**A fair warning that this post contains spoilers for the TV show Dollhouse.**

**Also a warning that this is a long post, for which I apologize. I attempted to cover a lot of ground in this essay; frankly, I think there is more I would like to cover.**

One concept we have not yet touched upon in our discussion is that of mimesis. I’d like to use this essay to tease out some questions about mimesis, and explore it as a fundamental concept in Frankenstein, and use it to draw comparisons between Frankenstein, Karel Capek’s R.U.R., and the television show Dollhouse. Common to each of these stories is the intermingling of birth narratives with mimesis. How are these two related? What might each of these, as drawn out in our various texts, tell us about notions of what it means to be human, and the borders between human and not-human?

Promotional Image for the TV show Dollhouse, copyright the Fox Broadcasting Company

Kara Reilly touches on many of these issues in her book Automata and Mimesis on the Stage of Theatre History, including a thorough examination of Hoffman’s “The Sandman” and the 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). Reilly notes in her introduction that “mimesis is among the oldest theoretical terms in theatre and performance theory and is often inadequately translated as ‘imitation’ or representation’; more often than not, mimesis is considered synonymous with realism. However, mimesis has a genealogy that has shifted and changed over time. Part of what is at stake in debates about mimesis is an ongoing tension between art and nature. . .Underneath this conversation about art and nature are anxious questions about the very make-up of reality.” (Reilly, 5)

Gunter Gebauer and Christoph Wulf, in their book Mimesis: Culture, Art, Society, track this shift or change in the meaning mimesis over the course of western history. They approach mimesis from a variety of angles. Mimesis is miming. Mimesis is imitation. Mimesis is emulation. Mimesis is replication. Mimesis is metaphor. Mimesis is rehearsal. Mimesis is becoming like someone. Mimesis is aesthetics. Mimesis is teaching. Mimesis is about making images. Mimesis is about making plot. Works of art are even RECEIVED using mimesis. Mimesis involves, most importantly for modern times, self-referentiality

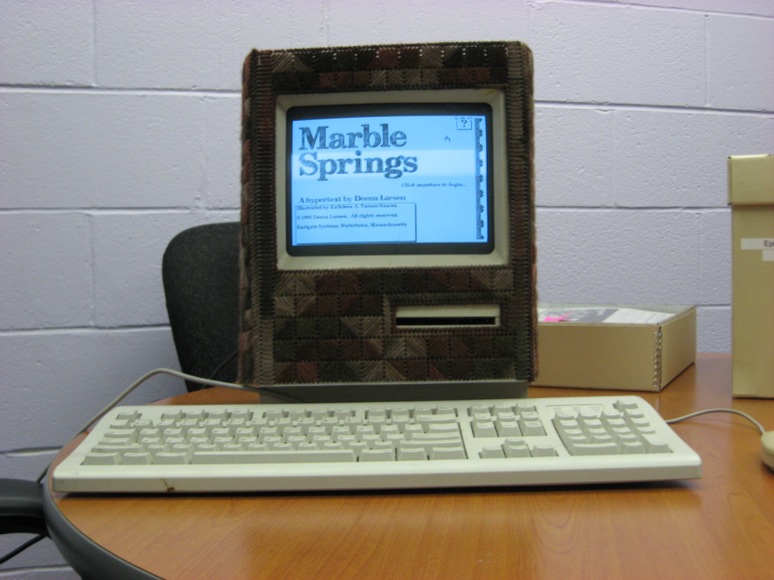

So, if mimesis is imitation, mimicry, emulation, replication, then, the monster in Frankenstein learns via mimesis; he is mimetic. But Frankenstein is also a birth story, with Victor attempting to usurp women’s role in creating human life – how much does mimesis have to do with birth? Does what Victor attempts in creating the monster involve mimesis in relation to the birth narrative? Is he doing mimetically what should never be done mimetically? Also, of course, Shelley’s own writing involves mimesis. And I wonder what could be said about the questions regarding how much of the novel she wrote, as Percy’s handwriting is all over the manuscript, which our class has come to see as we attempt to encode the manuscript into a digital archive using xml (this encoding is also mimesis). How mimesis might help us understand Victor’s actions in the story, for I find him to be a supremely unsympathetic character (unlike the character of Mary Shelley – not the author but the character – in Patchwork Girl).

