The following post has been reprinted with permission from the author, Ravynn K. Stringfield, from Black Girl Does Grad School.

To view in its original form, please click here.

Following the opening session of University of Maryland’s African American History, Culture and Digital Humanities’ (AADHum) “Intentionally Digital, Intentionally Black” conference on Friday [October 19, 2018], the first thing I did was run up for a hug from a young man named Nathan Dize. Nathan and I were strangers in real life; but we were also twitter friends. This process of linking up with people that I knew digitally IRL was a huge personal theme of this particular conference. Not only were we in community by virtue of our research interest, but many of us were connected virtually. While the content of this conference, which I’ll get to I promise, was incredible, a large part of the joy I derived from this experience came from the opportunity to be in physical proximity with the people that provide me with a large amount of my academic support. What does it mean to make the digital physical? Better yet, how does it feel to make the digital physical? For me, it feels like the best of me is being seen, supported and loved. Now, how many academic conferences can you say do that kind of affective labor?

I understand that it seems gauche to talk about love in an academic setting, but so much of my intellectual growth stems from Black women scholars at this conference who loved me simply for being a “Black girl [doing] grad school.” Black women scholars both on twitter and in the digital humanities have nurtured me; they have pushed me; they have included me. While enraptured by wonderful panels featuring Black women scholars, such as Always at Work: Black Women Onlineand Do It For the Culture: Black Humor and Narrative Strategies Online,I found that some of the best intellectual conversations I had with Black women scholars were by chance.

I understand that it seems gauche to talk about love in an academic setting, but so much of my intellectual growth stems from Black women scholars at this conference who loved me simply for being a “Black girl [doing] grad school.” Black women scholars both on twitter and in the digital humanities have nurtured me; they have pushed me; they have included me. While enraptured by wonderful panels featuring Black women scholars, such as Always at Work: Black Women Onlineand Do It For the Culture: Black Humor and Narrative Strategies Online,I found that some of the best intellectual conversations I had with Black women scholars were by chance.

I ran into Dr. Gabrielle Foreman while trying to catch another panel and she talked to me about how she came up with the idea of project CVs, which emphasize collective work for digital humanities projects. Dr. Raven Maragh Lloyd told me about a conversation with her Uber driver on the way to the conference in which she was asked how the work she creates benefits the community. These innovations and questions should lead us to ask our own important questions: who are we serving and why? How can our relationships with community partners be mutually beneficial? How do we adequately represent the work we do on collaborative digital humanities projects? As Dr. Andre Brock and Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson pointed out in their keynote, we also need to be occupied with the banal and the joy that brings— so I point to these examples of everyday joy I experienced while being in an extraordinary, yet admittedly still ephemeral, space.

Though only a temporary space, it was constructed in such a way that everyone could feel included and cared for. From the pronouns on our badges and gender neutral bathrooms at the Riggs Center, to the lactation and quiet rooms, participants were cared for in a way which should be standard. Our humanity was acknowledged, respected and catered to. While I did not take advantage of many of these spaces, it was a comfort to know they were there should I have needed them. These touches (which were by no means “small”) helped effectively translate the communities of safety we have been building online into a physical space.

Though only a temporary space, it was constructed in such a way that everyone could feel included and cared for. From the pronouns on our badges and gender neutral bathrooms at the Riggs Center, to the lactation and quiet rooms, participants were cared for in a way which should be standard. Our humanity was acknowledged, respected and catered to. While I did not take advantage of many of these spaces, it was a comfort to know they were there should I have needed them. These touches (which were by no means “small”) helped effectively translate the communities of safety we have been building online into a physical space.

The lessons I learned while at #AADHum2018 will stay with me throughout my career as a scholar, especially as echoes of the conference will likely reverberate through tweets for months to come. I contended with Timeka N. Tounsel’s idea of “monetized resistance” as I work to reframe the way I think about my own blog for example. (Always at Work: Black Women Online) Tounsel argued that there’s work to be done in reframing the way Black women think about their digital labor— we should not cast it off as leisure, but acknowledge it for the intellectual intervention that it is. Grace Gipson’s presentation, “Exploring the Black Female in Comics Fandom through Digital Storytelling (Black Girl Nerds and Misty Knight’s Uninformed Afro)” gave me a colleague that discusses everything I’m interested in: fandom, aca-fans, Black girl nerds, superheroes, blogs and podcasts all rolled into one. I didn’t know it was possible to make sense of all of those things together, but then again Black women have always found ways to do the impossible. I’m still reeling from Marissa Parham’s incredible talk on the This Code Cracks: A #BlackCodeStudies Roundtable in which she had the audience consider what it would mean for a reader to remix an essay for oneself, amongst a number of other insanely evocative questions, all while dragging sections of her essay, “Break and Dance”, gifs and graphics around a remixable screen. Seeing these powerful Black women scholars captivating audiences with words and technical skill inspired me to walk in my own truth and power. My words are magic too, I just need to learn to harness their energy.

