Arte Público Press, Recovery Project, Social Justice and DH Speaker Series

Feb 15, 2018 · Houston, TX

I want to frame my talk around a quote from Community Futures Lab co-director Rasheedah Phillips from her workshop “Time, Memory, and Justice in Marginalized Communities.” She states “Oral Futures is about speaking into existence what you want to have happen.”

I want to think with you today about how such future-making materials are collected, preserved, and made accessible in a moment of extreme climate change and the attending displacements of people and animals due to environmental and political-economic erosion of homelands and sites of cultural heritage.

We cannot save everything, nor would we want to. Decisions have to be made about what to keep and what to discard; these decisions encode and reflect particular values, privilege and power structures—some decisions about what to be kept go against the community’s desire for privacy or restricted access to materials; this is a tension between surveillance and privacy, between visibility and erasure. Yvonne Perkins writes, “In the past people such as women, non-Europeans, Aborigines, the poor etc were not considered important contributors to our history so their stories are often not portrayed in archival records, or they were obscured in the archives by the social conventions of the time.”

Archives—in this usage I mean institutional, community, as well as digital collections curated by scholars—do not only exist to explain or contextualize the past, but also signal towards and shape futures. Archives call to the fore the processes of preservation, memory, and access. As Brit Stolli notes, attending to these processes raises uncomfortable questions of who decides what is significant to carry forward, in whose memory is the past best preserved, how do we (and who exactly counts as ‘we’) determine the ethical framework through which to focus our efforts of preservation and future-shaping? Absences and obfuscations are referred to as archival silences. Michel-Rolph Trouillot outlines the ways voices from the past are silenced:

- there is a silencing in the making of sources. Which events even get described or remembered in a manner which allows them to transcend the present in which they occurred? Not everything gets remembered or recorded. Some parts of reality get silenced.

- there is a silencing in the creation of archives—in this usage, Trouillot means repositories of historical records. At times this archival silencing is permanent since the records do not get preserved; other times the silencing is in the process of competition for the attention of the narrators, the later tellers of the historical tales.

- And thirdly, the narrators themselves necessarily silence much. In most of history the archives are massive. Choices, selections, valuing must be done. In this process, huge areas of archival remains are silenced.

These silences occur along a spectrum of accidental to intentional, from the creation of records, to the identification of such records as valuable (value set within formal, institutional repositories reflect the needs of the state and those who hold structural power), to the resources to preserve and carry forward records, and to the ways in which records are described, catalogued, and organized.

Further, silencing can occur as sites of sources and records are suppressed, lost, damaged or destroyed through climate change.

I have been backing into a definition of archives, the Society for American Archivists defines archives as:

- Materials created or received by a person, family, or organization, public or private, in the conduct of their affairs and preserved because of the enduring value contained in the information they contain or as evidence of the functions and responsibilities of their creator, especially those materials maintained using the principles of provenance, original order, and collective control; permanent records.

- The professional discipline of administering such collections and organizations.

- The building (or portion thereof) housing archival collections.

What this definition obscures are the variety of non-institutional, community archives and collections of digital sources curated by scholars for a particular research question or goal (many projects in the digital humanities). Further, the SAA definition understates the extremely nuanced and value-ladened decisions that drive how archives identify materials and process those materials for public use. From an archivist view, archives are repositories which collect unique and rare materials from outside sources through donation or purchase based on specific collecting goals, and makes these materials accessible via a series of practices that range from organization/arrangement, naming, and describing materials, as well as decisions regarding access and privacy—with documentation of these decisions often not easily accessible by researchers/users of archival collections. It sidesteps the construction of pasts and futures as well as the processes in which those pasts and futures are navigated and imagined through a seemingly neutral stance.

As Mario Ramirez writes, “continued assertions of neutrality and objectivity, and a rejection of the ‘political,’ take for granted an archival subject that is not only homogeneous (free of racial stereotypes, societal influence, prejudice, and political opinions), but that also supports whiteness and white privilege in the profession and within archival holdings.” I lean on Michelle Caswell’s observation that what is constructed as ‘neutral’ is a matter of perspective, and such perspectives remain limited given the homogeneity of the archival field.

