Introduction

This Site

Historical Context

Initial U.S. Policy for Occupied Japan

Implementation and Revision

The Foreign Other

Definitions

Sources

THE ALLIED OCCUPATION OF JAPAN, 1945-1952: GENDER, CLASS, RACE

The Allied Occupation of Japan (from September 2, 1945, to April 28, 1952), mainly American in personnel and policy, must be seen as primarily a Japanese

experience, but it was also an event of great significance in American transnational history. Upon closer analysis, it looms as also important in the overseas histories of Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Soviet Union. For almost seven years in the aftermath of World War II, Japan, a devastated and defeated nation, was forced to interact at many different levels with large contingents of foreign and armed occupiers of different races, religions, and languages. And when the Occupation finally ended, late April 1952, and the peace and security treaties went into effect, a strong American presence remained in Japan. Beginning in the 1950s, scholars have performed a great service in narrating and analyzing the early postwar history of Japan but have tended to concentrate on political, economic, and security issues rather than grassroots social history or cultural politics. Distance and new global problems have brought fresh perspectives and insights on the meaning and significance of Occupied Japan as a transnational, national, and mutual racial and gender experience. However, the heroes and human faces in existing scholarship on Occupied Japan have been overwhelmingly male. Moreover, the sources in main use, not only in American but also in Japanese studies, have been largely English language official and private documents. With the exception of a handful of well-known Japanese women activists and creative figures—or of prostitutes, who have been duly noted and also much photographed both by foreigners and Japanese—women have been absent from the main narrative of the Occupation and tend to appear in minor roles in reconstructions of life at the grassroots. Japanese housewives, in particular, have been given scant attention and do not even figure as a topic in leading studies of the Occupation, including a recent multiple prize-winning work of history.

Occupation Politics Reconsidered: Oku Mumeo advocating kitchen politics at a railway station in Tokyo, October 1948. This site was constructed with the goal of incorporating Japanese women into the history of the Occupation period, 1945-1952, immediately following Japan's defeat in World War II. It looks at a broad range of activities and draws upon a wide variety of sources. In embracing gender as a vital but neglected means of approach, it also encompasses class and race. Oku Mumeo, whose figure appears on the home page, was a prominent political and social activist from the 1920s to 1945 and won a seat in the Upper House in the first election under the new Constitution of 1947. She also helped to create and lead the Housewives League of 1948 and is sometimes considered to be the founder of Japan's postwar consumer movement. Her name, her achievements, and her philosophy of kitchen politics appear nowhere in early or recent standard histories, although Oku has been rediscovered in women's histories. Yet, even with the advent of women's history in Japan and the rise of feminist consciousness, Japanese women's magazines, newsletters, networks, and creativity in art, drama, and literature, not to mention resilience in daily survival, remain a huge source for study, discourse, and revelation. Another goal in making this site is to encourage research in gender topics and enhance undergraduate studies on Japan across all disciplines from the humanities to the social sciences and sciences.

For general understanding and context, it is important to clarify the policy and attitudes of both victors and vanquished at that stage in their respective histories. It will then be possible through the individuals and themes presented on this site to assess reactions, responses, and initiatives of the Japanese people, in particular women, in the aftermath of defeat and under occupation. It is also important to keep in mind continuities and fissures in modern Japanese history. Although Japan had emerged as a modern industrial society and limited constitutional monarchy by 1900 and created a vibrant modern popular culture in the early 20th century, the Occupiers, unless specially trained, were more apt to think of Japan, their recent and much hated enemy, as totalitarian, with feudal overtones, or at best to view Japanese culture and society as somewhat exotic or not quite within the realm of civilized behavior. In short, Japan was a skewed society in need of American style enlightenment and social reform. Moreover, not to reform Japan would be to jeopardize American global security in the aftermath of World War II and the rise to global power of both the Soviet Union and the United States. The basic chronological framework here is 1945 to 1952, but in order to illustrate patterns and change in Japanese history, it expands on occasion to include a larger span of years from late wartime Japan to the return of sovereignty, 1944-1960.

