to discuss the technical aspects of this, but rather the reason why it deserves to be encoding. It humanizes them. One has a tendency of thinking of great and famous writers as something unlike us—not monstrous, but at least a sort of other. No matter how human we know them to be, how much they celebrate that themselves, they still feel distant.

In one moment, looking at the tiny sketch of flowers in the margin of the text, one suddenly relates to these long dead writers. We form a connection because of the sheer humanness of these little marginalia. Percy and Mary have become people who, perhaps in a moment of boredom or when searching for inspiration, begin to draw doodles of nature in the corners. And Percy, who writes at the end of the page, “O you pretty Pecksie!”, we are reminded is a husband—one who flirts with his wife while editing her manuscript!

But why is this important? Maybe it isn’t and maybe one just records it because it is there, yet I disagree. I think it’s important because it stops us and reminds us to be moved by what we read. It reminds us—here, I think of our discussion in class—that these distant authors are not others, but us. WE can relate to them as much as we relate to their writing. They too fully experienced and understood the human. That I think is very important and that is why even those details, unimportant to the text, are still important.

The (Post)Humanist Matrix, Neuromancer, and Cyberpunk

Posted by in Spring 2012 | Uncategorized - (0 Comments)Reading Neuromancer for the first time has, quite predictably, drawn me back to The Matrix. I have some familiarity with the cyberpunk genre (Snow Crash is one of my favorites), but Neuromancer reminds me even more just how many elements The Matrix borrowed from the genre, presumably in order to subvert it. And yes, this includes the term, “the matrix” itself, jacking in, Zion, the mirrored shades, and a lot more

As we discussed, The Matrix acts as a response to Neuromancer’s apparent indifference towards or even acceptance of posthumanism. While in The Matrix, the question on everyone’s mind is, “What is real?”, that question just doesn’t seem to matter in Gibson’s novel. Moreover, the question of what it means to be human is much more complicated in Neuromancer. Try contrasting Molly’s artificial mirrored lenses, not to mention her razors, with the plugs built into the humans of The Matrix. While in the novel, these “augmentations” largely viewed as positive, if a little creepy, enhancements of the self, the plugs in The Matrix are viewed as less than human, especially when compared to Tank and Dozer’s “homegrown” humanity.

You could argue that Molly’s augmentations arise from her own free will (as far as we know), while the plugs in the film only allude to the humans’ slavery to the machines. I wonder, then, whether any attempts have been made in the world of The Matrix to remove these plugs. If it were even possible, you could imagine some clinic in Zion dedicated to bringing Matrix-free humans back to humanity.

I may have contradicted my own point a little, but you definitely get the sense in Neuromancer that posthumanism is a reality whether you like it or not, while in The Matrix you see the characters fighting against this notion and turning back to the idea of an authentic humanity. Case, whose drug addictions almost cost him his life, is rewarded by the end of the novel with new organs, so he can continue altering his consciousness without consequence. Who benefits the most in the end? Wintermute! And you’re left unsure whether this is a good thing or a bad thing. But Gibson might argue that this is beside the point.

I could go on and cite all of the instances in which The Matrix emphasizes its humanist agenda, but we’ve discussed this in class already. Instead, I’d like to return to Neuromancer by focusing on the ways in which the Wachowski brothers’ film continues to borrow elements of the novel, even going so far at times to contradict, or complicate, its own definition of humanity. In other words, as much as The Matrix works in reaction against the postmodern, posthuman, cyberpunk genre, at times the film inadvertently supports the claims it tried to reject.

From the outset, the characters as well the audience privilege the unpleasant natural over the pleasant artificial simply because what is real matters to us. We reject the machines, then, as constructs rather than natural beings. And, of course, we reject the Matrix itself as an illusion, as opposed to the reality of the real world.

At times, however, the film complicates this value system by presenting the artificial as having clear advantages over the real. This shouldn’t surprise us, as Morpheus and the others work within the Matrix in order, presumably, to one day dismantle it. As Kathryn has already suggested, however, the end goal might not even be possible. By bending and breaking the rules of the Matrix better than the Agents, is Neo affirming his humanity, or only that he is a better machine than the machines (“you move like they do”)? As Tank downloads all of the combat training programs into Neo, he remarks, “He’s a machine.” What are we to make of this?

And then there is Agent Smith, whose own path in the second and third films mirrors Neo’s in many ways. In Baudrillard’s terms, if Neo is the remainder, Agent Smith is the subtraction of that remainder into reality (or is it the other way around?). As Neo’s story progresses, he sees more and more that Agent Smith is right: the only thing that matters is purpose. By submitting to fate, is Neo asserting his humanity, or is he admitting that human or machine, we are all programs with built-in purposes?

And then there is the fact that by the end of the third film, even after the war, the Matrix still exists. If Morpheus says in the first film that “as long as the Matrix exists, the human race will never be free,” why is everyone celebrating? Maybe because this compromise is the best deal humanity will ever get. As much as Neo and company despise the Matrix, they work pretty well within it, and it becomes essential to all of their schemes and eventually brokering a deal for peace in the end. So, I ask, is The Matrix a posthumanist work after all? For all of its privileging of an authentic humanity, the film casts Neo in the role of a machine, while giving human motives to Agent Smith. I wouldn’t go too far with this argument, but you can see that while The Matrix seemingly reacts against Neuromancer’s acceptance of posthumanism, a few of these ideas carry over after all.

(Note: Poor attempt at a meme. Photograph of Trinity, quote really by Molly, misattributed to Y.T. from Snow Crash).