Now that Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and a collection of Poe’s stories are available to me, I thought I’d share my second batch of runs on science fiction within the Gothic (if you missed it, here’s the first one).

First: Verne who, together with Wells, comprise the Fathers of Science Fiction. While I don’t think this novel is considered a Gothic work, certainly not in the way The Time Machine is sometimes considered Gothic, Twenty Thousand Leagues nonetheless owes a great debt to this genre. Certainly, the mysterious Captain Nemo resembles classic Gothic characters.

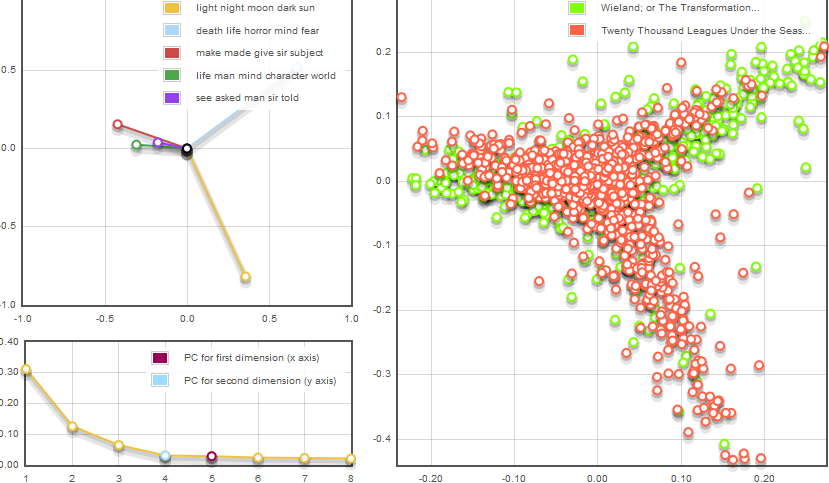

While matching Verne’s novel up with Gothic works, I came across a difficulty that resembled my problem with The Time Machine: a cluttering of novel-specific words. In Twenty Thousand Leagues, the Nautical theme shine through in two categories. Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland, or: The Transformation provided the most interesting results:

Brown’s novel is sometimes categorized as horror, and that shines through here: “death, life, horror, mind, fear.” It’s interesting, however, that Verne’s novel, primarily a science fiction novel arguably emerging from the Gothic, also, to a lesser extent, shares this category.

I decided to investigate this finding by matching up Verne’s novel with other works. This Horror category appeared commonly enough that I was forced to take notice. Is Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea a horror novel after all?

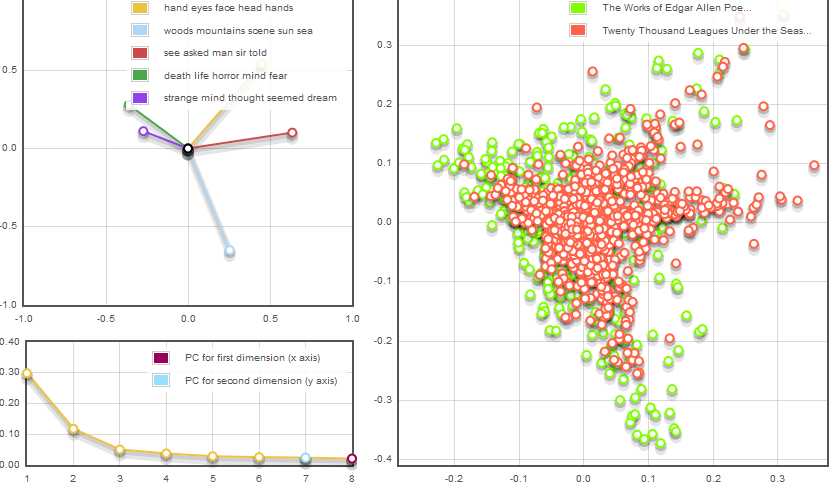

Getting ahead of myself, I matched Verne with Poe, eager to see the results:

First, a note about Poe: the collection included, rather than comprising all of the author’s short stories, totals 23 tales. Moreover, while Verne and Wells can unquestionably be considered science fiction, and to a large extent Shelley, as well, Poe is a mixed bag. He is often credited as popularizing many genres, working within the Gothic to produce mystery, early horror, and yes, science fiction (although, you could argue that the stories themselves can represent several genres at once). With a bit of research, this collection appears to be a healthy mix of these genres. In the future, it might be fruitful to work with a collection only of Poe’s science fiction works.

Back to the results. The Horror topic, as predicted, appears again, with Poe stretching out this subfield further. The other curiosity is: “strange, mind, thought, seemed, dream.” While clearly vague, this category has to do with internal thoughts, a theme that has more to do with Gothic fiction than science fiction. The possibly fantastic element of this category, however, alludes to both genres.