There is an inherent violence in archival work–silencing and obscuring of people and sources, creating and sustaining hierarchies through collection practices that value some voices and experiences over others, through naming practices, controlled vocabularies, and description, as well as hiding/devaluing the labor involved in this work. Terry Cook emphasizes from the ancient world to the present women (and people of color, LGBT communities, and other non-white, heteronormative, able-bodied people) have been de-legitimized in archival processes.

How can we deconstruct this silencing and archival violence, to build an anti-violent, anti-racist, woman-ist practice instead? Within this reflective, critical archival work, how do concerns of climate change put pressure on—and reshape—this striving for practice?

The term Anthropocene signals the current moment of mass extinctions and climate change resulting from human activities. But as Donna Haraway suggests it is both too big and too small. It posits a ‘universal’, in her words ‘as if it’s humanity or man that did this thing (meaning environmental damage), without connecting this damage to the processes of building wealth through extermination and extraction of animals, peoples, and natural resources. Haraway suggests the term capitalocene to better situate human activities within the robust networks of animals and plants, and within timescales of near and distant pasts and futures.

For this talk, I am using the more familiar Anthropocene, while drawing on the messier networks and timescales of capitalocene, holding on to the troubling notion of a ‘universalism.’ My usage intends to focus on the social, political, and economic pressures that are connected or result from the process of extermination and extraction of resources. These processes displace millions of people, leading to an even greater pressure on the records and sites of memory and heritage.

As scholars, digital practitioners, and librarians and archivists, striving for a more just practice for collecting, describing, and stewarding the sources of cultural memory, I lean on David Wallace’s outline of a social justice approach to archives, which “embrac[es] ambiguity over clarity; accept[s] that social memory is always contestable and reconfigurable; understand[s] that politics and political power is always present in shaping social memory; consider[s] that archives and archival praxis always exist within contexts of power; … recognize[s] the paradox of archives and archivists as loci of both weak social power and significant social memory shaping potential; and acknowledge[s] that social justice itself is ambiguous and contingent on dissimilar space, time and cultural contexts.”

With this in mind, I am going to pivot to a reflection on an approach to digital work that Jeremy Boggs, of the Scholar’s Lab at University of Virginia, and I have called Advocacy by Design.

In 2014, the disappearance and murder of University of Virginia undergraduate Hannah Graham, the Rolling Stone ‘After a Rape’ article, and the assault of African American student leader, Martese Johnson, by two Alcoholic Beverage Control agents led to the development of Advocacy by Design. The cries of ‘how could this happen here?’ and ‘we had no idea!’ were discordant with the long history of sexual and racial violence at UVa.

Together with Professor Lisa Goff, the Scholars’ Lab team organized a digital archive to document this history at the university. Jeremy and I felt the archive must be feminist at the core, that feminist principles must be present at each stage-from collecting materials, to describing and organizing metadata, to the interface, to the ways in which the archive was shared. While we continued to work on Take Back the Archive, we felt this feminist mode of working could be extend to other projects.

