This is the 4th post in MITH’s Digital Stewardship Series. In this post Ed Summers discusses ways to align your content with the grain of the Web so that it can last (a bit) longer.

If I had to guess I would bet you found the document you are reading right now by following a hyperlink. Perhaps it was a link in a Twitter or Facebook status update that a friend shared? Or maybe it was a link from our homepage, or from some other blog? It’s even possible that you clicked on the URL for this page in an email you received. We’re not putting MITH URLs on the sides of buses, on signs, or in magazines (yet), but people have been known to do that that sort of thing. At any rate, we (MITH) are glad you arrived, because not all links on the Web lead somewhere. Some links lead into dead ends, to nowhere–to the HTTP 404. Here is how historian Jill Lepore describes the Web in her piece The Cobweb:

The Web dwells in a never-ending present. It is—elementally—ethereal, ephemeral, unstable, and unreliable. Sometimes when you try to visit a Web page what you see is an error message: Page Not Found. This is known as link rot, and it’s a drag, but it’s better than the alternative.

I like this description, because it hints at something fundamental about the origins of the Web: if we didn’t have a partially broken Web, where content is constantly in flux and sometimes breaking, it’s quite possible we wouldn’t have a Web at all.

Broken By Design

When Tim Berners-Lee created the Web at CERN in 1989 he had the insight to allow anyone to link to anywhere else. This was a significant departure from previous hypertext systems which featured link databases that ensured pages were interlinked properly. Even when the Web only existed on his NEXT workstation Berners-Lee was already thinking of a World Wide Web (WWW) where authors could create links without needing to ask for permission, just like they used words. Berners-Lee understood that in order for the Web to grow he had to cede control of the link database. Here is Berners-Lee writing about these early days of the Web:

For an international hypertext system to be worthwhile, of course, many people would have to post information. The physicist would not find much on quarks, nor the art student on Van Gogh, if many people and organizations did not make their information available in the first place. Not only that, but much information — from phone numbers to current ideas and today’s menu — is constantly changing, and is only as good as it is up-to-date. That meant that anyone (authorized) should be able to read it. There could be no central control. To publish information, it would be put on any server, a computer that shared its resources with other computers, and the person operating it defined who could contribute, modify, and access material on it. (Weaving the Web, p. 38-39).

So in a way the Web is necessarily broken by design–there is no central authority making sure all the links work. The Web’s decentralization is one of the primary factors that allowed it to germinate and grow. I don’t have to ask for permission to create this link to Wikipedia or to anywhere else on the Web. I simply put the URL in my HTML and publish it. Similarly, no one has to ask me for permission to link here. An obvious consequence of this freedom is that if the page I’ve linked to happens to be deleted or moved somewhere else, then my link will break.

Fast forward through 25 years of exponential growth and we have a Web where roughly 5% of the URLs collected using the social bookmarking site Pinboard break per year. URLs shared in social media are estimated to fare even worse with about 11% lost per year. In 2013 a group at Harvard University discovered that 50% of the links in Supreme Court opinions no longer link to the originally cited information. To paraphrase William Gibson, the past isn’t evenly distributed.

There is no magic incantation that will make your Web content permanent. At the moment we rely on the perseverance and care of Web archivists like the Internet Archive, or your own organization’s Web archiving team, to collect what they can. Perhaps efforts like IPFS will succeed in layering new, more resilient protocols over or underneath the Web. But for now you are most likely stuck with the Web we’ve got, and if you’re like MITH, lots of it.

Fortunately, over the last 25 years Web developers and information architects have developed some useful techniques for working with this fundamental brokenness of the Web. I’m not sure if these are best practices as much as they are practical recipes. If you tend a corner of the Web here are some very practical tools available to you you for helping mitigate some of the risks of link rot.

