Since my last post, I have been working on a grant application. This has afforded the opportunity of some stock taking. I’ve also had some very helpful conversations with scholars in the field: Juan Garcés and Matt Munson in Hebrew Biblical Studies, Tim Finney in New Testament and Desmond Schmidt in textual computing and classics.

1. Collation. Based on very simple normalization and tokenization and a few samples, CollateX will remain error prone, unless the algorithm changes significantly. Examples: (1) In a Mishnah section with repeated words, slight differences in spelling resulted in pushing a whole clause off to the second match. (2) In another passage, CollateX failed to diagnose a missing clause in the text and aligned non matching tokens. My estimate is that currently the error rate is above 10% (for one passage it was about 15%). Better normalization will improve this result. This raises the question of whether the normalization (or, which may amount to the same thing, having CollateX ignore certain characters in comparison) can be carried out automatically, and what this would look like, or whether, as Desmond Schmidt assures me, the whole enterprise is wrongheaded.

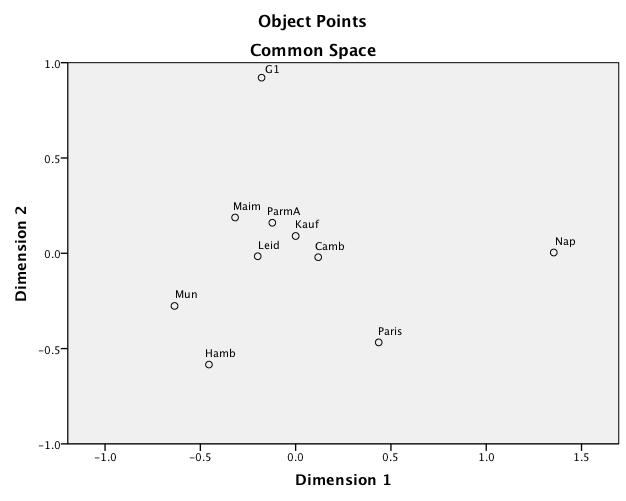

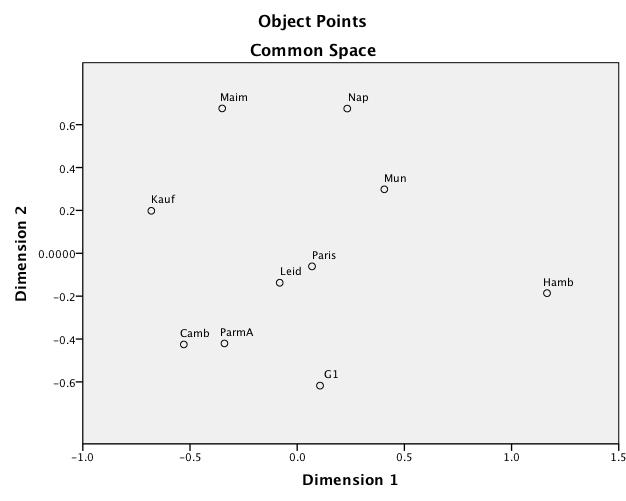

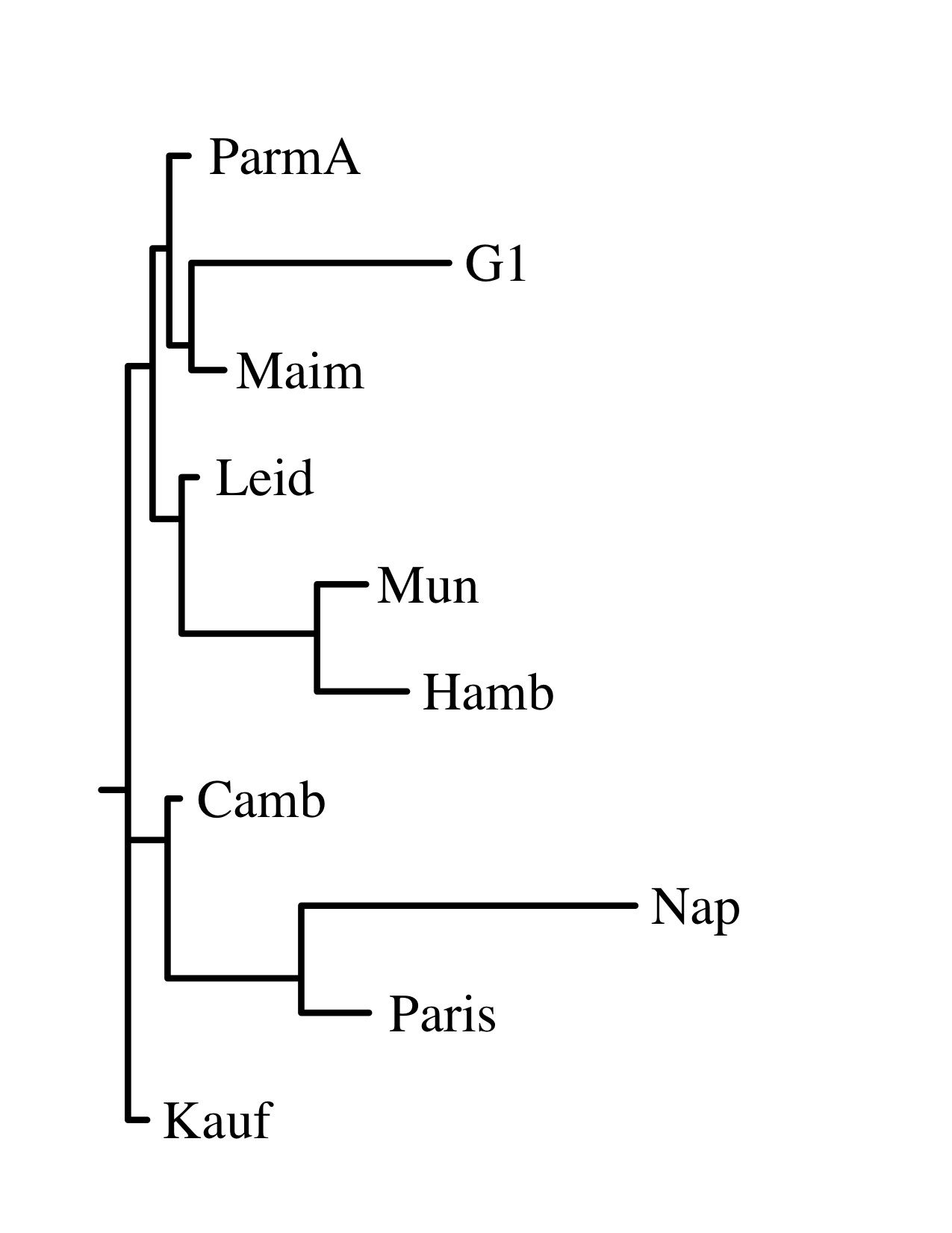

2. Statistical measures, now done by hand, but ideally automated. I have now invested in a license for SPSS. This, and my old friend Excel have allowed me to run some preliminary analyses. First: run collations on every Mishnah section in my sample chapter using a few representative witnesses. Transfer the output to Excel; manually fix the alignment (remember, high error rate). Then start flagging variations. I have opted for a method that