I’ve had the good fortune of being the graduate assistant for the Preserving Virtual Worlds (PVW) project for *mumble* years. The project is a partnership between MITH, The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), Stanford University, and the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). In the first phase (2008-2010) we focused on fairly practical matters: getting videogame data into a form that could be transferred to and stored within a digital repository, packaged with enough descriptive information that a user in the far future might be able to access it meaningfully. You can read the final report here.

In the second phase (PVW2), we’re focusing on what exactly accessing a videogame “meaningfully” entails. What features need to be preserved (and how faithfully) to maintain an authentic experience of gameplay? Within the cultural heritage community, those features essential to authenticity are called significant properties. The InSPECT project says of significant properties:

Significant properties are those aspects of the digital object which must be preserved over time in order for the digital object to remain accessible and meaningful. An institution with curatorial responsibility for digital objects cannot assert or demonstrate the continued authenticity of those objects over time, or across transformation processes, unless it can identify, measure, and declare the specific properties on which that authenticity depends. Nor can it undertake the preservation actions required to maintain access to those objects, unless it can characterize their current technical representations with sufficient detail.

With some items, these properties are fairly self evident. Structure and content are essential to maintaining an authentic copy of an inter-office memo, but aesthetic details like font style and color (with rare exceptions) probably are not. Knowing that we will never perfectly replicate my first experience playing Oregon Trail on a classroom Apple ][, looking at the significant properties raises many questions, few of them with anything approaching a definite answer, most of them with different answers depending who you ask.

- How important is the hardware? Is a game fundamentally changed if it was originally played with a paddle, but is emulated using a joystick?

- If the game was originally intended for a CRT display, is playing on an LCD or Plasma screen authentic?

- How important is sound fidelity? Early games used sound very minimally, because they were limited to the harsh sounds of an internal PC-speaker. (Try playing the “PC beep” sound in your computer’s sound options. Now imagine an entire soundtrack of PC beeps).

- How important is color fidelity? If the blood spatter in a first person shooter was originally PMS 186, do we lose something fundamental if it’s emulated as PMS 185 (Pantone Matching System)?

How do we even begin to answer these questions?! We’re using a three step process:

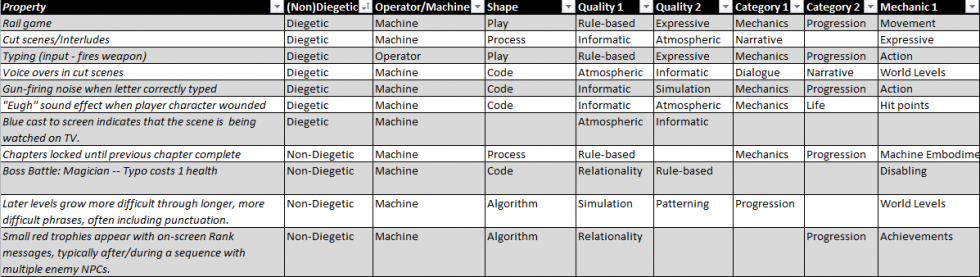

Play through a case set of games and take note of features that jump out during and after play. All project partners did a trial run at this analysis with Typing of the Dead. At MITH, we’ve been tasked to examine titles from the Harpoon, Oregon Trail, and Super Mario Bros. franchises. “Taking note” ranged from spontaneous expressions caught on video as we played, hand-written notes, and post-play captioning of video screen-capture. The notes were then compiled into a list of potential features, which we analyzed both narratively:

“TotD has intratextonic dynamics. While target phrases (the sequences typed to fire at an enemy) follow a pattern, they may change based on the difficulty setting, special items found with the game, or a random algorithm choosing from a set list of options. The first-person perspective is personal. Because the game is on rails with a linear storyline, game action is determinant and predictable, with only limited modification based on difficulty setting, special items, and in-game actions such as rescuing a non-combatant NPC. Standard enemy NPCs move in the same patterns and will have standard phrase lengths and error forgiveness based on difficulty setting and game level. Boss characters are slightly less predictable in that they may be less tolerant of errors, errors might have consequences beyond missing a shot, and battle sequences are longer with some variety to the type and timing of attacks directed at the player. The on rails nature of the game also makes it transient; the player character will continue to move through the game level and be attacked by NPCs regardless of her input into the game. Access is controlled and conditional, with the player required to complete levels linearly, within a certain amount of time/with a certain amount of life points before accessing new content, both playable and not.” (Following the pattern set out by Lars Konzack in his 2002 CDGC conference paper).

And ontologically:

The ontology used above combined Alexander Galloway’s work in “Game Action, Four Moments” (a chapter in a book he edited titled Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture) and an in-house list of mechanics developed based on our own experiences playing games. Later attempts also incorporated the work done by the Game Ontology Project.

Knowing our bias as both players and researchers, the second step has been to interview the actual developers of the games as possible. The developers, however, have their own biases: Both Larry Bond, original creator of Harpoon and Don Rawsitch of Oregon Trail firmly believe that the algorithms and data lying underneath their games are the only features with any significance. While it’s true that in the future a game could be recreated by overlaying a new interface over the back-end data and algorithms, it’s doubtful that many of the original game players would call such a recreation “authentic.”

This is where the third phase of our research will take over. We will be running a series of double-blind experiments in which subjects will play both an original and emulated version of games in our case set, using the original controller. Subjects will be encouraged to verbalize any differences they note and will be given an exit interview to be developed from our experiences and interviews in the initial stages of the project.

Taken together, we hope the data we gather will help us to generate a best practices guide—or at least starting point—for cultural heritage professionals who may be faced with preserving highly interactive digital objects unlike any other digital or physical artifact in their collections.

[…] Cross-posted from the MITH Blog. […]

[…] this link: Videogames as Objects of Cultural Preservation | Maryland … applied-think, digital, humanities, institute, maryland-institute, technology, […]

[…] doctoral student at the University of Maryland iSchool and research assistant at MITH, recently wrote a post outlining the work of PVW2. As Donahue states, PVW2 focuses on “what exactly accessing a […]