Conventional power portrait. Note how the artist depicts the relative importance of the three figures: Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, General Douglas Macarthur, and Communist leader Tokuda Kyuichi. Cover of President Magazine, special issue (Tokyo: August 1980). The Occupation began in late August and early September 1945 as a bloodless invasion, but it also occurred in the wake of vast homeland devastation from fire bombs and atomic bombs, ground fighting in Okinawa, the belated entry of the Soviet Union into the war, and the Emperor's recorded radio broadcast announcing surrender. It was in most respects based on American policies formulated in wartime Washington, D.C., although carried out with considerable creativity and magnetism by General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). It was an indirect occupation in that the Japanese government remained largely intact in institutions and personnel from the Emperor and Cabinet to the Privy Council, Parliament, and central and local bureaucracies; the Ministries of War, Navy, Greater East Asia, and the Home Ministry would be disbanded. In addition, Japan was not divided in contrast to defeated Germany and Austria or to liberated but divided North and South Korea, though it lost the prefecture of Okinawa until 1972 and most of the Kurile Islands or Northern Territories to this day. The Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, had reinforced the doctrine of unconditional surrender, promised a military occupation, and indicated several areas of required reform. In more extended and specific terms, the initial U.S. political, economic, and security policy for defeated Japan and the Japanese people was endorsed and made public to the world by President Harry Truman in late September 1945. The document is known technically as SWNCC 150; it had been extensively debated and adopted by the influential State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, which had been created in late 1944 at the Assistant Secretary level.

In summary, the initial U.S. policy called for democratization, demilitarization, and punishment. Subsequent guidelines written by experts on a wide range of important topics were sent to General MacArthur through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The many reforms insisted upon by the occupiers under the rubric of democratization and demilitarization, some modest and some drastic, would range from disbanding the army and service ministries, ending the colonial empire, and mandating civil liberties and a new constitution, to rewriting the civil and criminal codes, legitimating labor unions and collective bargaining, attacking bigness in business, recommending payment of reparations, ending tenancy in village life, and revamping the educational system. Punishment was deemed necessary for war crimes and atrocities committed in the Asia/Pacific War, including the newly defined crimes against peace and humanity as well as the conventional crimes of mistreatment of prisoners of war and civilian internees.

The basic concept or rationale underlying American-style reformism was reeducation of the whole population from children to adults. This entailed winning hearts and minds for peace and democracy by destroying aggressive or militarist mentalities—in a sense, an attempted occupation of souls or psyches—and by thorough reorganization of the formal educational system. Japan was reconstituted as a giant reorientation camp in which there was little direct or formal contact for several years with the outside world. Given that time was short and the objectives extensive, this aim was reinforced by strict Occupation controls over the mass media and telecommunications. Censorship and guidance of the press, screen, stage, and radio, for example, were imposed by the Occupiers during most of the period, September 1945 to November 1949, and for film, still longer, followed by a legacy of self-censorship.

Some of the early reforms, 1945-1948, built on perceived prior trends in Japanese history, but others were largely done by American order, demand, or encouragement. Japanese officials tried, in the words of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, to be good losers, while hoping to undo the worst effects later. American experts on Japan, both scholars and Foreign Service Officers, most of whom knew the Japanese language and had lived in Japan, believed that the Japan they knew in the 1920s was characterized by democratic tendencies. They wished to build upon them, while simultaneously helping to stamp out the repressive laws and institutions of the post 1931 militarists. However, other Americans who became involved in the policy process in 1945, specifically economists with far less or no formal knowledge of Japan, backed a more reformist, even harsh approach to demilitarization and democratization. Both views were reflected in the final policy statement. In so far as possible, the Occupiers sought out sympathetic Japanese to be their front-line collaborators in this great experiment and interacted with their counterparts in the Japanese government. There was virtually no organized resistance against the Occupation; the Japanese populace was unarmed, and the Emperor and high officials were clearly opposed to civil disobedience.

Objections to American policy dominance from Allies who had also fought in the Asia/Pacific War led to the creation of two new international bodies for Occupied Japan: the Far Eastern Commission, which met in Washington, D.C. and held considerable authority, and the less important Allied Council for Japan which functioned as a advisory group in Tokyo for Americans, the British Commonwealth, Nationalist China, and the Soviet Union, the four powers which had signed the Potsdam Declaration, July 1945. By the time both bodies began meeting in March 1946, U.S. policies were well entrenched.

Subsequently, Occupation policies were reviewed by several departments and agencies of the U.S. Government and questioned by Japanese, American, and Allied authorities in Japan. Revised U.S. policies for Occupied Japan, adopted by the National Security Council in late 1948 and endorsed by President Truman, reflected a mixture of official and private concerns: the growing Cold War in Asia, conservative versus New Deal values in the United States, fears that Occupation policies were undermining the Japanese economy, and first-hand experience on the scene in Japan. The revised policy has been misleadingly labeled as reverse course but in reality gave priority to Japan's economy and called for a shift of emphasis in economic policies from punishment to support for revival as a means to ensure a stable democracy. U.S. pressure for agrarian reform, for example, was intensified, while U.S. suspicion of leftist influences in the labor movement converged with those of Japanese officialdom and business. Labor, in return, became disillusioned with U.S. good intentions and was not docile.

