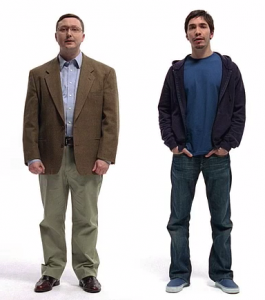

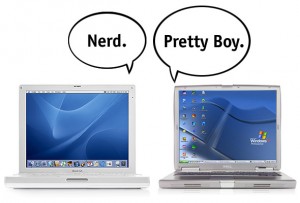

As Technoro Team MARKUP’s sole Windows user, it was clear from the start that “lack of cool” would not be my only hindrance during the beginning phases of the project: our team’s software set-up instructions were geared towards the Mac user, and included a Mac-specific streamlining program, GitHub for Mac. As the GitHub for Mac site chirps brightly, “When you first launch GitHub for Mac, we’ll help you set up your GitHub account and find repositories already on your computer. From there, you can start managing repositories.” In short: we’ve got you, brother!

Well, not so much help from GitHub, I found, if you are the aging, brown-suited, fuddy-duddy PC guy. At the end of the day, Git is just not fully supported by Windows. This does not mean that PC users are precluded from the project work; the software infrastructure setup — and support thereof — is just chunkier, slower, and the components are less condensed. In fact, anticipate an agonizing project acceleration rate: of my total project time investment, approximately 60% was spent on initial techno-troubleshooting, with only 40% on actual TEI markup.

GitHub for the PC User is distinctly less program-supervised, involving multiple user steps and several separate components, including the GitHub website, GitBash and GitGUI. From the position of a complete command-line newbie, the GitHub Guide does not sufficiently hand-hold overall – “wait, that command saved what where?” – but does include a subsection called the Windows Setup Guide, located here: <http://help.github.com/win-set-up-git/>

In hopes that my notes may help streamline the Windows set-up process for future users, the essential components of the Git setup process – in the context of our markup project purposes — are outlined here in “newbie-speak”:

1) GitHub.com

This is where the games begin, and where I found myself revisiting often in order to access others’ file changes, view changes to the repository (or, “repo”), and perform other repo-related tasks.

Setup Phase One, Step One is to visit GitHub.com and download the Git Setup Wizard, which unpacks both GitBash and GitGUI into a specified folder. You will return to this site after you generate a new “SSH key” in GitBash, as follows:

2) GitBash

GitBash is, well, a Bash prompt – think Windows Command Prompt – with access to Git. It is here that a user may run commands to various ends. Specifically, for Phase One, Step Two, the user will want to get that SSH key generated and copy it in back at GitHub.com. In short, GitHub will “use SSH keys to establish a secure connection between your computer and GitHub,” and this process, sufficiently outlined in the Windows Setup Guide, involves three sub-steps: 1) checking for already-existing SSH keys, 2) backing-up and removing any found, and 3) generating a new SSH key. At this point, you will create and enter a pass phrase. Be wiser than this user, and note this pass phrase.

Phase One, Step Three: Also from GitBash, you will set up your Git username and email (to be used on GitHub.com, as well as certain administrative tasks on GitBash). Again, the GitHub Windows Setup Guide proved easy-to-follow for this step.

Once set with Git login details, it’s on to Phase Two: Forking, which can be done fairly simply back at GitHub.com (in short, click the “fork“ button in the repository you wish to access). However, there is a following action, which is to clone this repo locally. Remember, Git is a “revision control system”: therefore the meta-process is 1) clone data so that you can 2) edit select data and then 3) upload changes that will be reviewed before being processed onwards. This was a sedating thought in the midst of command prompts, file paths, keys, and forks: oh, right…there is a greater purpose here.

So, to “clone the repository” (rather, to make a local copy of the repo of XML files in which we type out our markup, and which the system will push back to the master branch from later), we run a cloning code in GitBash, followed by one last code (in truncated form, “remote add upstream”, then “git fetch upstream”) that changes your default remote from pointing to “origin” to the original repo from which it was forked. And, here is where you will likely need to wield that pass phrase from Phase One, Step Two.

Once forked, all infrastructure is in place for the user to return, or push, all edits into the repository, for team access through GitHub.com, review and further process.

