Here are many of the small notes and ideas that I’ve collected as part of the first few weeks of a creative writing course.

Stories

What is a story?

A story is a conspiracy involving the author and the reader to create something from the text on the page. There is no story until the reader breaths life into the author’s creation. This doesn’t mean that writing can’t be for the author’s benefit. Consider the essay.

The story process is similar to how we translate languages: the writer has a story to tell, so they produce a text which represents the story as they understand it; the reader acquires the text and builds a story which represents the text as they undertand it. A successful author is able to reproduce in the reader’s mind the same story that they started with.

What do stories do?

Successful stories change the reader. If the reader doesn’t feel or think differently after reading the story, then the story might as well not exist. The effect is the same.

Stories are a form of communication. Communication is negotiation. Effective storytelling allows for more effective communication, which results in better negotiation.

Stories should be believable. If they aren’t, they will trigger a mental defense reflex that makes the mind reject what the stories are trying to do. This is called “verisimilitude,” or “being like truth.” If you are a fan of Stephen Colbert, you can consider this the “truthiness” of the story.

Stories can have impossible things happen, but they have to be introduced in a way that the mind will accept them as consistent with the setting. This is a part of the negotiation between the author and the reader.

Even small things can affect the mind’s perception of the story. A successful text (the words on the page, not what the reader imagines) disappears, and the reader is only aware of the story that springs up as they read. Wrong spelling, grammar, or syntax will interrupt this perception of the story because the mind anticipates what should be coming next. When it gets something that isn’t anticipated, it has to stop and reorient itself. This reorientation breaks the flow of the story and makes the reader aware of the text.

Where do stories come from?

Stories come from everywhere: survival strategies, reporting, investigation, learning by playing, entertainment, and escapism. Imagination. Dreams. Synchrony, coincidence, and observation.

How do we develop stories?

We develop stories through mental role play: we talk to ourselves. We also develop stories through writing, stream of consciousness, editing, revision, and reflection.

Plots and Time

Plot is the emotional momentum in the story: how the story progresses in the reader’s time. Time within the story doesn’t have to be linear, but the emotional buildup and release should be fairly straightforward for the reader.

Plots have four ingredients:

- Setup,

- Discovering the problem,

- Discovering the solution,

- Implementing the solution.

The “climax” is the move from discovering to implementing the solution.

Traditional stories have all of the parts. Modern stories tend to leave off the beginning or the end.

Showing and Telling

Characters

Point of View

Story Ingredients

- Plot: emotional momentum

- Character: reader engagement / self identification

- Point of View: reader distance

Choose the mix that fits your story.

Story Archetypes

- Hero’s quest

- Coming of age / transformation

- Stranger in a strange land

- Search / discovery

- Boy meets girl / romance

Main Character

- Succeeds

- Fails

- Abandons the goal

- Goal is undefined

- Audience creates goal

Protagonist vs. Antagonist

Hero vs. Villain

Motivation

Motivation is all about generating momentum. Character and plot motivation are two different things. Plot motivation is insufficient as character motivation.

Beats

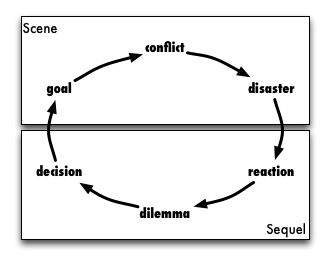

Scene: goal leads to conflict, conflict leads to disaster

Scene: goal leads to conflict, conflict leads to disaster

Sequel: reaction leads to dilemma, dilemma leads to decision

Scenes and Sequels lead into each other.

Motivation is external and objective. Reaction is internal and subjective.

Reactions follow the sequence: feeling, then reflex, and finally rational action or speech.

Motivation involves the senses: what does the character see, hear, smell, or feel (sense of touch)? Feeling (emotions) should follow from the sense. Reflex should follow from the emotion. Action or speech should follow from the reflex.

Any of these can be left out: feeling, reflex, action. If more than one is included, they must be in the proper order for the reader to experience the same thing without being jarred out of the story and made aware of the text.

Proofreading Tips

Resist the urge to explain (RUE)

Read everything out loud at least once. Do the words flow naturally, or do you trip up on them?

Read backwards to catch the wrong word spelled correctly.

Avoid adverbs. They are opportunities to find the right verb.

Pingback: Types of Conflict in Scenes | Writers Write

Pingback: lustra piotrków