It seems that everyone has a different opinion about the “right way” to “do” feminism. The argument about “what constitutes feminism” is being taken up everywhere and by everyone—from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary to Emma Watson. Rather than untangling these arguments here, I propose that these conflicting opinions indicate that we all can and should be more critical and reflective on the ways in which we each enact feminism.

As a rhetorical critic studying social movements, I am grateful that my active participation in AADHum over the past year—first as a community member, and now as an AADHum Scholar—has ushered in a new chapter of my feminist reflection. I have always tried to bring a nuanced, intersectional lens to my work to combat the exclusion and silence of doubly marginalized women. This active desire to bring mindfulness to feminist research is what brought me to the AADHum Initiative in the first place. In this post, I will explain how the AADHum community has helped clarify my concerns about white feminism—specifically the silencing of black women’s agency—and how that perspective is shaping my current AADHum project, “Huddles or Hurdles? Racial and Economic Barriers to Collective Organizing in the Aftermath of the Women’s March.”

As a white-passing Middle Eastern American, I am particularly sensitive to my complicity in a white feminist system that oppresses other women. I often find it challenging to align myself with a movement and ideology that perpetuates so much internal inequity. My study of feminist social movements from a communication perspective also exacerbates my conflicted personal relationship with feminist politics. From a relatively safe position, I bear witness to the exclusionary violence rampant in feminist movements, both today and over the course of history.

AADHum counters such exclusion by centering, recovering, and exploring Black voices and perspectives in a space that is unapologetically Black. Since joining this community in January 2017, I have witnessed scholars refuse to add Black voices as a mere afterthought, or invoke Black voices as self-indulging evidence of their own intersectionality. AADHum’s intellectual projects have also underscored how feminism tends to default to whiteness and, in doing so, colludes with powers of privilege in destructive ways.

For example, during the Fall 2017 Digital Humanities incubators, we analyzed and encoded digitized copies of the University of Maryland’s student newspaper, The Diamondback. In doing so, we grappled with the systematic silencing that Black folks face every day, despite apparent efforts to highlight their experiences. Our conversations and skill-building emphasized how DH tools and methods can recover and amplify voices hushed by institutionalized racism. The incubators compelled me to reflect on the ways that (white) feminism and feminist scholarship similarly and systematically marginalizes Black women’s experiences. More broadly, AADHum programming has encouraged me to engage with Black Digital Humanities work, which is altogether striving to center Blackness and Black voices through digital production and practice.

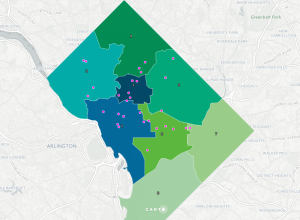

In an attempt to uphold these values in my feminism and feminist scholarship, I have continually revisited a mapping project entitled “Huddles or Hurdles? Racial and Economic Barriers to Collective Gathering in the Aftermath to the Women’s March.” This project was initially designed during a Spring 2017 incubator and was originally interested in studying the Women’s March Huddles campaign and mapping the spatial geography of the campaign’s organizing throughout Washington, D.C. I wanted to make special note of which wards did or did not include a Huddle location, anticipating that both Black and low-income wards might correlate with little or no Huddle organization. Simply, I was originally analyzing black space as a variable that marked exclusion from the localized feminist organizing movement.

In an attempt to uphold these values in my feminism and feminist scholarship, I have continually revisited a mapping project entitled “Huddles or Hurdles? Racial and Economic Barriers to Collective Gathering in the Aftermath to the Women’s March.” This project was initially designed during a Spring 2017 incubator and was originally interested in studying the Women’s March Huddles campaign and mapping the spatial geography of the campaign’s organizing throughout Washington, D.C. I wanted to make special note of which wards did or did not include a Huddle location, anticipating that both Black and low-income wards might correlate with little or no Huddle organization. Simply, I was originally analyzing black space as a variable that marked exclusion from the localized feminist organizing movement.

After inviting feedback from the AADHum community during a Workshop last November, I realized that my project failed to center and amplify Black perspectives. I was reminded that blackness should not be a dependent variable of ward-space and exclusive organizing; rather, Black people and Black space could—and, arguably, should—be at the core of my study. Rather than asking how Huddles’ geographic locations create an ideological narrative of place-based inclusion and exclusion, I am now asking, “how do the Huddles’ geographic location in D.C.’s white spaces signal a larger phenomenon of black mobilization in contemporary women’s movements?”

As I continue to further develop this project as an AADHum Scholar, I am resisting the impulse to use Black space as a symptom of white exclusive organizing. Instead, I am analyzing D.C.’s history of Black organizing to better understand why Black spaces did not take up the call to form Women’s March Huddles. Rather than looking for evidence that the Huddles initiative excluded Black women, I am working to understand their choice to exclude themselves from the Huddles initiative. In other words, I have reoriented my focus to Black women’s agency and their legacy as models of community organizing and social action.

The re-imagination of this project is just one exemplar of the ways in which the AADHum community has prompted me to revisit my feminism—in both research and practice. It is my hope that, by staying an active member of this vibrant intellectual community, I can continue to critically reject mainstream feminism’s overwhelming whiteness.

— Alyson Farzad-Phillips, AADHum Scholar and Ph.D. Student in the Department of Communication, University of Maryland, College Park

Leave A Comment