Reading our course content thus far really has me stuck on the questions of what, exactly, are language and technology. A particular text that has especially provoked this strain of thinking for me is Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl. One of the dictionary definitions of technology reads, “machinery and equipment developed from the application of scientific knowledge,” and when considering Jackson’s work in terms of this definition, it becomes reasonable to see her hypertext novel as a kind of “machinery,” or, in other words, as a “technology” in itself.

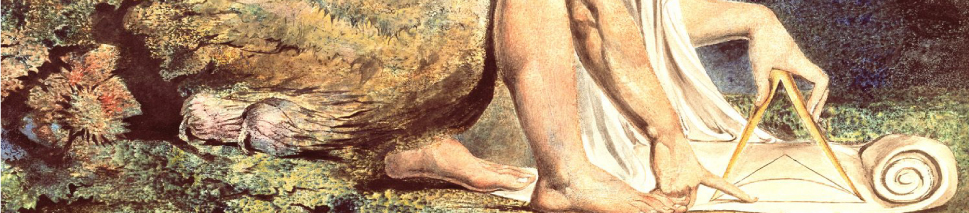

By choosing a digital, hypertext format for her novel, Jackson gives her readers a certain amount of freedom to choose how they access the text. The novel is “rewritten,” (or at least reconfigured each time it is read.) This constant rewriting or reconfiguring of the text is consistent with how Jackson herself patches together Mary Shelley’s original work of Frankenstein with the stories of the female monster (who Victor created for his original monster, but destroyed) and with the stories of the various, deceased women whose body parts are used in PWG to reinvent the female monster.

In her article”Stitch Bitch: the patchwork girl”, Jackson makes a number of compelling statements about hypertext, however one particular point that caught my attention is when she states:

“I noticed in school that I could argue anything. I might find myself delivering conclusions I disagreed with because I had built such an irresistable machine for persuasion. The trick was to allow the reader only one way to read it, and to make the going smooth. To seal the machine, keep out grit. Such a machine can only do two things: convince or break down. Thought is made of leaps, but rhetoric conducts you across the gaps by a cute cobbled path, full of grey phrases like “therefore,” “extrapolating from,” “as we have seen,” giving you something to look at so you don’t look at the nothing on the side of the path.”

Here, Shelley herself seems to suggest that language is a kind of technology by referring to the arguments she herself used to build as “irresistible machine[s] for persuasion.” Her notion that the kind of “machine” built from this kind of reasoning can only convince someone of something or completely fail also tempts us to consider that there is a third option, which she describes as looking at the “nothing.”

Jackson later describes hypertext as “show[ing] the gamble that thought is. She also views it as a medium that welcomes “criticism” and “refusal.” One of the most interesting things she says about writing hypertext, however, is that any author of it must consider the fact that his or her reader may choose to stop reading at any point. She then concludes that “the choice to go do something else might be the best outcome of a text.”

Jackson’s work (specifically PWG) seems to be a call to action to her readers; she constantly invites them to reconfigure and reinvent stories, and she sees writing as a communal, transient act through which stories should constantly be transformed and re-told. If we re-visit the traditional definition of technology as “machinery or equipment developed from the application of scientific knowledge” in conjunction with Jackson’s “Stitch bitch,” is it indeed easy to see PWG, hypertext, and writing itself as a kind of ever-developing technology that is based on a constant application of knowledge. In Jackson’s hypertext, however, this knowledge comes from entering into a constant, written conversation that allows the reader to become the author and vice versa. Like stories, reader/author roles are not permanent within these kinds of texts. They are not only developed, but they are constantly developing.