Names

There are only two problems in computer science: cache invalidation, naming things and off-by-one errors. (Phil Karlton by way of Martin Fowler)

Naming things is hard partly because of semantic drift. The things our names seem to refer to have a tendency to shift and change over time. For example if I create a blog at wordpress.example.org and a few years later decide to use a different blogging platform, I’m kind of stuck with a hostname that no longer fits my website. When creating content on the Web it’s important to be attentive to the hostnames you pick for your websites. Unfortunately most of us don’t have time machines to jump in to see what the future is going to look like. But we do have memories of the often tangled paths that lead to the present state of a project. Draw upon these histories when naming your websites. Turn naming into a cooperative and collaborative exercise.

Naming on the Web is ultimately about the Domain Name System (DNS). DNS is a distributed database that maps a hostname like mith.umd.edu to its IP address 174.129.6.250, which is a unique identifier for a computer that is connected to the Internet. Think of DNS as you would your address book, which lets you look up the phone number or mailing address for a person you know using their name. When your friend moves from one place to another, or changes their phone number you update your address book with the latest information. Establishing a DNS name for your website like mith.umd.edu lets you move the actual machine around, say from your campus IT department, to a cloud provider like Amazon Web Services, which changes its IP address, but without changing its name. DNS is there to provide stability to the Web and the underlying Internet.

DNS is distributed in that there are actually many, many address books or zones that are hierarchically arranged in a pyramid like structure, with one root zone at the top. In the case of mith.umd.edu the address book is managed by the University of Maryland. In order to change the hostname mith.umd.edu to point at another IP address I would need to contact an administrator at UMD and request that it be changed. Depending on my trust relationship with this administrator they might or might not fulfill my request. Sometimes you might want to purchase a new domain for your site like namingthingsishard.org from a DNS Registrar. After you paid the registrar an annual fee, you would be able to administer the address book yourself. But with great power comes great responsibility.

Given its role in making Internet names more stable it’s ironic that DNS is often blamed as a leading factor for link rot. It’s true, if you register a new domain and forget to pay your bill, a cybersquatter can snatch it up and hold it hostage. Alternative systems like Handles, Digital Object Identifiers and more recently NameCoin or IPFS have been developed partly out of an inherent distrust of DNS. These systems offer various improvements over DNS, but in some ways recapitulate the very problems that DNS itself was designed to solve. DNS has its warts, but it has been difficult to unseat because of its ubiquitous use on the Internet. Here are a few things you can do when working with DNS to keep your websites available over time:

- Pick a hostname you and your team can collectively live with, at least for a bit. Think of it as a community decision.

- If your new website fits logically in a domain that you already have access to use it instead of registering a new domain name. This way you have no new bills to pay, or management to do.

- If you register a new domain keep your user registration account and contact information up to date. When a bill needs to be paid that’s who the registrar is going to get in touch with. When staff come and go make sure the contact information is changed appropriately.

- Pick a registrar that lets you lock the domain to prevent unwanted updates and transfers.

- If your registrar allows you to enable two-factor authentication do it. You’ll feel safer the next time you log in to make changes.

- If the creator of a website has moved on to other organization, transfer the ownership of the domain to them. They are the ones making sure it stays online so it makes sense for them to own and administer the domain.

Redirects

A more practical solution than minting the perfect and unchanging name for your website is to accept that things change, and to let people know when these changes occur. An established way to announce a name change on the Web is to use the modest HTTP redirect. Think of an HTTP redirect as the forwarding address you give the post office when you move. The post office keeps your change of address on file, and forwards mail on to your new address, for a period of time (typically a year). The medium is different but the mechanics are quite similar, as your browser seamlessly follows a redirect from the old location of a document to its new location.

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) defines the rules for how Web browsers and servers to talk to each other. Web browsers make HTTP requests for Web pages using their URL, and Web servers send HTTP responses to those requests. Each type of response has a unique three digit code assigned to it. I already mentioned the 404 Not Found error above, which is a type of HTTP response that is used when the server cannot locate a resource with the URL that was requested. When the server returns a 200 OK response the browser know everything is fine and that it can display the page. One of the other class of HTTP responses servers can send are redirects, such as 301 Moved Permanently and 302 Found.

