When I called my parents the week of the DH Bootcamp, I casually dropped the fact that I had gotten an introduction to XML:

“Oh, that’s just a mark-up language,” my dad said.

Just? Okay, granted, both of my parents know a little bit about computers (and by a little bit, I mean that computers and coding have been their careers since the 90s), but perhaps they did not comprehend that it was the English major son, not the son majoring in computer science, that was speaking to them.

But in any case, the introduction to encoding I had received was a bridge between my literary world, and the world of the rest of my family. XML evoked an uncanny feeling in me. I had a sense of what I was looking at. I had been raised with computers and discussions of data, server admins, C++, Javascript, etc. But why was I seeing it in an English class? Didn’t I change majors in undergrad. to avoid this sort of thing?

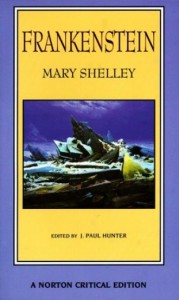

Well, perhaps the different perspective was what I needed to find some interest in the digital world. Textual encoding was appealing because it was an intimate engagement with the text (the text being Frankenstein) without the pressure of close reading; I was not struggling with the text, the text was letting me read it. I was carefully combing the text, multiple times really, between the manuscript pages, the transcription, and the lines text I was actually tagging. Rather than searching for nuances of meaning, I was looking at what was there, and what had been there. I felt privy to some information that not many have ever gotten the chance to see, and I was making the decisions on how all of it was to be understood.

“How it was to be understood”…That is a pretty empowering thought when your simply typing del rend=”strikethrough” around the majority of things you find worth tagging, but it is nonetheless an important idea to consider in how someone encoding a text should think. Are encoders the next generation in the line of editors and annotators of texts? Do they fulfill the same function, and do they possess the same responsibilities?

That is difficult to answer, but my short time spent encoding Frankenstein has given me some basic thoughts:

The Rabbit Hole:

Anyone trying to annotate, edit, and generally find meaning in a text is subject to the problem of the infinite amount of information that can be collected and juxtaposed with the text. For the encoder: what gets tagged and what gets left out? Since I was not involved in deciding the rules of the schema, fortunately, many of these questions were answered before I even thought of them.

The sic tag was the earliest incarnation of this issue. As I understand it, using this tag means the encoder finds a flaw in the manuscript. An editor, of course, will want to change and “correct” it, but an encoder? Well, are we not being more “faithful” to the manuscript by allowing its imperfections to remain? And then, what, if the tag were to remain, could be tagged with sic? Just misspellings? What about variations in place or character names, if they occurred? Can the sic tag be incorporated into a larger family for mistakes and irregularities, associated with tags for stray marks, doodles, or notes that are not part of the novel’s text? What would this family of tags be accomplishing in pointing out and subsuming all of these phenomena under the same rule?

A situation like the one above is why I find myself relieved to not have make decisions regarding the schema, and furthermore in not having to use the sic tag at all, due to the preference for a more “faithful” rendering of the manuscript. But of course, even considering the idea of what it means to be faithful to the manuscript opens up another potentially endless pathway and is another issue altogether.

A less dangerous path, however, that does open up in this line of thought is the temptation that encoders and editors both face in engaging with their texts: enforcing their views onto the text and to the readers.

Encoding Neutrality?:

When reading texts in, say, a Norton Critical Edition, there is the risk that the editor may influence a reading of the material. The footnotes may contain allegorical interpretations, strained connections to other texts, or pure assumptions on the editor’s part, and these can mold the mind of the reader in a particular way.

Encoding, I see, can run the risk just as well. If one were tagging allusions in Frankenstein, one might start with allusions to Paradise Lost, the foundational text of the monster’s language acquisition and the text that affects his perception of his place in the world. An encoder may decide to tag quotations, echoes, or parallel events between the two works, but in doing so, could be considered as going too far with their interpretation. A reader utilizing the encoded text would be fed the tagged allusions and echoes, and thus form a insoluble link between Paradise Lost and Frankenstein that may not necessarily exist or be unanimously accepted.

Is this the voice of Milton’s Satan?

If an encoder wants to delve into this sort of creative encoding, that is, tagging more abstract concepts, that extends beyond simple deletions and revisions and the physical markings of the manuscript, I feel this is an issue they might eventually face, and so would again run into the complication of how “faithful” they were being to the manuscript, by exploring meaning, and marking the text as containing a meaning that is not physically evident in the manuscript.

For me, the process of encoding innately carries with it the sense of what I have been calling “faithfulness”. There is an interesting line to be considered in what defines exactly what an encoder does, what are they allowed to do, and what are their responsibilities in encoding a text that set it apart from editing or annotating a text. These sorts of questions, I think, can help first-time encoders understand exactly what it is they are doing.