This post is part 2 in a series about social media data collection experiments conducted in Matt Kirschenbaum‘s Introduction to Digital Studies.

Fred Turner’s interview with Logic Magazine1 was one of the first readings for MITH 610: Critical Topics in Digital Studies, the introductory course to digital humanities at the University of Maryland. Over the course of the semester, we were asked to complete several exercises that incorporated digital methodologies, and I decided to return to Turner’s reading for our mini data story exercise. For this exercise, we were asked to gather a Twitter data set using twarc and to develop a data story with the data we collected.

My central questions were: Is engineering culture “about making the product” as Fred Turner asserts? Is it about more, or less, or something altogether different? These questions motivated me to collect CSV data filled with tweets that included “#engineering.” I am interested in how society constructs the image of engineering and how this image might influence students’ relationships to engineering, including decisions to pursue engineering as a major and interactions with the curriculum once they begin engineering coursework. My working assumption is that we each have an image of “the engineer,” an image that functions much like Alasdair MacIntyre’s “character.” MacIntyre defines character as “a very special type of social role which places a certain kind of moral constraint on the personality of those who inhabit them in a way in which many other social roles do not.”2 If #engineering is what an engineer does, then my concern is how the image of that doing constrains.

While hashtags can be used to follow social justice movements, for example to “reveal a feminist activist assemblage,”3 I want to see if “#engineering” might reveal an assemblage from which I can derive adjectives to describe “the engineer.” Because I am interested in a snapshot of how engineering is depicted, I did not modify the twarc search syntax for “#engineering.” If, as one scholar has suggested, “the concept of the hashtag promises constancy and stability of the image,” then the hashtag offers some insight into the image of engineering4. I wanted a broad range of data from a diversity of users, so I started the search and let it run for several minutes before pausing it. The paused search returned 15,157 tweets sent between Friday, April 20, 2018 and Tuesday, April 24, 2018.

Questions I am interested in answering about this data include:

- Why do people use the hashtag?

- Who uses the hashtag?

- What are the most popular or influential accounts and tweets using the hashtag?

- Who follows accounts that use the hashtag?

- Who RTs tweets with the hashtag and who follows them?

- How do people respond to tweets with the hashtag?

- What types of media, e.g. images and videos, accompany tweets with the hashtag?