301 Moved Permanently is your friend in situations where a given website has moved to another location, as when a domain name is changed, or when the content of a website has been redesigned. Consider the example above when wordpress.example.org no longer works because another blogging platform is now being used. You can set up your webserver so that all requests for wordpress.example.org redirect permanently to blog.example.org.

The actual mechanisms for doing the redirect vary depending on the type of Web server you are running. For example, if you use the Apache Web server you can enable the mod_rewrite module and then put a file named .htaccess containing this in your document root:

RewriteEngine On

RewriteBase /

RewriteCond %{HTTP_HOST} !^wordpress.example.org$ [NC]

RewriteRule ^(.*)$ http://blog.example.org/$1 [L,R=301]

The point of this example isn’t to explain how mod_rewrite or Apache work, but merely to highlight one way (among many) of doing a permanent redirect. Whatever webserver you happen to use is bound to support HTTP redirects in some fashion. When things move from one place to another try to let people know that the website has moved permanently elsewhere. When people visit the old location their browser will seamlessly move on to the new location. Web search engines like Google also will notice the change in location and update their index appropriately, since they don’t want their search results to send people down blind alleys. Consider creating a terms of service for your website where you commit to serving redirects for a period of time, say one year, to give people a chance to update their links.

Proxies

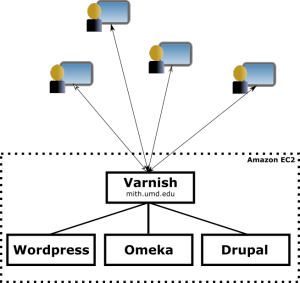

Another pivot point for managing your Web content are reverse proxies. Remember those HTTP requests and responses mentioned earlier? Reverse proxies receive HTTP requests from a client, forward them on to another server and then send the response they receive back to the original client. That’s kind of complicated so here’s an example. Recently at MITH we moved many of our web properties from a single machine running on campus to Amazon Web Services, a.k.a. The Cloud. We had many WordPress, Drupal and Omeka websites running on the single machine and wanted to disaggregate them so they could run on separate Amazon EC2 instances. The reason for doing this was largely to allow them to be maintained independently of each other. We wanted to make this process as painless as possible by avoiding major changes to our URL namespaces. For example the MITH Vintage Computing Omeka site lived at:

http://mith.umd.edu/vintage-computers/

and we didn’t want to have to move it to somewhere like:

http://omeka.mith.umd.edu/vintage-computers/

Certainly the old locations could have been permanently redirected to the new locations for some period of time. But doing that properly for over 100 project websites was a bit daunting. Instead we chose to use a reverse proxy server called Varnish to manage the traffic to and from our new servers. An added benefit to using a reverse proxy like Varnish is that it will cache content where appropriate, which greatly improves user experience when pages have been previously requested. In fact speeding up websites is the primary use case for Varnish. Another advantage to using something like Varnish is that its configuration becomes an active map of your organization’s Web landscape. You can use the configuration as documentation for the web properties you manage. Here’s a partial view of our setup now:

Reverse proxies are an extremely useful tool for managing your Web namespace. They allow you to present a simplified namespace of your websites to your users, while also giving you a powerful mechanism to grow and adapt your backend infrastructure over time.

Cool URIs

When a link breaks it’s not just the hostname or domain name in the URL that can be at fault. What is much more common is for the path or query components of the link URL to change. Unless a URL is for a website’s homepage almost all URLs have a path, which is the part that immediately follows the hostname, for example:

http://mith.umd.edu/vintage-computers/items/show/9

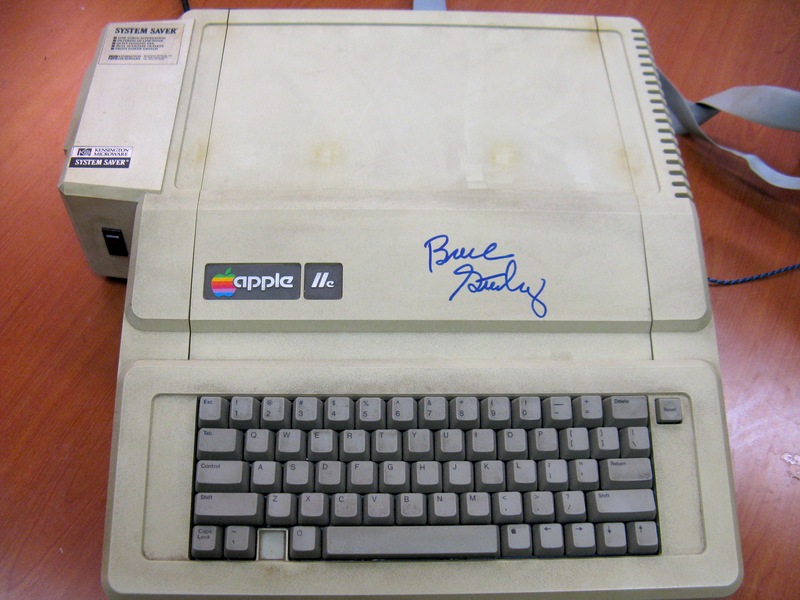

This URL identifies the record in our Vintage Computers website for this Apple IIe computer that has been signed by the author Bruce Sterling:

In addition, a URL may have a query component, which is the portion of the URL that starts with a question mark. Here’s an example of a URL that identifies a search for the word apple in the Vintage Computing website:

http://mith.umd.edu/vintage-computers/items/browse?search=apple

The path and query portions of a URL are much more susceptible to change because they uniquely identify the location of a document on the Web server, or (more often the case) the type of Web application that is running on the server. Consider what might happen if we auction off the Apple IIe (never!) and delete record 9 from our Omeka instance. Omeka will respond with a 404 Not Found response. Or perhaps we upgrade the version of Omeka that uses a new search query such as ?q=apple instead of ?search=apple. In this case the URL will no longer identify the search results.

Even though they are highly sensitive to change there are some rules of thumb you can follow to help insure that your URLs don’t break over time. A useful set of recommendations can be found in a document called Cool URIs Don’t Change written by Tim Berners-Lee himself back in 1998, which recommends you avoid URLs that contain:

- filename extensions: http://example.org/search.php

- application names: http://example.org/omeka/

- access metadata: http://example.org/public/item/1

- status metadata: http://example.org/drafts/item/1

- user metadata: http://example.org/timbl/notes/

Ironically enough the URL for Cool URIs Don’t Change is http://www.w3.org/Provider/Style/URI.html which is counter to the first recommendation since it uses the .html filename extension. Remember, these are not hard and fast rules–they are simply helpful pointers to things that are more susceptible to change in URLs.

In fact you may have already heard of Cool URIs by a more popular name: permalinks. In 2000, Just as blogging was becoming popular, Paul Bausch, Matt Howie and Ev Williams at Blogger needed a way to reference older posts that had cycled off a a blog’s homepage. Necessity was the mother of invention, and so the idea of the permalink was born. A permalink uniquely identifies a blog post which can be used when referencing older content in the archive. The idea is now so ubiquitous it is difficult to recognize as the innovation it was then.

When you create a post on WordPress, or send a tweet on Twitter your piece of content is automatically assigned a new URL that others can use when they want to link to it. The permalink was put to work in 2001 when Wikipedia launched, and every topic got its own URL There are not close to 5 million articles in English Wikipedia now. Previously many websites shrouded their URLs with complex query strings, which exposed the internals of the programs that made the content available, and lent to their transience. Clean URLs inspire people to link to them with some expectation that they will be managed and persistent. Consider these two examples:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permalink

and:

https://twitter.com/jack/status/20

compared with:

http://www.example.com/login.htm?ts=1231231232222&st=223232&page=32&ap=123442&whatever=somewordshere

When you are creating your website it’s a good idea to be conscious of the URLs you are minting on the Web. Do they uniquely identify content in a simple and memorable way? Can you name the types of resources that the URL patterns will identify? Could you conceivably change the Web framework or content management system being used without needing to change all the URLs? Consider creating a short document that details how your organization uses its URL namespaces, and its commitment to maintaining resources over time. You won’t be going out on a limb, because these ideas aren’t particularly new: check out what Dan Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig said over 10 years ago about Designing for the History of the Web in their book Digital History.

