Throughout the Spring 2017 semester, AADHum has been working to explore, digitize, and make accessible portions of the George Meany Memorial AFL-CIO archives, housed in the University of Maryland’s Special Collections. Guided by a thematic focus on black labor, migration, and artistic expression, Graduate Assistant William Thomas reflects on his experiences, as well as the potential of digitization to enrich and expand conversations at the intersections of African American history, culture, and digital humanities.

Archives, as institutions, are tools that allow the past to inform the present. My interest lies in contextualizing born-digital and digitized records to draw out narratives around how structural racism is constructed and maintained. For every Plessy v. Ferguson or Fugitive Slave Act, every March on Washington and Voting Rights Act, there are thousands of everyday acts of oppression and resistance. Digitization makes it possible to bring more of these stories out of the shadows and connect them to the struggles people are facing today.

This is what excites me about working on AADHum’s digitization efforts with the Civil Rights Division records of the George Meany Memorial Archives. A landmark archive of the history of organized labor in the US, it represents the largest single donation of material to the University of Maryland Libraries, consisting of some 20,000 linear shelf feet of paper and other records. These records literally stretch out for miles.

But what’s in those records? They’re all grouped into sets of boxes, and we have a summary of what’s in each of the boxes. Inside the boxes are folders. What’s contained in a folder in any given box is largely unknown until it is opened and the records examined. When we open a folder we may find records far more exciting than the bland label on the outside.

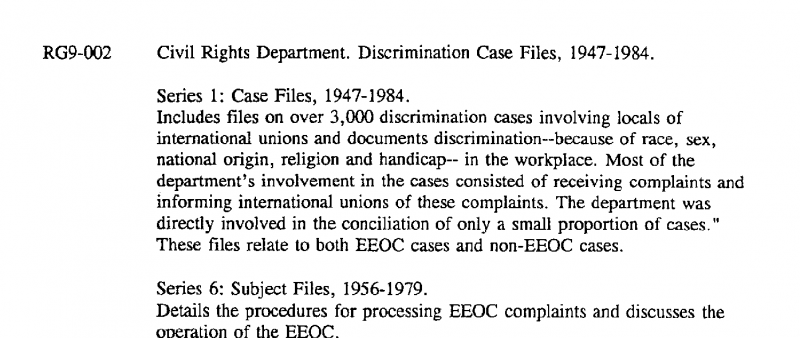

Let’s look at an example of records AADHum is digitizing. The labor law pathfinder tells us that Record Group 9 (RG9) from the Civil Rights Division Subgroup 002 contains some 3,000 discrimination cases.

Box 4 in RG9-002 Series 1 contains a subset of these files.

Each folder in Box 4 is tied to a specific case.

Working our way through the box, we find Folder 19, “Discrimination case files – Clothing and Textile workers, Local 1784, Lawrenceville, VA, 77-17.”

The narratives reflected in the 32 pages of Folder 19 reveal how local labor and civil rights leaders and workers grappled with their small corner of larger injustices afoot in the nation. Its notes, memoranda, and letters about Lawrenceville 1977 make concrete both the intersecting struggles of racism and sexism and the disparate aims of local and national labor and civil rights organizations.

The records show pivotal figures who bridged both movements, such as A. Philip Randolph. They reveal extensive cooperation between the movements. Labor supported Southern campaigns to secure the right to vote, while civil rights organizations supported efforts to overturn section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Section 14(b) was the “right-to-work” section of Taft-Hartley that enabled Jim Crow to extend into manufacturing in the South. They show us the tensions between the movements as well, contextualizing the influences of anti-Communism, Black Capitalism, neoliberalism, and neoconservatism on labor and Black organizations alike: labor forgetting that Black workers matter, while Black leaders attacked labor to bolster their power. They highlight how at times labor solidarity existed at the expense of economic justice for African Americans.

King, AFSCME President Jerry Wurf, and Field Director A. J. Ciampa meeting in 1968 during consultations on the Memphis strike. Copley, Richard L. (1968). “Wurf, King, Ciampa, Memphis,” I Am A Man, https://digital.library.wayne.edu/iamaman/items/show/175.

While not necessarily preserved with this end in mind, we can offer a much richer narrative of African Americans seeking economic justice, post-WWII, by assessing these documents for ourselves and contextualizing them with the benefit of historical hindsight. They also reveal aspects of Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King lives that extend far beyond the frozen icons of Dreaming Man and Grieving Widow.

This deep dive into the RG9 boxes is just the beginning of the digitization process AADHum has undertaken. Anticipating the possibilities digitizing this incredible resource, AADHum’s third incubator used digitized images to construct narratives with the ArcGIS StoryMap tool. StoryMaps offer a vivid way of weaving together images, videos, text, and maps into compelling presentations that both communicate research and allow for novel exploration. Beyond simply framing images with text, storymapping allows us to build narratives using primary materials trace changes over time (e.g., persistent lag of wages in “right-to-work” states vs the national average) and movement in space over time (e.g. expansion of sanitation worker strikes beyond Memphis after April 1968).

Our experiences experimenting with storymaps in our third incubator session are highly encouraging. With this vast collection of material, there are many more stories to tell.

—William Thomas, Doctoral Student and Graduate Assistant to the AADHum Initiative

Leave A Comment