Of course, our Frankenstein is now just as likely to be mechanically-based, as sewn together from other body parts. One of the first works to imagine that scenario is R.U.R., the Czech play that coined the term “robot” (from the Czech word robota, meaning “servitude” – Reilly also notes that “robotnik is Czech for both worker and serf or peasant.”) (Reilly,148) As Reilly summarizes: “while other early science fiction tales, like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or the Rabbi Loew and the Prague Golem, involve creatures rising up against their creators and harming them, R.U.R. is the first tale that shows the total destruction of human beings by their own technology.” (Reilly,148-9)

Briefly, R.U.R. is set on an island at a factory where Robots are manufactured as a replacement for human workers – with a Robot workforce, humans now have more time for leisure activities. The humans do not see the Robots as having souls, and when a Robot on occasion refuses to work or expresses emotion, it is seen as a product defect. Human birth rates are already plummeting, but the Robots, even as they rise up and kill their human creators, also cannot reproduce (this might also remind some readers of Battlestar Galactica). The two things that separate human beings and Robots at the beginning of R.U.R. are emotional response and the ability to procreate. These two distinctions disappear over the course of the play. More thorough plot summaries can be found online, but this is enough to see that mimesis is integral to the plot of R.U.R., as well as its performance.

WPA Marionette Theater Poster for R.U.R.

And notice too the anxiety over reproduction inherent in the story. The play ends on a hopeful note that the last pair of Robots, who manage to fall in love, will be able, because of that love, to procreate. (Alquist, the last human alive in the play and a builder of the robots, ends the plays by saying “Go, Adam, go Eve. The world is yours.”) (Gassner, 433) All of the Robots in R.U.R. look alike – an obvious bit of Freud’s uncanniness – so will this new race all look like exact copies of each other? Has the phenomena of love between these two Robots somehow changed them into human beings? What is the difference between human and Robot now?

Reilly includes an interesting letter in her chapter on R.U.R., written by an audience member of the New York production and included in the program. The audience member tries to give a nickel to a waitress when a machine (from an automat restaurant) dispenses his muffin but returns the coin. The waitress is so stuck on following protocol at the restaurant, that she will not accept the nickel. The letter writer concludes:

“To myself I said ‘She is one of those Robots that are being manufactured down at the Garrick Theatre in R.U.R. One of those creatures who can only do what they have been trained to do.’ We all come in contact with Robots every day. The human being who has been turned into a machine. They are one of the problems of our time.” (Reilly, 154-5)

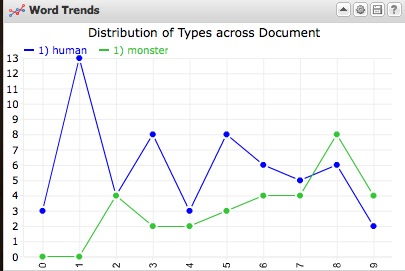

Ultimately, this a shared anxiety in Frankenstein, in “The Sandman,” R.U.R., and in the TV show Dollhouse – what makes humans human, and what separates us from monster or from machine? We have seen one exploration of this in Blade Runner, and there are many others (Battlestar Galactica and Caprica, Terminator, Doctor Who – to name a few that come to mind right away) and procreation is a constant theme in all of them. Specifically, procreation wound up in mimesis.

Dollhouse premiered on the Fox network in January of 2009. Starring Eliza Dushku, the show was created by Joss Whedon, a television and film producer, writer, and director, with a loyal fan base (possibly there are a few in our class). The premise of the show is that there are 20 dollhouses around the world where human beings, known as “actives” or “dolls” are wiped of their identities in order to be imprinted with other temporary identities and sent on a variety of missions. The dollhouses are owned by the Rossum Corporation (a direct reference to one of the shows inspirations – R.U.R.), a powerful global entity with deep ties to governments around the world. The “dolls” have come to Rossum through a variety of means (some by choice, some coerced or forced). The missions can also range from the innocent and altruistic, to the sexual and devious.

When the dolls are in the dollhouse, without an imprint, they walk around calmly saying things like “I try to be my best,” and “friends help each other out.” Over the course of the TV show, we realize that the main character, played by Eliza Dushku, is not necessarily Caroline, Dushku’s political activist who stumbles upon the Dollhouse and is forced to then become one herself, but Echo, originally the imprint-less doll played by Dushku (each dolls name is based on military alphabet – Echo, Whiskey, November, Victor, etc.). The dolls develop personalities and relationships in spite of the science, which becomes important as they realize Rossum has a large plan for this imprinting technology (that, of course, causes the end of the world).

