Hack Books: Hack What?

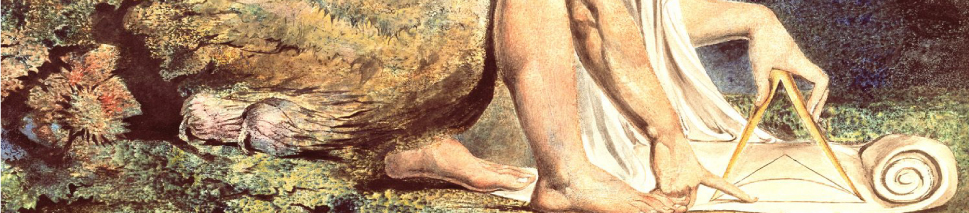

Posted by on Thursday, January 26th, 2012 at 10:40 pmI spent my bus ride home thinking about what it might mean to hack a book. I’ve seen beautiful sculptures made out of books (like these: one two three four) as well as more readable, but still fundamentally remixing acts of book hacking in the form of “altered books” like A Humument and Jonathan Safran Foer’s deliberately altered The Tree of Codes. Even more than book art, however, thinking about designing digital editions of paper books has helped me start noticing the individual mechanics of the vehicle, and it feels like outlining just what a book does is a good step toward making it do things it “shouldn’t” (i.e. hacking). Although we’re not talking about digital literature yet, it could be useful to contrast books on-screen and off if we want to start pointing to what makes a book work (or, you can check out this “Medieval Help Desk” video and think about the happy differences between scroll and book!).

Matt Kirschenbaum’s article “Bookscapes: Modeling Books in Electronic Space”* argues that contrasting books with their on-screen counterparts helps us call out the specific features important to the analog form because “books on the screen are not books, they are models of books”–and a model is made to be hacked and analyzed. Matt’s article offers a nice starting point for thinking about the features of books, identifying five affordances specific to the book:

- simultaneous random access and sequential ordering,

- volumetric (three-dimensional) storage space,

- finity/boundedness,

- the comparative possibilities offered by two facing pages (think of Folger student Shakespeare editions), and

- writeability (who hasn’t wished they could jot down notes on the PDF they’re reading online?).

As we look at how Blake hacks the book, can we add to Matt’s list of book affordances? In addition to broad characteristics, we might list specific elements such as the datedness of page numbering on the Nook or the (un?)necessary pause when “flipping” pages on a Kindle. Why were these technologies useful in books, and awkward (or nostalgic) in e-books?

*Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “Bookscapes: Modeling Books in Electronic Space”. Human-Computer Interaction Lab 25th Annual Symposium. May 29, 2008.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.

Amanda makes some very good points here, and I recommend Matt K’s article to you all–a great point of departure for our class discussion on Thursday. I’ll bring to class a copy of A Humument. I’d also like you to be thinking about the remediation of Blake’s books by the The Blake Archive. To what extent are the editors of that site hacking Blake?

How does “Jefferson’s Bible” fit into the idea of hacking a book?

It’s at the Smithsonian American History Museum now http://www.si.edu/Exhibitions/Details/Jefferson's-Bible-The-Life-and-Morals-of-Jesus-of-Nazareth-4677

It makes me think about how books like the Bible might be viewed as hacked all along. Oral tradition that is eventually written down and copied over and over again by hand–was every copier part of the security system against hacking? Or were they hacking that system? Or was it ever hacked by an outside individual? Does it have to come from the outside to count as hacking?

Copying the bible, or any text prior to the printing press, was ripe for scribal corruption, perhaps to be equated with Robert Morris’ “accidental” internet worm. Along with Jefferson’s hacking of the bible, consider the cento poem (a poem consisting only of lines from other poems). This author has hacked others’ work and appropriated it for his own means: http://poetry.about.com/gi/o.htm?zi=1/XJ&zTi=1&sdn=poetry&cdn=education&tm=9&gps=162_11_1366_673&f=10&tt=14&bt=1&bts=1&zu=http%3A//dougkirshen.com/dong/

Also, those links to book sculptures remind me of another that’s in the East Building of the National Gallery right now. It’s on the mezzanine level–lineament ball by Ann Hamilton. I’m fascinated by its list of materials: “unwound book, glass, & wood.” How can a book be unwound? Is that like hacking? I think so. I think that un-winding or re-winding a book, once wound, must be a way of hacking into it. And of course it requires physically hacking away at it, with scissors. The literal cutting and pasting makes me think of the way hands are active in such an activity, and not just eyes (I’m thinking about the Cooper and Simpson essay now). You can wind a string of words around your fingers, roll them into a ball (like the sculpture does). And typing that, I’m suddenly obsessed with my typing fingers. Better stop now.

That’s got to be the first spherical book I’ve ever seen! (I found a photo here if anyone’s interested.)

“Unwound books” makes me want to talk about analog hypertexts, since I think of them as “exploded books”… texts like Robert Coover’s “Heart Suit” (that pull apart the musculature/linkages of books) or like Ulysses (that pull apart traditional linear bookform from inside the text).

Oh good! Thanks for posting the picture. (I couldn’t find one, but I honestly didn’t look too hard.) In the museum, you can see the ball is winding from an open and cut up book sitting beside it.

Great post to start things! The book arts and (in Allison’s reply) Jefferson Bible angles are super apposite!

Thinking a little about the nature of hacking itself, while devoting energies otherwise to a post for the blog, I’m thinking a little about hacking as it is currently conceived. It’s worth more thought than I can devote to it for the moment, but it’s certainly a practice of appropriation. In our time the hacker ethos of making technology one’s own comes to us by many paths–from DIY articles in popular magazines going back many decades to the DIY philosophy of independent music companies of the 1970s and 1980s to the practice of computer programmers learning to work fluently within complex systems. To hack a book–to take a first hack at it–could be to come to fluency within the system of book-making, to appropriate the received technology of book production and printing for one’s own unique artistic vision, to appropriation of past books… to what? I would rather type a fragment to this end and put it in play than get it perfect on the first try.

I went to sleep Thursday night with the discussions from class in my mind, and began to wonder much like Allison about Jefferson’s Bible.

To judge from Tarcher / Penguin Editor Mitch Horowitz’s http://interfaithradio.org/2012/Show4 on the Public Radio Program Interfaith Voices, it does seem reasonable to see Jefferson’s project as hacking. It is certainly an appropriation, and unconventional enough to keep secret in its time. It’s also conceived in a very personal hermeneutics based in Jefferson’s conception of the natural. What doesn’t sound plausible in this hermeneutics is supernatural and subject to redaction. I’m reminded of Samuel Taylor Coleridge hashing over the ideas of organic and mechanical form in literature, at one point bringing in the chimera as a model for mechanical form: literature in which the parts just don’t fit together. Jefferson’s rework of the Bible could be imagined to be a kind of rehabilitation of a chimera.

With time drawing short I will post this, essentially fragmentary as it feels.

Pingback: Hacking vs. Altering: - Technoromanticism

Pingback: lustro piotrków