On October 25, 1865, Henrietta Joyce and Elisha Helms stood before a clerk of the court of Davidson County, Tennessee, to confirm Henrietta’s marriage to her late husband, John Joyce. They appeared before the court in Henrietta’s effort to secure a Civil War widow’s pension based on her husband’s military service in the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Like other African American widows seeking a widow’s pension, Henrietta had to produce proof of her marriage to the U.S. Pension Bureau. Elisha Helms was her evidence. Together they swore an oath before the court that Elisha had known Henrietta and John as “living together as husband and wife” for the two years before John enlisted, and later died, in the Union army (Doc. A).1

Twelve years later, on January 19, 1877, Elisha Helms once again stood before a second county clerk to provide testimony in support of the pension application of an acquaintance. This time Elisha was in Maury County, Tennessee, and along with a man named Richard Blanton, testified that a former USCT comrade, Squire Daniels, received a debilitating injury during his time of service in the Union Army (Doc. B and Doc. C).2

By requiring testimony from acquaintances near and far, past and present, pension applications brought people together in tangible ways. Attention to the names that appear on these three documents tucked away in separate pension files held in the National Archives, Washington, D.C., illustrates how the pension application process brought people together literally, by standing together before a county clerk, and figuratively, by drawing on past relationships for the purposes of the present (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustration of the social relationships of Elisha Helms as presented in the pension application files of Squire Daniels and Henrietta Joyce.

