I’m posting a short series of a lightly edited posts from of my keynote for the University of Maryland Library Research and Innovative Practice Forum. Slides and talk are available through DRUM. This is Part 3 and the final post of the series. Read Part 1 and Part 2. —Purdom

I return to Moya Bailey’s article, #transform(ing)DH Writing and Research, An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics, quote:

“If my work and aims are not in collaboration with the communities I wish to talk with, then I’m not doing the right work. Transparency is essential for creating the kind of research that is of most use to these communities—the communities that are so graciously letting me and other scholars into their lives.”

With community collaborations, can we create and describe collections that show, offer modes of manipulation, and resist a single explanation or narrative? It is incredibly important to make visible the decisions that are made, from selection to description to discovery. These decisions are interpretive and can reinscribe erasure and exclusion, particularly when materials are gathered from those whose own cultural documentational methods are not considered valid or valuable to the institution.

One example of documentation as an element of transparency and collaboration is Project BlackLight, an open source, front-end, discovery interface for Apache Solr. Blacklight is now a part of Project Hydra, a collaboration to help institutions around the world preserve, maintain and give access to their knowledge repositories and assets.

The quickstart guide gives clear indication of the dependencies, which is great but the more exciting documentation is the Wiki. It is written in an welcoming tone with clear expectations of skillsets. Yet, if someone is interested but not experienced with Ruby there are links to resources and guides. The intention is not to reduce documentation to meet all skill-levels, but to point people towards clear avenues to best use Blacklight.

Returning to Bardzell, who asks us to attend to the broadest context of stakeholders. Within the context of library platforms and systems, could we be transparent to our communities about who is building software and in what environment, what skills are expected to best utilize these platforms and systems, and where one could acquire such skills.

Sharing documentation and access to library platforms offer doorways for users to see the most recent version, empowers people to pull the code, change it, contribute back. Can we imagine library documentation that is welcoming, simple to read, that communicates how the system or platform works? Why it was decided upon? Who contributed to it? And how users may fork it, change it, contribute back to it? As well as indicate to users the labor involved in creating the system and subsequent documentation?

Particularly within the question of who contributes to the development of library software, but also extending to who makes up library committees, collaborates with students, performs outreach to campus and communities?-these questions are inherently questions of staffing, labor, and library policies.

It is time-consuming and difficult to be transparent in why and how our policies come about; it means taking down and reimagining our hiring and retention practices. As April Hathcock wrote in her 2015 article White Librarianship in Blackface: Diversity Initiatives in LIS:

“We need to make space for our diverse colleagues to thrive within the profession. In short, we need to dismantle whiteness from within LIS. We can best do that in two equally important ways: by modifying our diversity programs to attract truly diverse applicants and by mentoring early career librarians in both playing at and dismantling whiteness in LIS.”

She continues, “when we recruit for whiteness, we will get whiteness; but when we recruit for diversity, we will truly achieve diversity.” We can, with attention to our hiring and retention practices, make space for more black, brown, trans, and queer bodies to contribute to library software, library committees, and outreach efforts.

This making space is difficult—it takes time, money, effort to examine and dismantle existing practices and to imagine then build new, more equitable and just ones.

Making space, for me, means returning to the Carol Gilligan’s Ethic of Care. Gilligan’s argument that the human condition is one of connectedness, one of interdependence echo’s Donna Haraway’s call for us to recognize and honor the interconnections among people, plants, animals, and the planet in an effort to create, foster, and defend places of refuge.

For Gilligan, a feminist ethic of care is an ethic of resistance to the injustices inherent in patriarchy (meaning the association of care and caring with women rather than with humans, the feminizing of care work, as well as the rendering of care as less important, though linked with, justice). The Library is a space where this resistance and radical care work can be, and is currently, practiced.

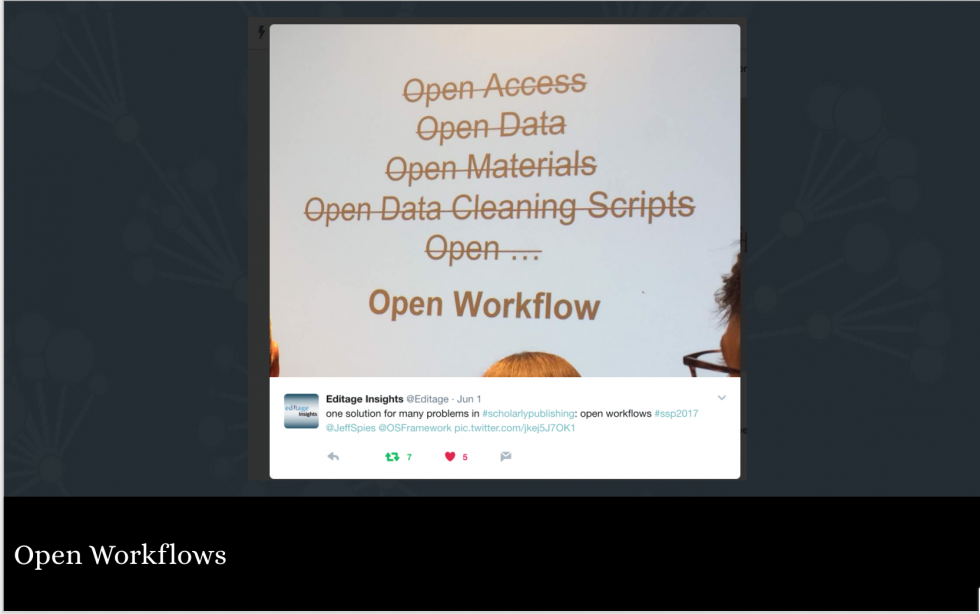

Interconnectedness is a major tenant of the Ethic of Care described by Gilligan. Within the library, the processes of what collections we buy, which collaborations we lend time to, are interconnected to issues of funding, user stats, time allocations, and a myriad of other concerns. Much of the negotiations and decisions are obscured from other departments and our patrons. One way to challenge this is to create and share open workflows.