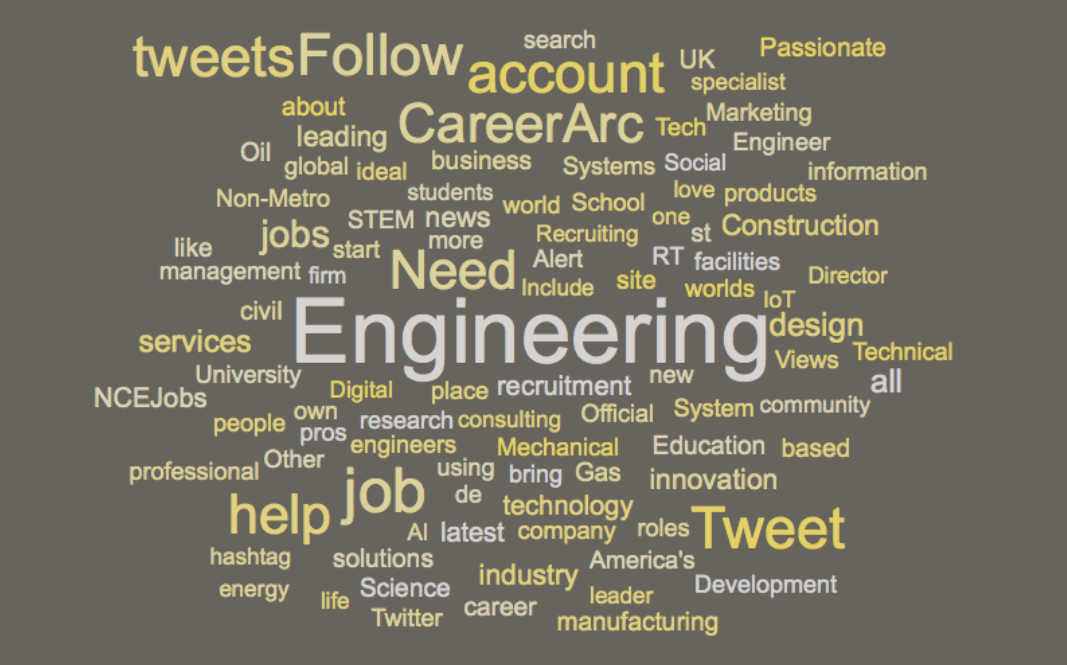

I can posit answers to some of these questions by using spreadsheets and word clouds to analyze the tweets. First, to understand why people might use the hashtag, I generated the word cloud in Fig. 1. It represents other hashtags that accounts used in addition to #engineering within the same tweet. To generate the word cloud, I copied the “hashtags” column from the .csv file into a free online tool, WordClouds.com. The bigger the word appears the more often it occurred.

The words that occurred most often were related to jobs and hiring. Specifically, “CareerArc” is a company that specializes in online recruiting. I was surprised to see jimmyfallon on the word cloud. I discovered that it first appeared in this tweet:

And, then it appears to have been scraped as a hashtag associated with engineering by an account promoting continuing education programs and tweeted over and over again:

To better understand who uses the hashtag, I copied and pasted user descriptions through the same word cloud generator. The results are displayed here:

“Engineering” is the word that occured most often, which suggests that many of the accounts identify with or specialize in engineering somewhat exclusively. The other word that caught my eye was “Need.” Given the high occurrence of career related words, my initial guess was that perhaps users were sharing that they needed a job. However, a small sample of user descriptions with the word “need” suggests that they are framing their expertise as something that is needed. For example:

“For all travelers in India, a Map of India is a must and thus the need for us to find the best map for you.” @MapsofIndia

“Official account of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University – Worldwide. Giving you exactly the education you need, exactly the way you need it.” @ERAUWorldwide

“McFarland Johnson is a recognized leader in infrastructure planning, design & construction management, serving the daily needs of communities throughout the US.” @McFar_Johnson