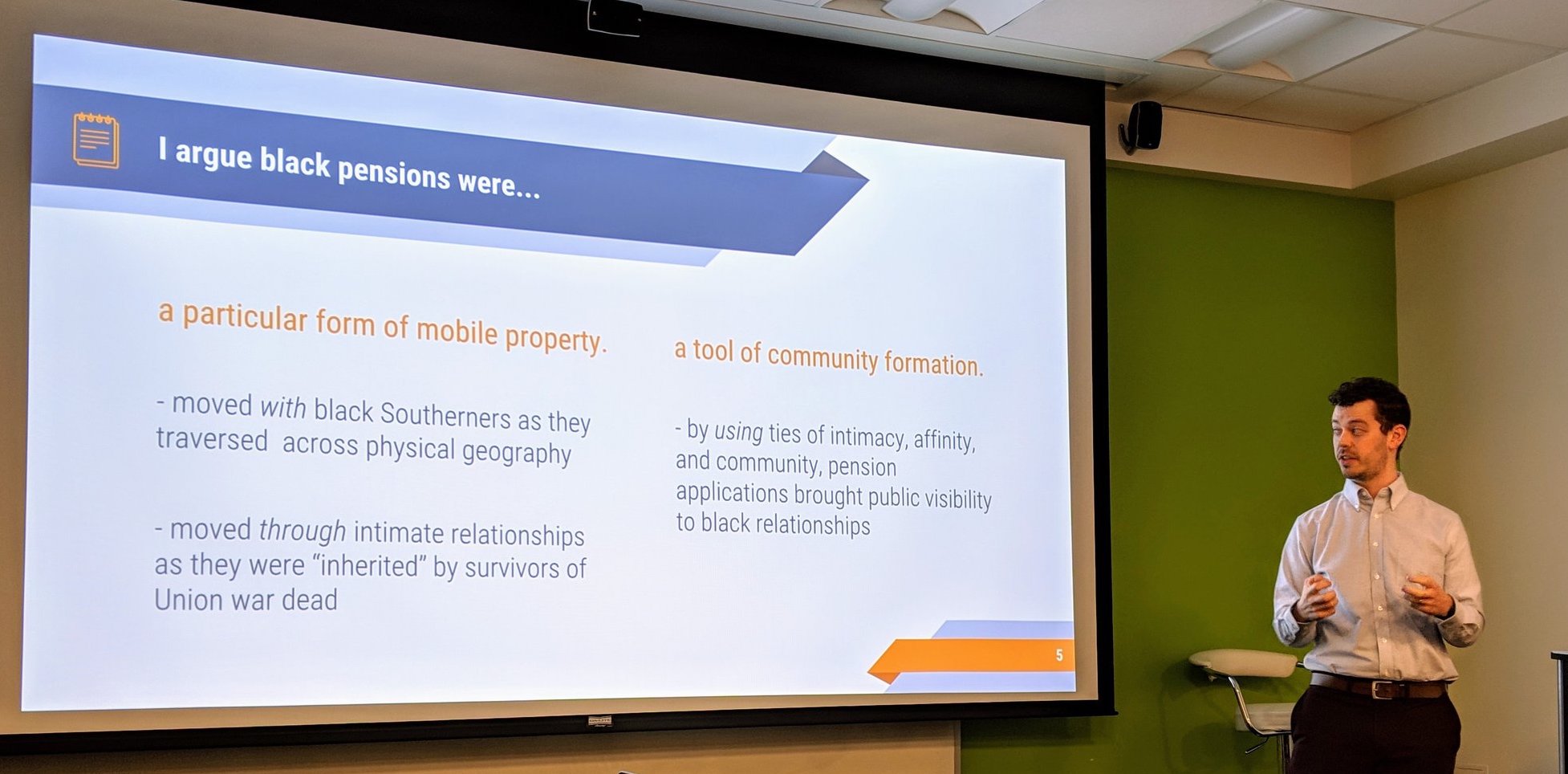

My AADHum project conceptualizes a Civil War pension in two ways: as both a specific form of mobile property and a tool of community formation. Once a pension was secured, it became mobile property, moving with Black Southerners as they traversed the southern landscape. Pensions also moved through intimate relationships as the survivors of the Union war dead applied for pensions based on the military service of their kin. As a tool of community formation, the work inherent in securing a pension drew on ties of intimacy, affinity, and community that brought public visibility to Black relationships in ways that historian—and AADHum Scholar alum—Brandi Brimmer characterizes as indicative of a working-class Black women’s politics.3

Historians have used the Civil War pension applications of Black veterans to explore the life and culture of slaves, the nature of domestic relationships in slavery and freedom, postwar struggles for citizenship, and late nineteenth-century Black working-class politics. Building on this scholarship, I examine how pension applications and the property gained by securing a pension built relationships among Black people and enabled a modicum of economic and geographic mobility for Black Tennesseans in the postbellum South.

My dissertation traces nineteenth-century Black social networks through the data embedded in the legal minutiae of pension applications made based on the service of USCT soldiers. Being an AADHum Scholar has made this project possible by guiding both the theoretical foundation of my methods and developing the digital humanities skills necessary to complete this work.

Conversations and workshops with the AADHum team offered an entry into realms of DH scholarship that wrestle with the practices and ethics of databasing and social network analysis. I was introduced, for instance, to the work of scholars who use a factoid based model (person > document > person) that “links people to the information about them via spots in primary sources that assert that information.”4 Additionally, by introducing me to DH tools such as Tropy (a free software designed for humanities scholars to organize and describe research photos) and Airtable (an online databasing tool that allows linking and sorting between multiple tables and records), they helped get my databasing project off the ground.

The AADHum Intensive also facilitated a valuable discussion with other scholars engaged in Black DH work. Our conversation ranged from the practical—workshopping databasing best-practices—to the theoretical:

- How can we theorize social networks potentially so elastic they stretch both time and place?

- How can we ethically talk about tracing social networks while reckoning with the inadequacy of the archival record to ever record the breadth or richness of social relationships?

- Can Black DH tools (re)create knowledge from sources that run against the purpose for which the sources were originally produced?

Questions like these suggest that this project is, indeed, a work in progress. The Intensive, however, encouraged me to continue research and analysis.

Intensive participants agreed that there was something remarkable in the simple fact that Henrietta Joyce and Elisha Helms stood in the same courtroom together, on the same day, to draw on separate relationships they both had with a man who died over a year earlier. Henrietta, Elisha, and others continued to leverage the relationships John Joyce established in his life long after his death. Perhaps this suggests that to gain a fuller appreciation of Black social networks in the late-nineteenth century we need to call into question the extent past relationships were ever fully past.

1 Declaration of Widow’s Army Pension, 25 October 1865, in claim of Henrietta Joyce, widow of John Joyce (Pvt., Co. A, 23 USCI, Civil War), WC 132930, Civil War and Later Pension Files; Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

2 General Affidavit of Elisha Helms, 19 January 1877, in claim of Squire Daniels (Pvt., Co. A, 23 USCI, Civil War), CC 205957, Civil War and Later Pension Files, RG 15, NARA, Washington, D.C; General Affidavit of Richard Blanton, 19 January 1877, in claim of Squire Daniels (Pvt., Co. A, 23 USCI, Civil War), CC 205957, Civil War and Later Pension Files, RG 15, NARA, Washington, D.C.

3 Brandi Brimmer, “Reimagining the Lives of African American Union Widows in Post–Civil War America,” AADHum Blog.

4 Michele Pasin and John Bradley, “Factoid-based Prosopography and Computer Ontologies: Towards an Integrated Approach,” Literary and Linguistic Computing, vol 30, Issue 1 (April 2015), 86–97.

About the Author

Stan Maxson is a 2019 AADHum Scholar and a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Maryland, College Park.

This is really great work. In my field of social work, social networks are of great importance, especially in indigenous communities or spaces where limited public/govt. resources exist.