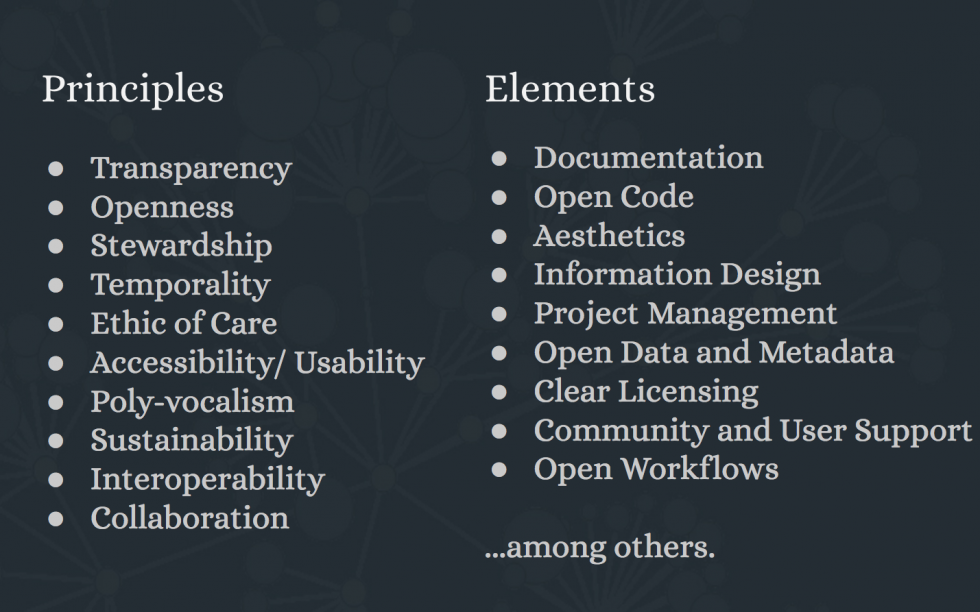

Advocacy by Design articulates a shared understanding and practice that fronts questions of how people are represented in, or are subjects of, academic work; questions of who reads and uses our work as well as those who collaborate and contribute to our work. We articulate this advocacy through particular stances on a number of interrelated concepts, we call principles. Some principles are borrowed from Shaowen Bardzell’s Feminist HCI: Taking Stock and Outlining an Agenda for Design, while others grew out of our experiences with Take Back the Archive.

These principles include within them components and elements, such metadata, project management, and licenses, to better apply principles throughout a research inquiry. Advocacy is active—an attention-based practice of asking what are we doing to foster diverse voices? What do these practices look like face-to-face? What do they look like in the things we design, build, share?

Elements are ways to make visible the principles within our workflows, interactions, and research products.

Advocacy by Design is not proscriptive, not a checklist, rather a way of practicing that invites return and reflection upon the why and how of our work.

When thinking about archives in the Anthropocene, the principles of transparency, stewardship, poly-vocalism, and ethics of care emerge as a way to enact or reflect a justice-or advocacy-based approach to archival practice.

- Transparency, meaning what is collected, by whom, why, and how clearly is that communicated to readers/users?

- Stewardship: Traditional archives have a mission to preserve materials in perpetuity

- Preservation and archival ownership are different than stewardship, which stresses the care of materials, and this care should include care for the people represented within those materials

- Poly-vocalism, which resists a single narrative and seeks to open pathways for many points of view and many points of engagement with sources.

Carol Gilligan writes, “The ethics of care starts from the premise that as humans we are inherently relational, responsive beings and the human condition is one of connectedness or interdependence. As an ethic grounded in voice and relationships, in the importance of everyone having a voice, being listened to carefully (in their own right and on their own terms) and heard with respect.” For Gilligan, a feminist ethic of care is an ethic of resistance to the injustices inherent in patriarchy (meaning the association of care and caring with women rather than with humans, the feminizing of care work, as well as the rendering of care as less important, though linked with, justice).

Ricky Punzalan and Michelle Caswell ask “What happens when we begin to think of record keepers and archivists as caregivers, bound to records creators, subjects, and users through a web of mutual responsibility?” How does this shift our collaborations with communities, scholars, archivists, and record keepers? How does an ethic of care shift how we collect, analyze, and prioritize records?

Ethics of Care provides a way to think through our responses and responsibilities and position the human condition as one of connectedness, one of interdependence, which echo’s Donna Haraway’s call for us to recognize and honor the interconnections among people, plants, animals, and the planet in an effort to create, foster, and defend places of refuge. Haraway’s play with responsibilities and being response able are helpful touchstones for thinking about archives in the Anthropocene.

I want to share three quick example of principles and elements in an existing project. Documenting the Now does a fantastic job at communicating technical infrastructure and project decisions through a variety of platforms, from newsletters to a Slack Channel to GitHub, all elements of transparency.

Further, Documenting the Now builds tools alongside the community of activists, scholars, researchers, and interested public so users are able to manage their own data and representation. Christina Harlow points to DocNow as a model for library and information professionals in opening our work of selecting, curating, and managing data and tools to the very users who are best positioned to shape and improve these practices.

Collecting in collaboration with communities is slower, more complicated, yet this practice can support our reflection on biases inherent within traditional collecting policies, particularly who decides what is valuable, worth of collecting and preserving and therefore status, funding, and place within the archive. It also means we must address what collaboration looks like and mean within the library, particularly attention to what power structures are inherent and tacit within collaborations? Ed Summers, co-PI of Doc Now, indicates that collaboration can be a source of tension-but this tension is vital because the project has a responsibility to work with communities to insure people are authentically represented, or not, within the archive.