With all of this in mind, it is a challenge for students of the Occupation to determine the extent to which the original and revised goals, or the framework and mechanisms for change, in fact deeply affected men, women, and children in Japan both at the time and long after the Occupation had ended. Another problem is to determine the role played by the Japanese themselves, including women, as collaborators and critics of the Occupation or simply as the defeated and dispossessed who went about the business of daily life with little notice of the large foreign presence in Japan. In the midst of chaos and despair, did Japanese, including women, who not actually fought on the battlefield but were patriots at home or complicit in the goals of empire, reflect upon victimization of Japan's enemies or remain mired in their own victimhood?

It is essential to consider the cross section of Americans and Allies who served in Occupied Japan. Did they include women as well as men? What was the thinking among Americans of that time about gender, race, and class? Wartime Washington, D.C., after all, was a heavily segregated city, and mainstream American society was anti-Semitic. General MacArthur's civil affairs advisers in General Headquarters (GHQ), Tokyo, about 3,500 at one point and 2,500 later, were also chiefly American. Again, they were mainly men, as were the Occupation troops. However, several American and Allied women, including women in uniform, played significant roles as resident experts in GHQ, or on local civil affairs teams; they were also nurses; wives or daughters of officers and advisers; clerks and secretaries, or visiting experts, writers, journalists, and entertainers. At the high point in early 1946, the number of American troops in defeated Japan may have reached as many as 200,000, but dropped down to 80,000 before the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. One estimate is that as many as 1,000,000 U.S. servicemen served tours of duty in Occupied Japan from September 1945 to April 1952. By another guess, several hundred foreigners in Japan were American women, and more likely several thousands when including wives and children. The Occupiers, whether male or female, were overwhelmingly white Americans of various European ethnic backgrounds but included African Americans and Japanese Americans. In addition, from 1947 to 1950, the Occupiers also included about 37,000 soldiers from the British Commonwealth of Nations. No Filipino, French, Russian, or Chinese troops were among the official military occupiers, although a handful of civilians of European and Asian background served in GHQ or were attached to foreign liaison offices, such as the daughter of newly independent India's representative to Japan. In such circumstances, social and sexual fraternization emerges as a primary topic in viewing the Occupation not only as an era of social reform but a time of mutual racial and sexual experience.

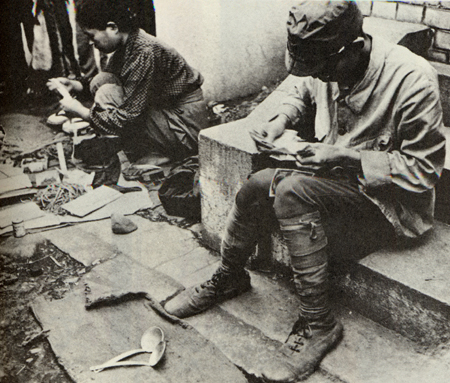

Black market activities in the early aftermath of war, September 1945. Here, a demobilized soldier and a woman, possibly his wife or on her own, sell wares on the street in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo, where hundreds of street stalls sprang up for food, clothes, and daily necessities. In this site, gender refers to "male" and "female" as social constructs as well as biologically determined sex (reflecting ongoing arguments over nurture versus nature). The idealized married woman under Japan's Civil Code, 1898 to 1947, was a good wife/wise mother. Married women had few if any legal rights, and all women were expected to get married. However, the experiences of modern Japanese women were much more diverse in what they did and what they said about gender and sexuality, and the ideal had undergone change before the Occupation. Notions of American womanhood too were much influenced by wartime work, sacrifice, and sexual mores and by the homecoming of millions of men. Furthermore, to give prime focus on this site to women and girls is not to ignore issues of masculinity, especially in the aftermath of total war when millions of demobilized soldiers and returning veterans had to adjust to defeat and occupation, renew relationships with families and friends, and find work. It was not a simple transition from soldier/samurai to salaryman or laborer. Death and devastation on the homefront were experienced by women, men, and children. There were perhaps more wandering and lost boys than girls. The sight of a burned corpse, a girl, a boy, a baby, an adult, transcends gender categories. Mutilated but still living bodies, or bodies irradiated and unable to procreate, suffered loss of gender roles but also endured individual anguish and bitterness. Race refers to the self-conscious attitudes of all parties to skin color and presumed associated traits, attitudes toward intermarriage, and treatment of mixed children as well as to Japanese indigenous and foreign minorities: Ainu, burakumin, and resident Chinese and Koreans. Class is often defined by economic, social, and educational criteria, resulting in such categories as the working and less-educated poor, the affluent or socially prominent elites of the upper class, and, between the two, the aspiring and well-educated middle classes. Where do women fit in? This is the recurring theme in the site.