Another note before I move on: while it doesn’t appear here, the semi-“Cosmic” or, more accurately, “Light/Darkness” category, “light,” “night,” “moon,” “dark,” “sun,” frequently occurs in my runs with Verne, presenting an interesting, if tenuous, link to my earlier runs with The Time Machine. Running these two texts alone confirms it, with a fairly strong correlation:

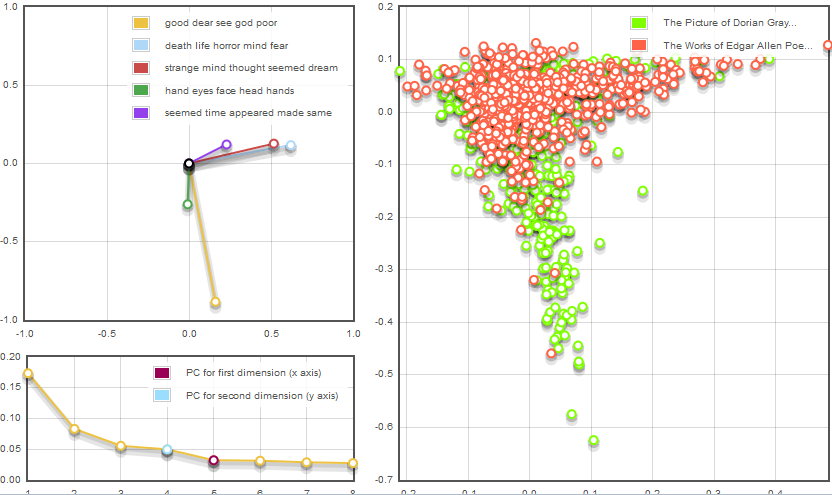

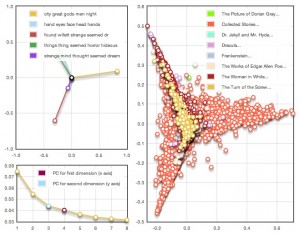

I now centered my attention on Poe, which more easily matched up with the Gothic texts. Running it with Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray produced interesting results:

Once again, you can see Poe’s fascination with Horror. The ambiguous Thoughts/Dreams category appears again, which makes sense because both works contain an element of the fantastic. The word, “seemed,” in this category, as well as in “seemed,” “time,” “appeared,” “made,” “same,” also links it with subjectivity. While this run of course doesn’t point to any clear conclusions, Poe seems to align very well with most Gothic texts, especially ones (like Dorian Gray) that have anything to do with the supernatural and fantastic.

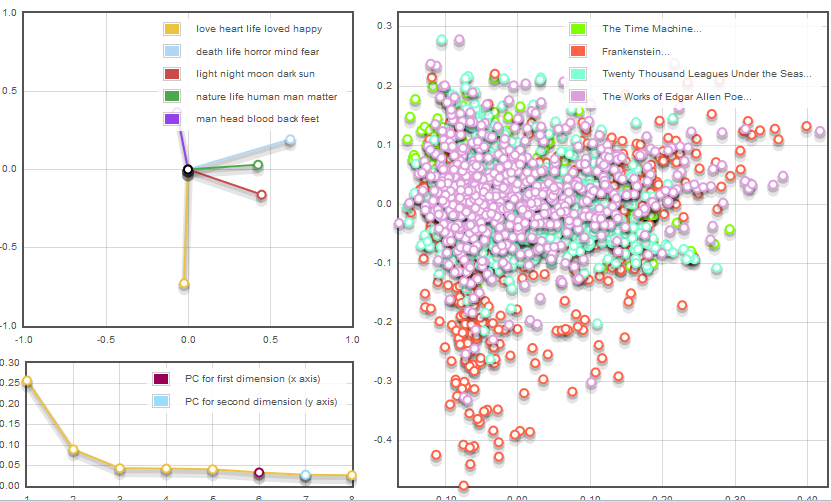

Before concluding, I’ll present the cacophony of running all four science fiction texts together: Shelley, Wells, Verne, and Poe:

My semi-color blindness gave me some trouble here. I don’t want to take these comparisons too far, but there are a few things to mention. First, the appearance of the Light/Time or Sun/Moon category did not go unnoticed. To my mind, none of these texts are primarily concerned with outer space (Poe’s story about traveling to the moon is sadly not included here), but the Sun and Moon probably serve other purposes. Is this focus indicative of science fiction’s fascination with space and the heavens? Possibly, but I don’t think Woodchipper offers any greater insights here.

The reappearance of Horror is curious. Poe, Frankenstein, and Twenty Thousand Leagues spread across this category fairly evenly. What does this mean? Without assuming any familiarity with these works, form this run alone, I would probably sooner group them in the horror genre than science fiction. However, because I know these works together influenced an enormous body of science fiction literature, this run tells me that horror and sci-fi might have more in common than I realize. This makes a lot of sense for Poe and Frankenstein, but Verne surprised me.

An aside about the functions of Woodchipper itself: the ability to zoom in on specific sections of the grid, which I believe was recently added, proved exceedingly helpful for runs with three or four texts like this.

Concerning The Time Machine, Wells’ text expressed the fewest comparisons with the other texts. I used the zoom function and noticed the novel’s nodes scattered among the various categories, but I couldn’t see enough evidence to draw any conclusions here.

As in my first run, I was left with more questions than answers. Science fiction, especially as a subgenre within the Gothic, is especially difficult to locate. Indeed, in this second batch of runs, I encountered more associations with Horror than Science Fiction. This may suggest, however, that the two genres have much in common. This isn’t surprising, considering their roots in the Gothic, and their focus on the fantastic and supernatural. I encountered little that supports the idea that science fiction is concerned more with the societal than with the personal. Indeed, I found the opposite to be true, suggesting that this trend may have appeared later on. Perhaps in using these four authors as a template for future science fiction works, I can trace the origins of later texts in early sci-fi and in the Gothic genre itself. This project may prove useful, but I also suspect that while it has the possibility of producing answers, it’s almost a guarantee that I’ll also be left with more questions, as well.