In the second example, for the De/Post/Colonial Digital Humanities course at HILT 2015, Roopika Risam and Micha Cardenas collaborated with participants to develop a resource for designing digital humanities research with demonstrated commitments to social justice. 11 participants shared their work publically with an explicit invitation for others to contribute prompts and resources around access, material conditions, methods, ontologies and epistemologies that shape digital humanities. In their words, “The goal here is to make visible the critical and theoretical processes that subtend digital humanities practices.”

The site contains prompts, such as “How accessible is the project for people with disabilities?” “How accessible is the project in low-bandwidth environments?” “Which archives does the project use?” and “Whose voices are absent from these archives?” alongside links to practitioners and resources engaged with the issues around a particular prompt.

Users are able to comment at sentence, paragraph, or section level, extending a conversation about practice beyond the local and temporally located working group. The goal here is not to stagnate or stall a project, rather to slow down and reflect upon the ethical choices needed in the creation of digital work. The goal is to break these choices down to manageable, addressable parts. As Amy Wickner observed, Ethical tensions are addressable. While ethical considerations need to be at the center of our work, they need not prohibit this work from progressing.

I return to Moya Bailey’s article, #transform(ing)DH Writing and Research, An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics, quote “If my work and aims are not in collaboration with the communities I wish to talk with, then I’m not doing the right work. Transparency is essential for creating the kind of research that is of most use to these communities—the communities that are so graciously letting me and other scholars into their lives.”

With community collaborations, can we create and describe collections that show, offer modes of manipulation, and resist a single explanation or narrative? It is incredibly important to make visible the decisions that are made, from selection to description to discovery. These decisions are interpretive and can reinscribe erasure and exclusion, particularly when materials are gathered from those whose own cultural documentational methods are not considered valid or valuable to the institution.

An example of documentation as an element of transparency and collaboration is Project BlackLight, an open source, front-end, discovery interface for Apache Solr. Blacklight is now a part of Project Hydra, a collaboration to help institutions around the world preserve, maintain and give access to their knowledge repositories and assets.

The quickstart guide gives clear indication of the dependencies, which is great but the more exciting documentation is the Wiki. It is written in an welcoming tone with clear expectations of skillsets. Yet, if someone is interested but not experienced with Ruby there are links to resources and guides. The intention is not to reduce documentation to meet all skill-levels, but to point people towards clear avenues to best use Blacklight.

Returning to Bardzell, who asks us to attend to the broadest context of stakeholders. Within the context of information platforms and systems, could we be transparent to our communities about who is building software and in what environment, what skills are expected to best utilize these platforms and systems, and where one could acquire such skills.

Sharing documentation and access to these platforms offer doorways for users to see the most recent version, empowers people to pull the code, change it, contribute back. Can we imagine documentation that is welcoming, simple to read, that communicates how the system or platform works? Why it was decided upon? Who contributed to it? And how users may fork it, change it, contribute back to it? As well as indicate to users the labor involved in creating the system and subsequent documentation?

Returning to questions posed at the beginning, how do we grapple with the uncomfortable questions of who decides what is significant to carry forward, in whose memory is the past best preserved, how do we determine who counts as ‘we’ and by which ethical frameworks guide our efforts of preservation and future-shaping?

The following three examples point to archival possibilities in the Anthropocene, two point to alternative modes of archival practice, while the third gestures to notions of non-human ‘archival’ practices. I am particularly influenced by Jessica Marie Johnson’s digital maroon communities. It’s a big quote, but I think her comments are particularly useful in the following examples:

The digital—doing digital work—has created and facilitated insurgent and maroon knowledge creation within the ivory tower. It’s imperfect and it’s problematic—and we are all imperfect and problematic. But in that sense I think the digital humanities, or doing digital work period, has helped people create maroon—free, black, liberatory, radical—spaces in the academy. I feel like there is a tension between thinking about digital humanities as an academic construct and thinking about what people do with these tools and digital ways of thinking. DH has offered people the means and opportunity to create new communities. And this type of community building should not be overlooked; it has literally saved lives as far as I’m concerned. People—those who have felt alone or maligned or those who have been marginalized or discriminated against or bullied—have used digital tools to survive and live. That’s not academic. If there isn’t a place for this type of work within what we are talking about as digital humanities, then I think we are having a faulty conversation.

