Some questions for Frankenstein discussion

Posted by on Thursday, February 9th, 2012 at 9:35 am1. Poor Ernest Frankenstein. Type his name into Wikipedia and you’ll receive an amusing but reasonable redirect:

Ernest gets little page time. He isn’t mentioned in a letter to Victor in which Elisabeth does spend time discussing his other brother (William), and he oddly drops out of Victor’s remembrance instead of becoming more dear as his last remaining family member. (Stuart Curran’s Romantic Circles edition of Frankenstein collects the few references to Ernest here) What is Ernest even doing in the novel? I’d love to compare his place in the different versions of the work–I think it was Curran who suggested that Ernest is written slightly differently in the 1831 edition, and the fact that he remains in the book by that point (with Victor’s forgetting uncorrected) suggests Ernest’s vanishing role is worth exploring.

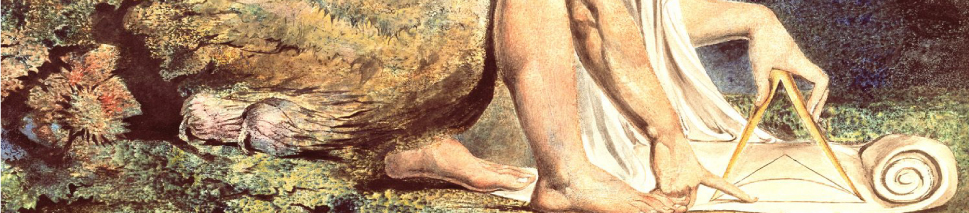

2. What do you make of the strange painting of Victor’s mother posed by her father’s coffin (a particularly creepy subject for Victor’s father to specifically commission)? Does this fit in with Steven Jone’s Freudian reading of Victor’s dream? Or were such subjects par for the course at the time? (Photographs of recently deceased children made to look like they were sleeping weren’t abnormal for the Victorians–though why paint a remembered person as dead/encased in a coffin when you could imagine him as alive within the painting? Did showing his true state conform to some sort of belief about naturalness/reality as reflected by painting?)

I gazed on the picture of my mother, which stood over the mantel-piece. It was an historical subject, painted at my father’s desire, and represented Caroline Beaufort in an agony of despair, kneeling by the coffin of her dead father. Her garb was rustic, and her cheek pale; but there was an air of dignity and beauty, that hardly permitted the sentiment of pity. (Shelley, Frankenstein, unknown page located in Project Gutenberg e-text)

3. In Jones’ Against Technology, he refers to “the story of Frankenstein’s creature who turns into a monster” (my emphasis, 1), an assertion that writes the character as first simply a creature, later monstrous. Is the monster’s monstrosity a result of his manner of birth, his grisly components and visage, or his evil actions? Does he become more or less monstrous during the novel as he gains knowledge, civilization, and other attributes of “humanity”–or does he perhaps simultaneously approach and recede from humanity?

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.

For #3, I would completely agree with Jones – Victor’s fear of his creation is initially expressed in terms of its grotesque exterior (the dull yellow eye, the towering stature), while the creature itself is indeed horrific, yet infantile. Like a human being, he learns to talk, read, and access deeper levels of cognitive thinking (observing the DeLacey’s, which emphasizes his loneliness, and even seeing parallels in his situation to the biblical Adam, in terms of his position of prominence as the first of his kind, as well as in his later insistence for an Eve).

I think the creature’s turning point comes in his torching of the DeLacey cabin – it’s a moment of stark realization for him – despite his basic essence as a human (though some would argue he is more an abomination by way of his birth), he will never be able to fully integrate into humanity – in fact, even brushing against it results in chaos and loss (the sudden departure of the DeLacey’s, the later unpremeditated murder of William). So, in answering Amanda’s question, I believe the creature becomes more monstrous as a result of his gaining of knowledge and “attributes of humanity,” for he realizes that he will forever be an “other” by the very nature of what he is (emphasized by his external unnatural appearance).

However, the “monstrous” actions that the creature commits are not endemic to ‘his kind’ – they are the very things that human beings have been committing for years (and, in some cases, in higher degrees and more sickening methods). Hence, paradoxically, the more “monstrous” the creature becomes, the closer he is to Hogle’s “horrifying double of his creator” idea, as he truly realizes more fully what is inherent within all humans (and this gets back to my Tweet about Golding): man’s inner “beast.”