Web Archives

In his first post in this series Trevor referred to the distinction between active and inactive records in archival theory, and how it informs MITH’s approach to managing its Web properties. Active records are records taht remain in day to day use by their creators. Inactive records on the other hand are largely kept for historical research purposes. An analogy can be made here to dynamic and static websites. Both types of websites are important, but each has fundamentally different uses, architectural constraints and affordances.

Over the last 15 years MITH has used a variety of Web content management systems (CMS) as part of our projects: Drupal, WordPress, Omeka, MediaWiki, and even some homegrown ones. CMS are very useful during the active development of a project because they make it easy for authenticated users to create and edit of Web content using their Web browser. But at a certain point a project transitions (slowly or quickly) into maintenance mode. All good grant funding must come to an end. Key project participants can move on to new projects and new jobs at other institutions. The urgent need for the project to have a dynamic website can be reduced, over time, to basically nothing. The website’s value is now as a record of past activity and work, rather than the purpose it was initially serving.

When you notice this transition in the life cycle of one of your projects there’s an opportunity to take a snapshot of the website so that the content remains available, and preserve what there is of the server side code and data. The venerable wget command line utility can create a mirror of a website. Here’s an example command you could use to harvest a website at http://example.com/app/

wget --warc-file example

--mirror \

--page-requisites \

--html-extension \

--convert-links \

--wait 1 \

--execute robots=off \

--no-parent \

http://example.com/app/

Once the command completes you will see a directory called example.com that contains static HTML, JavaScript, CSS and image files for the website. You should be able to take the contents of the directory and move it up to your server as a static representation of the website. In addition you will have an example.warc.gz that contains all the HTTP requests and responses that went into building the mirror. The WARC file can be transferred to a web archive viewing application like the Wayback Machine or pywb for replay.

One caveat here is that this snapshot will be missing any server side functionality that was present and not browsable via an HTML hyperlink. So for example a search form will no longer work, because it was dependent on a user entering in a search query into a box, and submitting it to the server for processing. Once you have a static version of your website the server side code for performing the query, and generating the results, will no longer be there. To simplify the user experience you may want to disable any of this functionality prior to crawling. If giving up the server side functionality compromises the functionality of the snapshot it may not be suitable for archiving in this way.

If your institution subscribes to a web archiving service provider such as ArchiveIt you may be able to nominate your website for archiving. Once the site has been archived you can redirect (as mentioned earlier) traffic to the new location provided by your vendor. Additionally you can rely on what is available of your website at Internet Archive. Although you may need to do some work to verify that all the content you need is there. Both approaches will require you to make sure your website’s robots.txt is configured to allow crawling so that the Web archiving bots can access all the relevant pages.

Static Sites

What if it wasn’t necessary to archive websites. What if they were designed to be more resistant to change? In the early days of the Web people composed static HTML documents by hand. It was easy to view source, copy and paste a snippet of HTML, save it in a file, and move it up to a webserver for the world to read. But it didn’t take long before we were creating server side programs to generate Web pages dynamically based on content stored in databases and personalized services like authentication and user preferences. While the dynamic, server side driven Web is still prevalent, over time there has been a slight shift back towards so called static websites for certain use cases.