Since the Occupation required considerable interaction among Americans, Allies, and Japanese, this site draws extensively from Japanese materials in translation as well as official English language records. This includes poems, stories, essays, oral histories, and testimonies. Basic policy documents, such as the Potsdam Declaration, the Emperor's surrender message, initial and revised U.S. policy for Japan, and the new constitution are provided. For students at the University of Maryland, there is the additional bonus nearby of a vast array of primary documents at the National Archives, College Park, and closer at hand, the Gordon W. Prange Collection, chiefly of Japanese materials in McKeldin Library, including books, magazines, and photographs. There are additional original English language materials related to the Occupation in the library's special and microform collections. Visuals too are especially valued here in retelling the story of gender, class, and race in Occupied Japan. The vernacular East Asia Collection, McKeldin Library, contains many Japanese books of photographs, mostly in black and white but some in color, illustrating war and defeat, homefront devastation, and daily life under Occupation. In addition, Archives II has films and stills, much of it untapped by scholars though exploited by documentary filmmakers. Private collections have gradually become available in books, catalogues, or websites and have enriched our understanding of the era. However, most of the photographs were taken by men, both Japanese and Western, and in the case of women often reflect objectification or what theorists call the male gaze. In many cases, photos were censored by Occupation authorities and not seen until years later. Wherever possible, clips from films and songs from recordings will be incorporated in the site.

This exciting primary material must be used with care as to the origin of the document, the point of view expressed, or possibly missing or misleading information. Students should be aware that Occupation censors were careful to ban anything from public discourse which they considered demeaning to the Occupation and the Occupiers or disturbing to public tranquility. For example, many of the photos were not publicly circulated at that time, certainly not those of victims of fire and atomic bombing. Moreover, the Occupation's information officers worked to incorporate materials into Japan's mass media which promoted a favorable image of the United States as well as peace and democracy. As for theory, serious students would do well to become acquainted with the basic arguments of Orientalism, Occidentalism, invention of tradition, the Other, and the imagined community, just a few of the many approaches and devices used by scholars to tease meaning from sources and open up new ways of learning and interpretation.

REFERENCES

The following are for the most part overview histories; also included are three film documentaries which attempt to provide a general review of events and personalities in Occupied Japan. The Gluck essay summarizes historiography on the Occupation period as of 1987. No subsequent interpretive article has replaced it. Students are warned to avoid websites on Occupied Japan; they tend to be inaccurate and misleading.

Booth, John. Occupied Japan: An Experiment in Democracy, documentary film (56 min). Oregon Public Broadcasting and Look East Productions, PBS, 1996

Bowman, Richard (director). The Occupation of Japan, documentary film (30 min). Filmed at the University of Michigan, Japan the Changing Years Series, National Educational Television, 1961.

Dower, John. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Gibney, Alex (producer). Reinventing Japan, documentary film (58 min). No. 5 in Pacific Century series, Jigsaw Productions, 1992.

Gluck, Carol. "Entangling Illusions-Japanese and American Views of the Occupation," in Warren Cohen (ed), New Frontiers in American-East Asian Relations: Essays Presented to Dorothy Borg. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983; 169-236.

Kawai, Kazuo. Japan's American Interlude. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Kurosawa, Akira (director). Stray Dog, Japanese feature film with English subtitles, 122 min, 1949.

Mackie, Vera. Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Mayo, Marlene J. "American Wartime Planning for Occupied Japan." Americans as Proconsuls: United State Military Government in Germany and Japan, 1944-1952. Ed. Robert White. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Press, 1984; 3-51, 447-472.

Mayo, Marlene J. "Occupation Years." Chap. 44, Sources of Japanese Tradition. Ed. William T. Bary, revised edition, Vol. 2, 1600-2000. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005; 323-381.

Molasky, Michael S. The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory. London: Routledge, 1999.

Schaller, Michael. The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Takemae, Eiji. Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy. New York: Continuum, 2002.

Ward, Robert and Sakamoto, Yoshikazu, eds. Democratizing Japan: The Allied Occupation. Honolulu: The University of Hawaii Press, 1987.

|