Many of the challenges and opportunities Johnson raises for the digital humanities are paralleled in archival work in a moment intensely unevenly distributed violences and protection or sanctuaries. Marisa Parham’s use of Toni Morrison’s re-memory useful here as well; memory and memory work as not totalizing but always contextualized in time and space.

This description of the Community Futures Lab comes from their facebook page:

“Community Futurisms: Time & Memory in North Philly” is a social practice, collaborative art, and ethnographic research project exploring oral histories, memories, alternative temporalities, and futures within the North Philadelphia neighborhood known as Sharswood/Blumberg. The area is currently undergoing a major redevelopment project after years of deep poverty, educational inequality, and high crime. “Community Futurisms” will document the redevelopment of Sharswood/Blumberg, through an multidisciplinary community art project that explores the intersections of futurism, literature, visual remixing, sound, and activism as art.

Community Futures Lab is a gallery, library, workshop space, time capsule, recording booth, and community center. The goal of the Community Futures Lab is to collect, preserve, and share the Sharswood-Blumberg community’s memories and stories for future generations.

In spirit with Jarrett Drake’s Abolitionist Archive, meaning community and grassroots archives which work to eradicate structures of violence as they work to imagine and implement more just structures that support equality for all people, the Community Futures Lab is working to resist displacement, and explain or contextualize the pasts, but also signal towards and shape futures.

Prominent principles include:

- Poly-vocalism—resists single gentrifying narrative, both of the completeness of such gentrification and the myriad sufferings and joys of neighborhood members; the oral history project in particular works as intervention to a single narrative, but workshops like DIY time-travel returns modes of recording stories to the individuals who make up the community

- Stewardship—while not scoping timelines for the care and maintenance of oral histories and other fruits of the CFL, there is significant attention to the care and stewardship of the community members and their stories, stewardship of the memories of the neighborhood and the processes of gentrification

As archive in the Anthropocene, Community Futures Lab reminds us to not forget Haraway’s critique of the term—Anthropocene can be too big and too universalizing to capture the local pressures exerted by capitalism; it resists what David Edward’s has named dead priorities, money, capital and profit, as it asserts living priorities—people, animals, the planet at a neighborhood-scale. Community Futures Lab is actively working to advocate real structural change (re: housing assistance and education about tenant rights) as it imagines and strives for new modes of being in the current reality of gentrification and displacement.

Future Library Project is an art, forestry, and literary project led by Katie Paterson. A tract of forest is being planted near Oslo, Norway with the intention that in 100 years, a manuscript—until then unread—will be printed using trees from the forest. Each year, a small committee of 6 select and invite an author to contribute a manuscript to be held in trust for 100 years.

Principles and elements

- Significant effort engaged in stewardship within a named timeframe, like the Community Futures Lab there is attention to both care of materials and skills; in this case, the project includes a printing press and periodic training on how to use it.

- Transparency, clear who is selecting authors, attention to rotating board members every 10 years as to avoid narrowly (rather more narrowly since it is one author per year) speak the current moment to future audiences;

The temporality of the project is compelling in that unlike the Community Futures Lab, the Future Library anticipates a near-future, but one just outside our experience.

The final possibility for considering archive in the Anthropocene are what Susan Weisner and others have termed accidental archives.

Archives of trash or ocean plastics, archives that have no formal process of selection materials, rather our contributions act as an accession strategy gone wrong. Yet, scientists, environmentalists, and others use these vast collections to anticipate future challenges, such as the effects of plastics on filter feeders.

Accidental archives are in conversation with notions of post-custodial archives—the idea that archivists will no longer physically acquire and maintain records, but that they will collaborate with communities to assist with the management of records which remain in the custody of the individuals or communities of origin. For “archive” of ocean plastics and trash, there is not a single community of origin, rather it is a shared responsibility—though, of course of unevenly distributed contributors and those who bear the costs. Accidental archives of ocean plastics highlight the primary challenge of the Anthropocene, where the protection and preservation of some ecologies and communities come at the cost to other ecologies and communities.

The lens of the Anthropocene gives us a way to look at large-scale threats and pressures and to contextualize local responses, to move between the two views attending particularly to practices of making, keeping, and utilizing of records for memory. It gives us a way to consider what our abilities to respond currently are and ways to imagine what our responses could be.