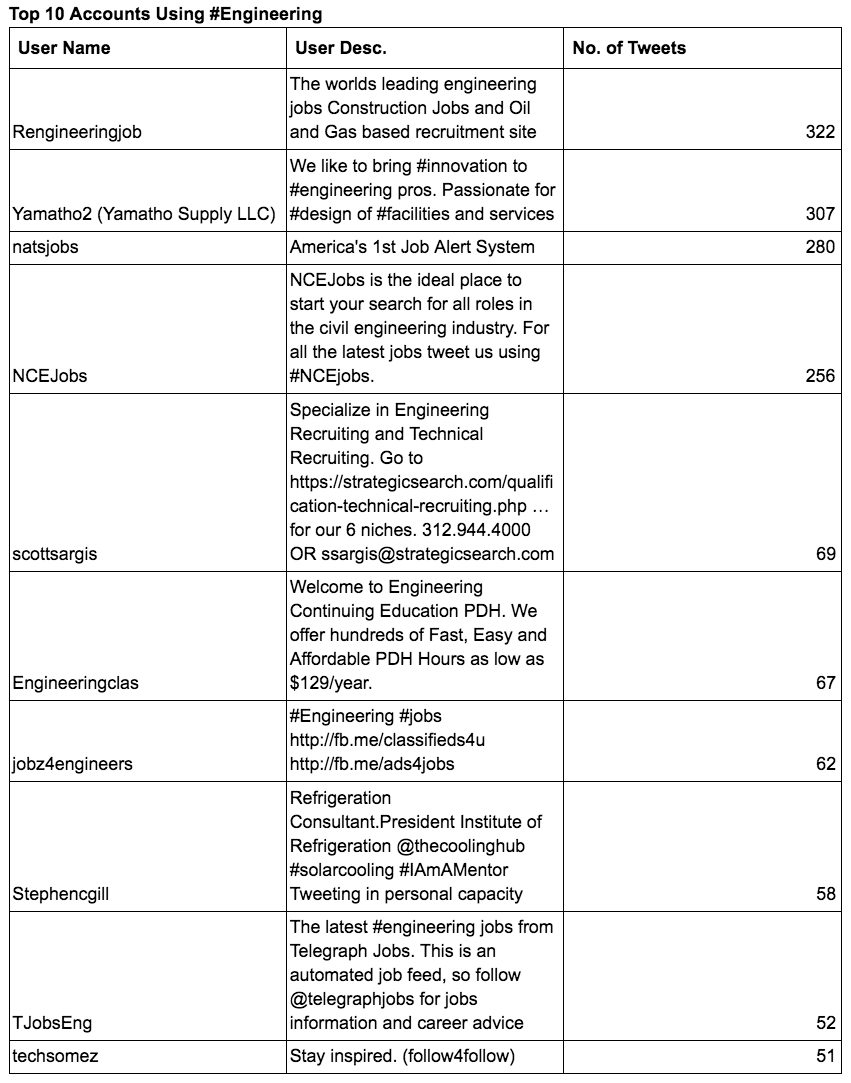

To better understand the “who,” I also used a pivot table to identify the top 10 accounts using #engineering. The results displayed in the table suggest that the hashtag is often used by accounts whose primary function is recruiting.