Where and how to properly access the schema file [containing the coding “rules”] remains a mystery to me: our team leader kindly emailed me the “Relax NG Compact Syntax Schema” file, which had to remain where saved (for me, my Desktop) in order to be recognized by another product, not a part of the Git package: the Oxygen XML Editor.

3) Oxygen XML Editor

Perhaps the most user-friendly of all components, the Oxygen XML Editor is where the PC user can shake off her bewilderment with Git and let the bewilderment with TEI markup begin! Oxygen allows for multiple XML files to be opened simultaneously as tabs, and if your schema is properly in place, the “Validate” feature provides feedback on any exceptions or errors you’ve entered. Just be sure to *save* each file after any changes; moreover, be sure to save in the cloned directory (for example, mine defaulted to “Jennifer Ausden/sg-data/data/engl738t/tei“) not to your desktop, or else GitHub.com cannot locate your changes to the files, and the push process will essentially be doomed. Speaking of uploading doom…

4) GitGUI

GitGUI, while part of the original download bundle, was utilized only when I was struggling to push my Oxygen XML files – at least, those containing any changes since the last push or since the original clone, as the case may be – back to the repo at GitHub.com.

When I tried running in GitBash the Windows Help Guide’s command “git push origin master”, I was met with a nerve-shattering error message:

|

Pushing to git@GitHub.com:umd-mith/sg-data.git

To git@GitHub.com:umd-mith/sg-data.git

! [rejected] master -> master (non-fast-forward)

error: failed to push some refs to ‘git@GitHub.com:umd-mith/sg-data.git’

To prevent you from losing history, non-fast-forward updates were rejected

Merge the remote changes (e.g. ‘git pull’) before pushing again. See the

‘Note about fast-forwards’ section of ‘git push –help’ for details.

|

The thought of “losing history” inspired an immediate chai latte break, but upon return, I warily entered the command for ‘git push –help’, whose advice brought with it another surge of fear. In a nutshell: this “fast-forward error” is likely happening because someone else is attempting a simultaneous push. Wait if you can, but if all else fails, go ahead and add “–force” to the end of the code. DO NOT force a push unless you are absolutely sure you know what you’re doing.

Failing to meet that criteria, I had a brief moment of panic, and decided to implement my own local version control: first by attempting to move “my” assigned XML files from the cloned repo folder to a local folder, until I realized the push could not happen from another folder than the original cloned location. Local version control, Plan B was to create a surrogate system; namely, a highly sophisticated JIC process (…that is, emails to myself of the XML files containing my code, “Just In Case”).

Thus feeling fairly secured – for some reason – my next step was a test work-around, by switching over from Bash to GUI. The latter, upon opening, offers three options: “Create New Repository”, “Clone Existing Repository”, or “Open Existing Repository.” In confidence I had (probably) cloned sufficiently at this point, I chose to “Open”, successfully “opening” C:/Users/Jennifer Ausden/sg-data/ . This interface was much more friendly; here was a little window of “Unstaged Changes” in the helpful form of a file-path list (for example,“data/engl738t/ox-ms_abinger_c57-0022”) which with simple clicks allowed me to “Stage,” “Commit,” and finally “Push” back to the master branch and repository.

Heart racing, I flew back to the repository on GitHub.com, and lo and behold, there at [sg-data / data / eng738t / tei] were all the files (specifically, “ox-ms_abinger_c57-0022″ through “ox-ms_abinger_c57-0031″) to which I had made and saved a change.

Huzzah! Scores of emails and help searches later, the brave little PC was now equipped with:

1) a secure connection to GitHub.com;

2) a GitHub.com username and password;

3) a “fork” in the repository at GitHub.com;

4) a local, cloned version of the holding-place for all the empty XML files, to be filled with our markup coding magic via Oxygen;

5) the Oxygen XML Editor program in which to type up the code for each file;

6) a copy of the schema file, so Oxygen could properly “Validate” each file; aka, alert me to any coding incompatible with the schema, and;

7) through Git GUI, a way to push back my changes to the repo on GitHub.com.

And so it appears, Windows users can eventually function in, and contribute to, a team Git project. Just anticipate being, at least at start-up, the old Windows guy in the brown suit.