Gothic Horror and the Body

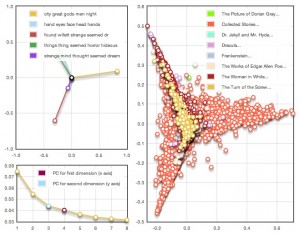

Posted by on Monday, April 23rd, 2012 at 9:28 pmSome of our Horror texts took a bit longer than expected to load. But when they came, I threw them all up through Woodchipper at once and I noticed some very interesting overlay of topics.

The classic “Horror Topic” (things, thing, seemed, horror, hideous) almost overlaps the topic related to parts (hand, eyes, face, heads, hands).

What could explain the overlap?

Is horror linked to the body in an integral way? Does the proximity of “horror” words to “body” words indicate a fear that is linked to the body? Or could it be indicative of bodily monstrosity? Basically, do these results indicate a fear of the body or a fear for the body? Or are characters using their bodies to sense fear?

To investigate I pulled out a selection of the paragraphs that fell in the upper left of the chart, those which scored highly in “horror” and “body parts.” I ran the chipper several times, with the texts in different orders, to make different novels sit on top, so I could get at them. I pulled out examples from eight different texts. Then I went through the paragraphs and bolded the words that I suspected put them into the horror category. I italicized the body parts. This way I could see for myself the proximity of horror words to body parts.

(My choice of words is certainly subjective. Another scholar might categorize differently. I’m not certain I match Woodchipper either. I didn’t, however, have any trouble finding either type of word in any of Woodchipper’s selected paragraphs.)

Here’s what I found:

Frankenstein (84-0242)

Mary Shelley (1818)

Urged by this impulse, I seized on the boy as he passed and drew him towards me. As soon as he beheld my form, he placed his hands before his eyes and uttered a shrill scream; I drew his hand forcibly from his face and said, ‘Child, what is the meaning of this? I do not intend to hurt you; listen to me.’

The Works of Edgar Allen Poe (2148-0456)

Edgar Allen Poe (1850)

There was an instant return of the hectic circles on the cheeks; the tongue quivered, or rather rolled violently in the mouth (although the jaws and lips remained rigid as before;) and at length the same hideous voice which I have already described, broke forth:

The Works of Edgar Allen Poe (2148-0205)

Edgar Allen Poe (1850)

I sat erect. The darkness was total. I could not see the figure of him who had aroused me. I could call to mind neither the period at which I had fallen into the trance, nor the locality in which I then lay. While I remained motionless, and busied in endeavors to collect my thought, the cold hand grasped me fiercely by the wrist, shaking it petulantly, while the gibbering voice said again:

The Woman in White (583-2109)

Wilkie Collins (1859)

“How do you know?” she said faintly. “Who showed it to you?” The blood rushed back into her face—rushed overwhelmingly, as the sense rushed upon her mind that her own words had betrayed her. She struck her hands together in despair. “I never wrote it,” she gasped affrightedly; “I know nothing about it!”

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (42-0086)

Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

“O God!” I screamed, and “O God!” again and again; for there before my eyes—pale and shaken, and half-fainting, and groping before him with his hands, like a man restored from death— there stood Henry Jekyll!

The Picture of Dorian Gray (174-0251)

Oscar Wilde (1890)

The suspense became unbearable. Time seemed to him to be crawling with feet of lead, while he by monstrous winds was being swept towards the jagged edge of some black cleft of precipice. He knew what was waiting for him there; saw it, indeed, and, shuddering, crushed with dank hands his burning lids as though he would have robbed the very brain of sight and driven the eyeballs back into their cave. It was useless. The brain had its own food on which it battened, and the imagination, made grotesque by terror, twisted and distorted as a living thing by pain, danced like some foul puppet on a stand and grinned through moving masks. Then, suddenly, time stopped for him. Yes: that blind, slow-breathing thing crawled no more, and horrible thoughts, time being dead, raced nimbly on in front, and dragged a hideous future from its grave, and showed it to him. He stared at it. Its very horror made him stone.

Dracula (345-0352)

Bram Stoker (1897)

She shuddered and was silent, holding down her head on her husband’s breast. When she raised it, his white nightrobe was stained with blood where her lips had touched, and where the thin open wound in the neck had sent forth drops. The instant she saw it she drew back, with a low wail, and whispered, amidst choking sobs.