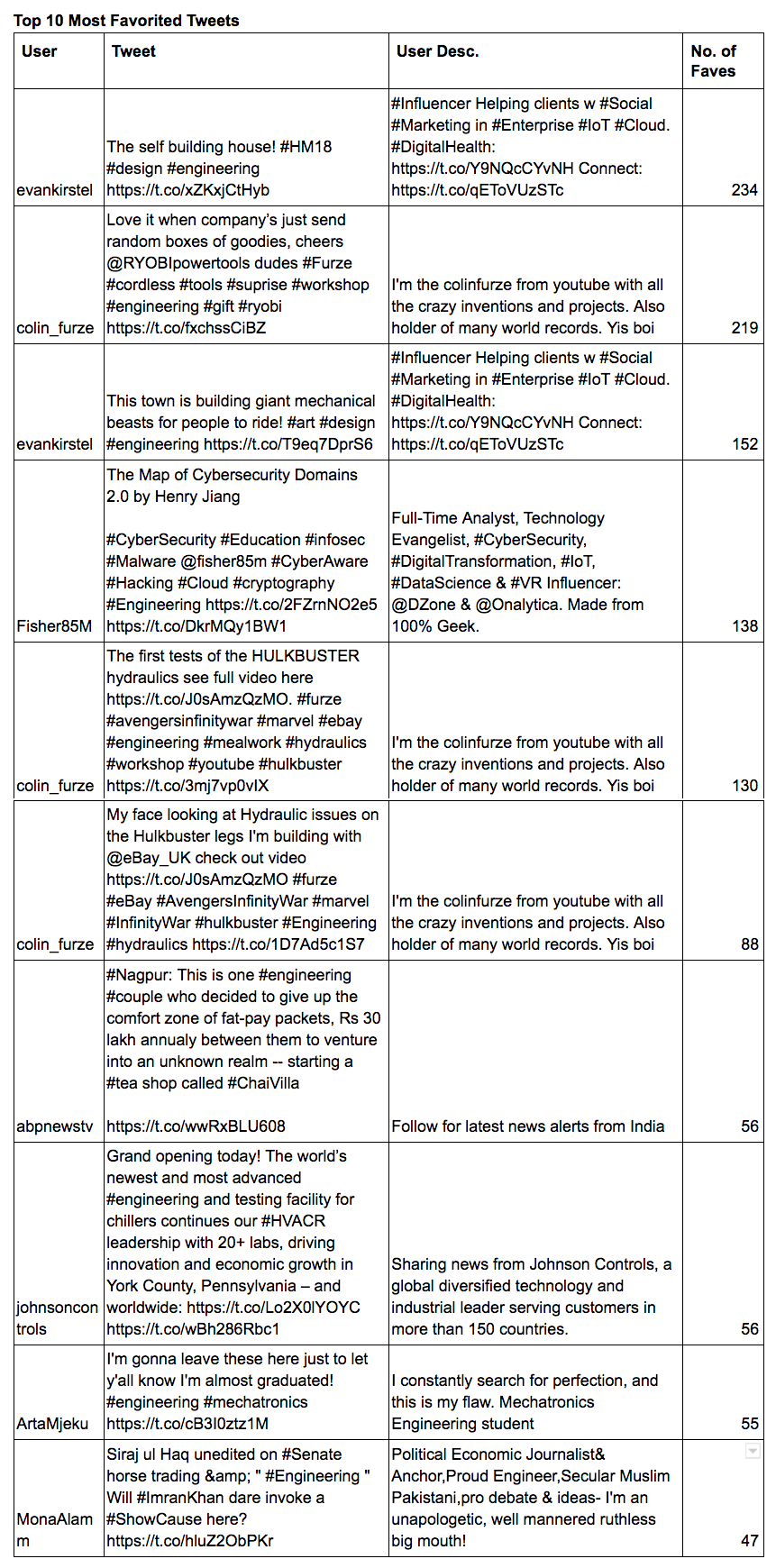

Of course, using the hashtag does not mean that the tweet is influential. To start to identify influential tweets I decided to look at favorited tweets because retweets seemed to be more automated, for example, a circle of accounts all retweeting the same content. Below are the top 10 most favorited tweets. Most of the tweets express wonder at the feats of #engineering. @colin_furze, who also has a YouTube account “with all the crazy inventions and projects,” appears 3 times. He has approximately 35,800 followers. Exploring how the invocation of wonder overlaps with the more pragmatic concern of getting a job could be the focus of future analysis.

I tried to find an easy way to visualize the network/assemblage swirling about #engineering. I do not have previous experience with this, but after a few emails and discovering that NodeXL does not work on on Apple computers, I found GEPHI. I downloaded it and realized it would take a little time to learn the software and properly format my data. Reading about the software, I learned about “nodes” (in the case of Twitter, users) and “edges” (connections between users). Since my own personal discovery, I have seen two scholars present on the work they did with GEPHI, and I realize it is commonly used for visualizing social media networks. To create a clearer picture of the influence of the accounts using the hashtag, mastering GEPHI might be the best next step. However, even with GEPHI, this dataset is limited, and therefore, it may or may not represent what the public assumes about engineering and engineers.

In terms of ethical questions, I realize that the twarc search may have captured private accounts, but the information I have included here seems to be from accounts intended to be public. My goal in collecting this data is to address an ethical question, specifically, “who we see as inventors [or to use my word, engineers], what we see as creativity [or to use my word, engineering], and on whose terms their ideas and practices are valued.”5 Returning to Turner’s opening quote, this mini data story suggests that engineering culture is first about getting a job, not “about making the product.”6 If that is the case, then the use of #engineering is a “digital redline” because it is potentially “creating and normalizing structural and systemic isolation” by constraining who becomes an engineer7. This constraint could function both materially (perhaps only certain people can see the job posts) and symbolically (perhaps the image of who is an engineer prohibits some people from pursuing those jobs). Equally important is how the explicit connection between engineering and economic opportunity may also constrain the actions of engineers. Remembering MacIntyre’s definition of character as placing “a certain kind of moral constraint on the personality of those who inhabit them,” the key questions to pursue include who can become the character who engineers and, what can the character of the engineer engineer when the prominent value is getting and keeping a job.8

References

1 Fred Turner, “Don’t Be Evil: Fred Turner on Utopias, Frontiers, and Brogrammers,” Logic Magazine, https://logicmag.io/03-dont-be-evil/.

2 Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 27.

3 Carrie A. Rentschler, “Bystander Intervention, Feminist Hashtag Activism, and the Anti-Carceral Politics of Care,” Feminist Media Studies 17, no. 4 (2017): 568.

4 Tara McLennan, “Hashtag “Sunset,”” The International Journal of the Image 7, no. 1 (2016): 33, doi://10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v07i01/33-43.

5 Shirin Vossoughi, Paula K Hooper, and Meg Escudé, “Making through the Lens of Culture and Power: Toward Transformative Visions for Educational Equity,” Harvard Educational Review 86, no. 2 (2016): 207.

6 Turner, “Don’t Be Evil.”

7 Safiya Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: NYU Press, 2018), Loc. 286, Kindle.

8 MacIntyre, After Virtue, 27.