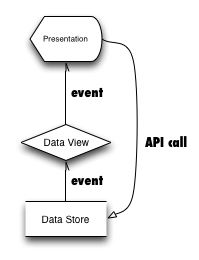

Simplified diagram of information flow in a typical application developed according to the principles outlines in this post.

Underlying all of the scholarly work in a digital humanities project is the digital, something that tends to be swept under the rug along with managing a DH center. I want to spend a little time today talking about how we are approaching the technical side of some of our DH projects, namely how we are designing our JavaScript libraries.

Here at MITH, we want to do more with less. We want our output to be exponential: proportional to how much we have already produced. This means that we have to be able to leverage our past work in our current work. We have to maximize reusability of everything we write.

The problem is that we can’t spend a lot of time on a grant writing code that we aren’t going to use for the grant deliverable. It would be wonderful to be able to create a platform on which we could build our projects, but that platform isn’t a grant deliverable, and probably won’t ever be one because it doesn’t produce anything interesting in the humanities.

To try and get around this problem as we wrote a streaming video annotation client for Open Annotation, we developed a way of dividing up the code that we write so that we have a good chance of reusing it later. Instead of writing a lot more or a lot less code, we end up writing a lot of different code. The lines we draw between different pieces of code are drawn in different places.

The first thing we did was make data central to the application. We created an object that holds all of the application’s information and is responsible for notifying other components if the information changes. We don’t have to worry about copies of the information being out of date. The only component that trusts its copy of the information is the data manager.

Then, we split other pieces up based on responsibility. We have presentations that manage the display of renderings of data items. We have templates that render the items for the presentations. We have controllers that translate user interface events into more meaningful events, allowing us to change the UI interaction without affecting anything else in the application.

Now, we’re working on dividing out a few last pieces that we built for development. We’ll be releasing the application as a library paired with a small demonstration web page showing how to tie the pieces together.

We made at least three fundamental decisions in this process.

First, we decided to build a data-centric application. Everything is designed to reflect the current state of the data. Because of the way we built the data management piece, we can add new kinds of information without affecting anything else in the application. This means that we don’t have to plan just the right hooks for all of the plugins people might want to add to the application. The framework supports them at a level below the semantics of the application.

Second, we decided to divide code into classes based on responsibility, not based on its use of particular data. Types of components are responsible for a few, well-defined things, and those things are the responsibilities of a few, well-defined components. If what we’re trying to write doesn’t fit one of those responsibilities, then it doesn’t go into that component. Components only track what might be called “local” data: information that is specific to the component doing its job and information that is of no concern outside the component.

Last, we went with an event-driven framework for tying the components together. This fits in well with the way browsers work. It also allows our components to be lazy. Instead of each component watching for changing information and figuring out if it needs to take some action, it waits for the data manager to alert it to changes. The responsibility for firing the event lies with the component responsible for managing the information that triggers the event, so this fits well with the other two decisions. Instead of having to change a component if we want the events to come from a different source, which we would have to do if they were coded to watch for particular data changes, we can just reconfigure which listeners are added to which firers.

The resulting information flow is somewhat like that in the diagram: the data store fires its event that something has changed, the date view fires its comparable event if the change is within the scope that it is interested in, and the presentation responds by updating the display of the information. If something happens in the presentation to indicate that something in the data should be changed, the presentation calls a method on the data store to request that the information be changed. This change will lead to another sequence of events.

Before, we would update our presentation of the information in response to an edit. Now, we’re moving to a model where we update our presentation in response to changes in the data, and update the data in response to an edit. This decoupling of input and output ensures that what we see in the presentation will reflect the application’s understanding of the information. If we try to change something and we see it change on the screen, then we know that the application understood what we were trying to do and made the change.

We made a few other decisions along the way that aren’t as fundamental as the above three. We’re moving towards CoffeeScript since it helps us avoid common pitfalls in JavaScript. We’re using that-ism instead of this-ism. We’re working on three levels of documentation: code, API, and tutorial.

By making sure we get the local boundaries of the components right by basing them on a set of principles instead of a project-specific API, we don’t have to worry about fitting into some grand API scheme in order to have interoperability. The end result is a set of components that we can use in other projects. For example, the component that renders the spatial constraints over the video is just as happy rendering them over scans of a manuscript.

We’ll be releasing two libraries in the next few months: the streaming video annotation client and a core library supporting this event-driven, responsibility-oriented, data-centric way of building applications. Both will be under open source licenses.

[…] Source – Designing Applications for Extensibility and Reuse – – Maryland Institute for Technology……, […]