Open Workflows, more than open data and open access (both of which are important), give scope to protocols, tools, practices, and rationales. Practicing transparency can create deeper understanding of the very real constraints libraries are working within. For example, and I think the statute of limitations has run out now . . . hopefully . . . in one of my former positions, I had a patron upset because a very expensive resource was being canceled. I sat down with this patron, walked them through the committee’s decision process. I did all the things I was not supposed to do- I shared the general the budget, shared the cost of the canceled resource (It costs about x thousand dollars per year, we have about 3 people using it), and then we worked together to identify the specifics of what they needed in order to find that information in a different database.

Open Workflows clarify the constraints an institution is working within, can detail who is responsible for making decisions, what information goes into those decisions, helps us say no to projects that are beyond the scope of the work we do (hopefully with pointers to who else on campus or within the community does accommodate that work). Moreover, openness means others can reuse it, expand it, fix it. Openness further gives us a platform to talk about the costs and effort of service.

In libraries, care on par with justice, includes educating ourselves and our collaborators ( including students, community members, staff, and faculty) about privacy online. Library Freedom Project is a partnership among librarians, technologists, attorneys, and privacy advocates which aims to address the problems of surveillance by making real the promise of intellectual freedom in libraries.Their focus is teaching librarians about surveillance threats, privacy rights and responsibilities, and digital tools to stop surveillance, with the hope to create a privacy-centric paradigm shift in libraries and the communities they serve.

The Library Freedom Project, responding to increased surveillance online, has a Privacy Toolkit for Librarians, makes clear its funders and funding model, as well as a wide-range of resources for learning and advocating for privacy online.

The mission of The Library Freedom Project is one way to enact of the Ethic of Care. Specifically, we teach others to use digital resources, teach digital literacies, but we do not make clear what data is collected or by whom or for what purposes when people use library services or through general internet use.

Could we include digital privacy workshops within the rich range of existing Teaching & Learning workshops or as a quick-start guide alongside managing data and resources within the excellent Research Commons services? How can we make transparent our own efforts to better understand governmental and corporate data gathering from our vendor services? What collaborators would we need to identify to build relationships across campus? How can we identify our own risks and communicate those out to our colleagues within the library and beyond?

One approach to such questions is to center the library as a base for grassroots activism–around digital privacy as well as endangered data. The Library is a vibrant center of intellectual life and is situated at a crossroads of campus. Positioned in this way, grassroots efforts, like those of Endangered Data Week, can activate the broad networks of collaborators spread across campus.

In the case of UMD’s Endangered Data Week, representatives from the Library, iSchool, and MITH organized an interdisciplinary panel on the complex topic of endangered data, a hands-on workshop for personal data archiving best practices, as well as hosted a webinar. These events were held in conjunction with international Endangered Data Week which is dedicated to highlighting threats to data security and preservation.

The collaboration was one of distributed labor, various members of the organizing team taking a lead on a portion of the weeks events. It relied on email and shared google docs to keep communication flowing. And importantly, this kind of collaboration can serve as a model for other grassroot efforts of interest to the Library and the Library’s communities.

A final example of Libraries enacting the Ethic of Care is UVa’s Making Noise Series hosting Overmorrow by Rachel Devorah Wood Rome, which is a sonification of gun violence in the United States. Making Noise hosted both a performance of the sonification and a discussion afterwards. The library became a space to talk about gun violence in the United States, specifically police violence against black bodies, as well as a space to reflect upon whiteness, the pitfalls of empathy in sonifying violence predominantly against black people, the role and responsibilities of white researchers engaged in anti-racist work, specifically when that anti-racist work is about violence and death. These are not easy conversations. Rachel Trapp has written about the evolution of Overmorrow and the work still to be done in order not to reinscribe violence with her work.

Libraries can be a space to elevate conversations of our interconnectedness. Taking the lead from The Crunk Feminist Collective, the library can create space of support and camaraderie by building community through fellowships, debates, challenges, and support of each other as struggle together.

As I mentioned in the beginning, the editors of the journal Salvage, wrote “The infrastructures against social misery have yet to be built.” Applying Gilligan’s ethic of care, engaging with the principles and elements of Advocacy by Design, Libraries, specifically, our library, can begin the speculative work of sketching out and practicing what those infrastructures against social misery look like. Much of this work is not speculative; As Bess Sadler and Chris Bourg assert:

The means of production for the archives of humanity are up for grabs, and within our reach is the possibility of new production methods that resist the recreation of existing patterns of exclusion and marginalization.

We can put concerns about people at the center of everything we do, inviting our patrons to be collaborators

We can work to build a vocabulary of advocacy,

We can strive to be transparent in our decision making and policies, about what service means

We can transform our hiring and retention practices

We can include codes of conduct for our conferences, communication channels, and projects.

We can use library space to foster grassroots organizing around issues like privacy and endangered data

We can use library space to talk about our anti-racist and anti-violence commitments, collaborations, and research

These are foundations to do the speculative work together, in a critically engaged way, and with an approach that is conscious of the effects of our decisions.