As an archivist, I am concerned about how these incredible and powerful archives will be carried forward so they may continue to speak futures into being. The collaboration between liberatory, or as Drake suggests, Abolitionist, archives and critical archivists, such as Caswell, Sangwand, and Punzalan help us connect Jessica Marie Johnson’s maroon communities of DH, in the anticipation that these archives and archival projects help us better imagine and construct more just infrastructures that resist violence, silencing, and erasure, that protect the materials from which we may speak into being many possible pasts and many possible futures. Thank you.

Works Cited

Bailey, Moya #transform(ing)DH Writing and Research, An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics, Digital Humanities Quarterly, Vol 9, No 2, 2015. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/2/000209/000209.html

Bardzell, Shaowen, “Feminist HCI: Taking Stock and Outlining an Agenda for Design,” CHI 2010, April 10-15, 2010. http://wtf.tw/ref/bardzell.pdf

Caswell, Michelle, et al. “Critical Archival Studies: An Introduction.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.50. http://libraryjuicepress.com/journals/index.php/jclis/article/view/50/0

Caswell, Michelle. “Not Just between Us: A Riposte to Mark Greene.” American Archivist 76 (2): 605–8. 2013.

Terry Cook, “Fashionable Nonsense or Professional Rebirth: Postmodernism and the Practice of Archives,” Archivaria 51 (2001): 26

Document the Now. http://www.docnow.io/ Accessed February 2, 2018

Drake, Jarrett. “Repositories of Failure: Creating Abolitionist Archives to Project Past the Punishment Paradigm” Maryland Institute of Technology in the Humanities Digital Dialogue. February 13, 2018. http://mith.umd.edu/dialogues/dd-spring-2018-jarrett-drake/

Gilligan, Carol, “Ethics of Care Interview,” Ethics of Care, June 21 2011. http://ethicsofcare.org/carol-gilligan/

Haraway, Donna, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Cthlulucene,” Environmental Humanities, Vol. 6, 2015. http://environmentalhumanities.org/arch/vol6/6.7.pdf

Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Johnson, Jessica Marie. July 23, 2016. “The Digital in the Humanities: An Interview with Jessica Marie Johnson” LA Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/digital-humanities-interview-jessica-marie-johnson/ Accessed February 2, 2018

Parham, Marisa, “Black Haunts in the Anthropocene”. http://blackhaunts.mp285.com/ Accessed February 2, 2018

Paterson, Katie. Future Library. https://www.blackquantumfuturism.com/community-futurisms Accessed February 2, 2018

Perkins, Yvonne, “Women and archival silences” Stumbling Through the Past: Delving in to History blog. Posted 09/03/2012. https://stumblingpast.com/2012/03/09/women-and-archival-silences/ Accessed February 2, 2018

Philips, Rasheedah, Camae Ayeway, Community Futures Lab project, Black Quantum Futurism. https://www.blackquantumfuturism.com/community-futurisms Accessed Feb 2, 2018

“Project Blacklight”, https://github.com/projectblacklight/blacklight/wiki#support and https://github.com/projectblacklight/blacklight/wiki/Quickstart Accessed Feb 2, 2018

Ricardo L. Punzalan and Michelle Caswell, “Critical Directions for Archival Approaches to Social Justice,” The Library Quarterly 86, no. 1 (January 2016): 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1086/684145

Ramirez, Mario H. (2015) Being Assumed Not to Be: A Critique of Whiteness as an Archival Imperative. The American Archivist: Fall/Winter 2015, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 339-356.

Risam, Roopika and Micah Cardenas, Social Justice and the Digital Humanities, 2015. http://criticaldh.roopikarisam.com/ Accessed Feb 2, 2018

Sadler, Bess and Chris Bourg, “Feminism and the Future of Library Discovery,” Code4Lib, Issue 28, April 15, 2015. http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/10425

Solli, Brit, et al. “Some Reflections on Heritage and Archaeology in the Anthropocene.” Norwegian Archaeological Review, vol. 44, no. 1, 2011, pp. 40–88., doi:10.1080/00293652.2011.572677.

Wallace, David. 2010. “Locating Agency: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Professional Ethics and Archival Morality.” Journal of Information Ethics 19 (1): 172–89.