In February 2015, Oklahoma lawmakers attempted to cut funding for new AP history program because it presented a ‘radically revisionist view of American history.’[i] The radically different history that the state government was trying to extricate from the optional AP program was one that failed to highlight a staunch view of American ‘exceptionalism.’ A main concern was that the course had been ‘written in a way that does not promote a particular political position or interpretation of history;’ the subversive history program’s outline wanted to incorporate the United States’ use of WWII internment camps and “moral questions raised by the dropping of the atomic bomb.” The lawmakers’ explicit use of history as a political tool notwithstanding, political censorship of history is, of course, nothing new. But what happens when that history is not quietly censored but openly changed to suit a more desirable origin narrative? When the political system, through its own disquiet, exposes the constructed model of our social and historical beginnings that it desires so desperately to naturalize? Oklahoma did not want the history program to make a more objective or truthful historical account, merely one that viewed the U.S. as the good protagonist. The problem that this event brings to light is not what can be known about our history, but that there is a responsibility of knowing that we have toward our own origin story because we are its architects.

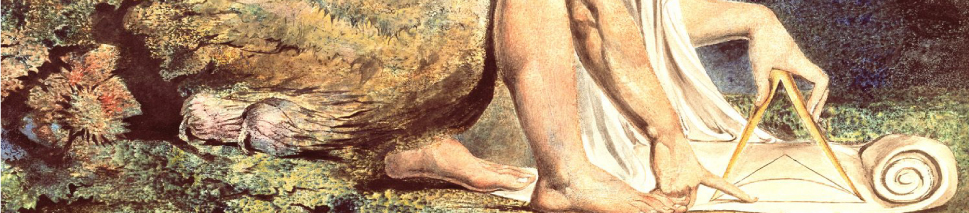

Blake’s The Book of Urizen re-envisions the Western “original” origin myth, taken from the dominant theological perspective of Christianity. What we see when placing this poem in conjunction with our own national narrative is that his 18th century Britain and our 21st century America are not as disparate as they may first seem. Entrenched beliefs about America’s Christian upbringing permeate a large portion of political rhetoric, while we continue to pass laws across the country that push to bridge the gap between church and state. Yet, the point of this essay is not to confront Christianity as a social model, but rather that America’s fervent desire to return to its believed origins warrants a discussion not about particular origin stories, but how origin myths present a unique opportunity to address what we believe to know about ourselves and our responsibility toward that knowledge.

This “responsible knowing” idea relates to recent philosophical work done in both epistemology and ethics, which are directly or indirectly in conversation with a disillusioned attitude toward the possibility of absolute knowledge. Particularly, virtue epistemologists over the last 30 years have been trying to determine the moral implications of knowing when knowledge may be logically indeterminable. Unlike consequentialist or deontological ethics, which focus on the moral implications of “acts” instead of the person, virtue ethics decidedly focuses on the moral “agent” and not the “act.” Similarly, virtue epistemology views knowing/knowledge through the person knowing and not an “objective” knowledge itself. The question that this permits is: if knowing is not about immutable knowledge but about the person/society who does the knowing, then what responsibilities does that person/society have in the act of knowing? Blake’s The Book of Urizen implicitly brings to light the responsibility which emerges when we try to construct a self-identity through a single-perspective, historical narrative. Namely, it calls into question why any particular origin story is at all different from any other, even if their antithetical counterpart ends up in the same eventual place, a state of dictated unity. If knowing our history is not just about the truth of already happened events but an “interpretation of history”, then that history is about knowing ourselves in the present relative to our past.

What Urizen makes us consider in this case is: do we have a responsibility to perpetuate a single-perspective history of America, whereby such an America is always the good protagonist, or does that responsibility extend beyond our own desire for the nation to be its own self-generated savior? If we are a “melting-pot” country, comprised out of numerous cultures, languages, and histories that appear to conflict with the constructed national narrative of “exceptionalism,” are we responsible for incorporating those “other” narratives as well? For good or ill? If we don’t then what nation’s history are we retelling? One that does not and has not existed. That history becomes irreferential with no actual place in time to connect it. If we are responsible, then that forces us to recognize our own fragmented and often self-destructive past, fraught with marring stories of by-gone horrors and subjugative tendencies. Something that, of course, makes us no different from the rest of world; it makes us responsible for being decidedly unexceptional.

[i] Hartmann, Margaret. “Why Oklahoma Lawmakers Voted to Ban AP U.S. History.” Daily Intelligencer: New York, Feb. 18 2015.