Dollhouse can be looked at through the lens of the Frankenstein story, and there are many moments of parallel imagery. In re-watching a few key episodes one of the most obvious is the chair in the Los Angeles house where the dolls receive their “treatment,” meaning where they are imprinted or de-imprinted with a personality. This is similar to how the novel imagines and the films visualize Victor’s lab, and the use of some sort of machinery or electricity to bring life into the monster. In this case, mimesis is instantaneous, as the human brain (and body) is equated to a computer that can be programmed. But the dolls themselves also become aware to some extent. In the episode, Needs, Adelle, the head of the Los Angeles house, and her staff hatch a plan to allow some of the dolls who are “glitching” to wake up as their original personalities in order to satisfy whatever primal need is causing the “glitch” before shutting them down and restoring them to their imprint-less selves.

The dolls are clearly Frankenstein’s monsters, always cycling through birth and death. Mimesis happens during the imprinting process, mimesis is the imprinting process. And, despite the best efforts of the scientists at Rossum (particularly the genius programmer, Topher, played brilliantly by Fran Kranz – a Frankensteinian name if there ever was one), mimesis “happens” to these dolls or through these dolls. Topher is the most obvious referent to Victor, for he is the one who imprints the dolls (at one point in the series, a distressed Topher asks, “If I think I can figure things out, is that curiosity or arrogance?“), but the show actually takes this idea further. In one of the most well constructed episodes of the first season, The Man on the Street, the main story is intersected with interviews of citizens on the streets of L.A. This episode reveals that the dollhouse is a persistent urban myth in LA – a secret lab under the streets of the city, where people are deprived of their personalities and put to work for those who can afford it. The people react in a wide variety of ways – while some are horrified, many other are tantalized by the idea of being a doll or hiring one, and others think of all the good that could be done so long as the dolls are all human volunteers. Near the end of this episode, an imprinted Echo has her first encounter with Paul Ballard, an FBI agent (played by Battlestar Galactica’s Tahmoh Penikett) who has been searching for Caroline and the dollhouse. She has been sent to beat him up and delay him from returning to his new girlfriend and neighbor (who is at that moment being assaulted by an agent from the dollhouse). But someone inside the dollhouse has corrupted Echo’s programming and she is able to deliver a message to him. She tells him he is going about his search the wrong way. She tells him the dollhouse’s business is pleasure and “that is their business but that is not their purpose.”

The audience glimpses that larger purpose in the unaired season one finale Epitaph One (funny enough, my DVD of that episode opens with a trailer for Wolverine – the creation story for the X-Men favorite). Epitaph One opens in Los Angeles in 2019 (perhaps a nod to Blade Runner?) to a post-apocalyptic scene where the tech that had imprinted the dolls has gone worldwide (via phones, mobile phones, computers, radios, etc. – “ditch the tech” is a common refrain) and brought down the end of civilization. As a character states in an earlier episode, “We’re all just cells in a body.” When another character asks, “Interchangeable?” he answers in the affirmative. As several characters note – the technology exists, there is no going back; it is out there – perhaps now with a mimetic life of its own. Epitaph One follows an unfamiliar team of un-imprinted humans trying to find safety in L.A. They would like to escape L.A., to what is known as Safehaven, where, as one character states, “you die as you are born.” They find a set of tunnels and accidentally stumble on the underground dollhouse, now empty. A familiar face eventually shows up, but we learn it is not Caroline, but Echo/Caroline, now a compilation (a patchwork?) of her imprints and a unique personality (is she human?), who is leading a resistance and can get the team out of L.A.

This is the world of forced mimesis. Birth and death are blurred by the imprint technology. Those who could – the wealthy and the powerful – could eventually take advantage of this technology, not to hire dolls, but to become them. If you can be, not who you are, but who you desire to be, in whatever body you desire to be (originally known in the show as an “upgrade”), the multiple “who” who you desire to be, a series of “who” whose personality never has to die, is that a line between human and not-human? (In 2019 L.A., the resistance team will ‘birth mark’ you – tattoo your name on your back. If you begin to act abnormally, they can ask you who you are and check this against your tattoo.) If we can each birth ourselves, then we have no need for motherhood, or for mimetic phenomenon anymore? Each story we have examined seems to indicate that attempting shortcuts to either leads to the end of what we know as human.

LaRonika Thomas

Works Referenced:

Capek, Karel. R.U.R. Trans. Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair. A Treasury of the Theatre (from Henrik Ibsen to Arthur Miller). Ed. John Gassner. 1950. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954. 411-433. Print.

Gerauer, Gunter, and Christoph Wulf. Mimesis: Culture, Art, Society. Trans. Don Reneau. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. Print.

Reilly, Kara. Automata and Mimesis on the Stage of Theatre History. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print.

Whedon, Joss. Dollhouse. DVD. California: 20th Century Fox Television, 2009-10.