For example when the New York Times needed to respond to thousands of requests per second for results on election night they used static websites. When healthcare.gov was being launched to educate millions of people about the Affordable Care Healthcare Act in 2013 the only part of the site with 100% uptime was the thousands of pages being managed as a static website. When lots of people come looking for a page it’s important not to need to connect to a database, query it, and generate some HTML using the query results. This is known as the so called thundering herd problem. The less moving parts there are, the faster the page can be sent to the user.

Strangely the same property of simplicity that is useful for performance reasons has positive side effects for preservation as well. The server side code that talks to databases to dynamically build HTML or JSON documents is extremely dependent on environmental conditions such as: operating system, software libraries, programming language, computational and network resources, etc. This code is often custom made, configured for the task at hand and can contain undiscovered bugs that compromise functionality and security. Even when using off the shelf software like WordPress or Drupal it’s important to keep these Web applications up to date, since spammers and crackers scan the Web looking for stale versions to exploit.

Read only static sites largely sidestep these problems since the only software that is being used are a Web browser and a Web server (which is running in its simplest mode, serving up documents). Both are battle tested by millions of people every day. Of course it’s not really practical to hand code an entire website in HTML so now there are now many different static site generators available that build the site once using templates, includes, configuration files and plugins for various things. Once built the website can be made available very easily by copying the files to a Web server which makes them available. StaticGen is a directory of static site generators that lists over 100 projects for 25 different programming language environments.

The next time you are creating a website ask yourself if you absolutely need the site to be dynamic. Can you automatically generate your site using a tool like Jekyll, and layer in dynamic functionality like commenting with Disqus, search with Google Site Search. If these questions are intriguing you may be interested in a relatively new Digital Humanities community group for Minimal Computing.

Export

The last lever I’m going to cover here is data export. If you decide to build your website using a content management system (WordPress, Drupal, Omeka, etc) or a third party provider (Twitter, Facebook, Medium, Tumblr, SquareSpace, etc) be sure to explore what options are available for getting your content out. WordPress for example lets you export your site content as an augmented RSS feed known as WXR. Twitter, Facebook and Medium allow you to download a zip file, which contains a miniature static site of all your contributions that you can open with your browser.

Being able to export your content from one site to the next is extremely important for the long term access to your data. In many ways the central challenge we face in the preservation of Web content, and digital content generally, is the recognition that each system functions as a relay in a chain of systems that make the content accessible. As the aphorism goes: data matures like wine, applications like fish. As you build your website be mindful of how your data is going in, and how it can come out, so it can get into the next system. If there is an export mechanism try it out and see how well it works. If you don’t have a clear story for how your content is going to come out, maybe it’s not a good place to put it.

It may seem obvious, and perhaps old school, but the simplest way for a website to export your data is to make it easily crawlable and presentable on the Web as a network of interlinked HTML documents. If you have a website that was designed with longevity in mind a tool like wget can easily mirror it, and has the added benefit of making it crawlable by search engines like Google or services like the Internet Archive. Stanford University has created a guide for how to make your website archivable.

Use Your Illusion

Hopefully this list of tools and levers for working with broken links on the Web have been helpful. It was not meant to be an exhaustive list of options that are available, but only as another chapter in a continuing conversation of how we can work on and with the Web while being mindful of sustainability and preservation. As Dan Connolly, one of the designers of the Web, once said:

The point of the Web arch[itecture] is that it builds the illusion of a shared information space.

This illusion is maintained through the attention and craft of Web authors and publishers all around the world. Maybe you are one of them. As we put new content on the Web and maintain older websites, we are doing our parts to sustain and deepen this hope for universal access to knowledge. Our knowledge of the past has always been mediated by the collective care of those who care to preserve it, and the Web is no different.

Many thanks to Trevor Muñoz, Kari Kraus and Matt Kirschenbaum for reading drafts of this post and their suggestions.

Hi Ed,

Good article. I’d also mention that decorating links with (among other things) the datetimes can be a simple but really useful way to aid rediscovery and convey temporal intention. See:

http://robustlinks.mementoweb.org/spec/

regards,

Michael