is akin to what Schmidt and Tim Finney have used: effectively to create a master document with all possible readings, and use a binary encoding (1, 0) for each witness for whether the reading appears in a given witness. Use SPSS to generate a distance matrix, multi-dimensional scaling (MDS), and clustering. I have also experimented with sites providing a graphic interface to Bioinformatic software (FastME and Phylip) to produce phylogenetic trees.

The results were interesting enough that I wanted to see the results with more careful identification of variance (I’m doing these by hand, after all) and more witnesses. I used the sections with the fullest representation among witnesses (Chapter 2, Mishnah 1-2), choosing a total of 10 witnesses. The results I got were consistent with the larger text sample and fewer witnesses, but neither represented the accepted wisdom on the relationship between manuscripts. I therefore divided the cases between no-variation, substantive (different word, different gender, change in grammatical form), and orthographic (initial waw, matres lectiones, spacing between preposition and word). As an example, the Greek word emporia generated no fewer than six variant spellings, but all represented a recognizable version of the word.

Now, there were some interesting results: the manuscripts thought to be of the “Palestinian type” clustered closely on substantive differences, considerably less so (and differently) on orthographic differences.

Hayim Lapin is Robert H. Smith Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor in the Department of History at the University of Maryland. He currently is completing a faculty fellowship at MITH. This post originally appeared at Digital Mishnah on January 25, 2012.