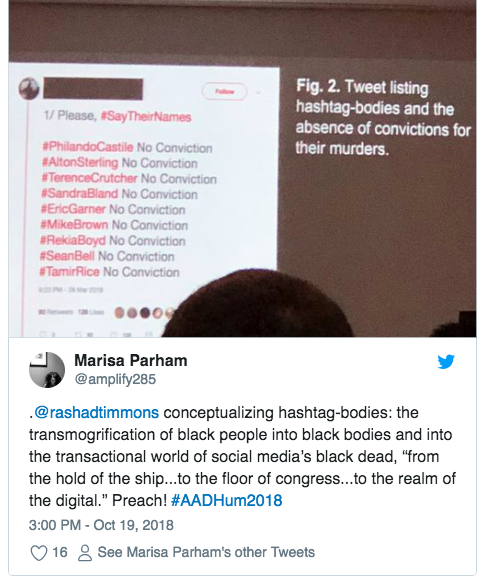

My primary focus on the Black women scholars at this conference throughout this piece stems from a lack of intellectual and emotional sanctuary and support at my own institution. Nevertheless, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the Black men that did not come to play. Dr. Julian Chambliss took time out of his day to talk with me, a budding comics scholar; Rashad Timmons had everybody retweeting quotes from his paper, “Hashtag Bodies, Hegemony and the Deadly Terrain of Civil Society”; and Dr. Andre Brock snatched everybody’s edges with his assertion that colored peoples’ time is a, “Joyous disregard for modernity and labor capitalism.”(He said what he said, y’all.)

My primary focus on the Black women scholars at this conference throughout this piece stems from a lack of intellectual and emotional sanctuary and support at my own institution. Nevertheless, I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the Black men that did not come to play. Dr. Julian Chambliss took time out of his day to talk with me, a budding comics scholar; Rashad Timmons had everybody retweeting quotes from his paper, “Hashtag Bodies, Hegemony and the Deadly Terrain of Civil Society”; and Dr. Andre Brock snatched everybody’s edges with his assertion that colored peoples’ time is a, “Joyous disregard for modernity and labor capitalism.”(He said what he said, y’all.)

In addition to the wonderful roundtables and panels that AADHum put together for participants, there were also digital poster and demo sessions. This was one of the many moments where I wished I could be in multiple places at once during the conference. I wanted to see all of the posters, but I also wanted to experience a demo, as I had never seen humanities people give poster presentations; nor had I seen a digital humanities demo in the way that AADHum had conceived of it. I intended to stop in at each poster for a few minutes, but during the first session I was so enthralled by Sherri William’s presentation, “Amplifying Black Voices Through Digital Journalism,” that before I knew it, a member of the AADHum team was letting participants know that the session was over. The posters provided an excellent alternative presentation format which encouraged both small group and one-on-one conversations around the presenter’s topic; which for someone like me, who is often too intimidated to ask questions in large group settings, was a perfect opportunity to engage with scholarship on a more personal level.

It was beautiful. It was wonderful. It was Black. It was digital. It was an honor to have been in community with so many wonderful thinkers. It was a thrill to watch my digital world transform from pixelated into reality.

It was beautiful. It was wonderful. It was Black. It was digital. It was an honor to have been in community with so many wonderful thinkers. It was a thrill to watch my digital world transform from pixelated into reality.

About the Author

Ravynn K. Stringfield is an American Studies Ph.D. student at William & Mary, specializing in African American Literature and intellectual history, as well as comics studies. She’s also now a budding digital humanist, “in large part thanks to ‘Intentionally Digital, Intentionally Black‘.”

Leave A Comment