Dracula (345-0968)

Bram Stoker (1897)

There on the bed, seemingly in a swoon, lay poor Lucy, more horribly white and wan-looking than ever. Even the lips were white, and the gums seemed to have shrunken back from the teeth, as we sometimes see in a corpse after a prolonged illness.

The Turn of the Screw (209-0168)

Henry James (1898)

My lucidity must have seemed awful, but the charming creatures who were victims of it, passing and repassing in their interlocked sweetness, gave my colleague something to hold on by; and I felt how tight she held as, without stirring in the breath of my passion, she covered them still with her eyes. “Of what other things have you got hold?”

Collected Stories (31-0690)

H. P. Lovecraft (2006)

Then, after a short interval, the form in the corner stirred; and may pitying heaven keep from my sight and sound another thing like that which took place before me. I cannot tell you who he shrieked, or what vistas of unvisitable hells gleamed for a second in the black eyes crazed with fright. I can only say that I fainted, and did not stir till he himself recovered and shook me in his frenzy for someone to keep away the horror and desolation.

Collected Stories (31-3241)

H. P. Lovecraft (2006)

The dreams were meanwhile getting to be atrocious. In the lighter preliminary phase the evil old woman was now of fiendish distinctness, and Gilman knew she was the one who had frightened him in the slums. Her bent back, long nose, and shrivelled chin were unmistakable, and her shapeless brown garments were like those he remembered. The expression on her face was one of hideous malevolence and exultation, and when he awaked he could recall a croaking voice that persuaded and threatened. He must meet the Black Man and go with them all to the throne of Azathoth at the centre of ultimate chaos. That was what she said. He must sign the book of Azathoth in his own blood and take a new secret name now that his independent delvings had gone so far. What kept him from going with her and Brown Jenkin and the other to the throne of Chaos where the thin flutes pipe mindlessly was the fact that he had seen the name “Azathoth” in the Necronomicon, and knew it stood for a primal evil too horrible for description.

Collected Stories (31-3201)

H. P. Lovecraft (2006)

That night Gilman saw the violet light again. In his dream he had heard a scratching and gnawing in the partitions, and thought that someone fumbled clumsily at the latch. Then he saw the old woman and the small furry thing advancing toward him over the carpeted floor. The beldame’s face was alight with inhuman exultation, and the little yellow-toothed morbidity tittered mockingly as it pointed at the heavily-sleeping form of Elwood on the other couch across the room. A paralysis of fear stifled all attempts to cry out. As once before, the hideous crone seized Gilman by the shoulders, yanking him out of bed and into empty space. Again the infinitude of the shrieking abysses flashed past him, but in another second he thought he was in a dark, muddy, unknown alley of foetid odors with the rotting walls of ancient houses towering up on every hand.

Conclusions

After mucking about in the paragraphs of these different texts, categorizing words, I don’t think my questions can be answered easily, nor do I think the link between body and horror can be simply explained. On the surface, it often seems that the characters are using their bodies to sense and to express their horror. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. Rather, it seems that the most intensely horror-filled passages contain a heightened consciousness of body and there must be more behind that body-consciousness. Whether this proximity of horror words to body words indicates horror of the body, or horror for the body would take further analysis and interpretation. I suspect that the answer lies tangled up in both options.

Monstrosity of the body is certainly an important factor in the Gothic Horror—that’s not a shocking find. Perhaps Woodchipper has failed, in this instance, to teach me anything that I didn’t already suspect. I do think the assortment of paragraphs identified by Woodchipper would give me a great place to start a more intense investigation.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.

The quotes looked prettier offset as quotes, but I lost my italics that way, which wasn’t worth it.

This would probably complicate your inquiry, but your research made me wonder about the connections between horror and the mind (a subset of which could be horror and emotion) and see how it intersects with monstrosity of the body–is there a corresponding monstrosity of the mind? I suspect so, but I wonder how closely to two are linked in literal and thematic proximity in a particular novel and in the larger Gothic genre. It seems as if Woodchipper leads to productive, if sometimes obvious, avenues of inquiry!