The Human Touch

Posted by on Friday, February 27th, 2015 at 12:07 pmWhen we talk about digital archives and the grand potential of digital media, a part of me cries out in protest. I love books. I love reading books. And I love buying books. There is something about the materiality of books that speaks to me. Two Christmases ago, my family purchased a Kindle for me, expecting that this device would allow me to continue my voracious reading without spending as much money or taking up as much space. Instead, I gave the Kindle to my Mother for Christmas this past year, having finally admitted that I could not abide by its digital demands.

I keep coming back to Walter Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking My Library.” It’s a beautiful work by a true bibliophile. In it, he writes, “Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.” When I hold a printed book, I am reminded of my younger self (if I have read it before) or am tempted to dream about the potential owners and path this item has taken to reach me. I own several books that are more than 100 years old, and I treasure them, less because of their contents (there are easier ways to access Kipling’s The Jungle Book, for instance) but because of the material history involved. How many hands have held this book? How many owners have lent it to friends or relatives? I know this all sounds a bit idealistic, but this is the mindset I had when class began a few weeks ago. A digital archive was a last resort, a place to find information you could not find in your well-worn copy of whatever volume you were investigating.

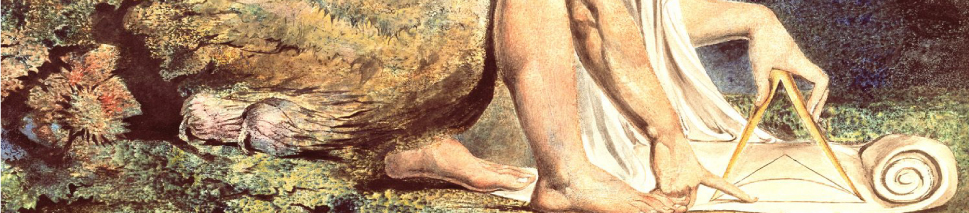

Now, after having some experience with archives — The William Blake Archive, the archival function of Romantic Circles, and a short exploration of the Shelley-Godwin Archive — my opinion has changed, albeit only slightly. The William Blake archive, in particular, serves one of the more important functions I envision for any digital trove: that of aggregation. As Neil pointed out, it was rare for Blake scholars to be able to view more than one print of Marriage of Heaven and Hell or The Book of Urizen in a lifetime. With this website, they can view nine extant copies of the same page. There are improvements to be made, of course. The aesthetic of the site, for instance, seems ill-suited to honor a man who so thoroughly combined his artistic and poetic abilities. The prints, or at least how we see them on the website, are flattened. The involved process that Blake employed (and invented) created plates with depth and, ultimately, prints with varying textures and thickness. This flatness robs the prints of some of their beauty and seems to simplify them. We are left with JPEGs of scans of books, several steps removed from the “true” article, as I see it. The Shelley-Godwin Archive then is an improvement on this method. By providing the manuscripts (of Mary Shelley, for example) and then matching those with clearer digital transcriptions, allows us to view the “true” article, the piece that most bears the imprint of a human touch. And, perhaps, that is what I most fear losing as we transition into digital archives.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.

I completely agree with Justin’s comments about the print book. I too have a strong reaction against digital works, but at the same time, I am having a hard time to explain it and, even though I try, I struggle to properly rationalize it.

Just like Justin, after having actively experiences digital platforms like the Blake Archive or the Shelley Godwin Archive, I cannot help acknowledging the multiple advantages it offers. To add to Justin’s list about the Blake Archive:

– It offers universal access to all of Blake’s works for example;

– It organizes and classifies them in order to facilitate the user’s experience;

– It serves Blake’s original purpose by acknowledging and taking advantage of technological progress.

–Blake’s original purpose by acknowledging and taking advantage of technological progress.

But, as Justin said, there are, indeed, improvements to be made:

– Regarding the very question of access, I must say that, for my part, I did not find the Blake Archive intuitive at all. On the contrary, I struggled quite a bit to find certain pages or documents.

– As Justin said: “The aesthetic of the site, for instance, seems ill-suited to honor a man who so thoroughly combined his artistic and poetic abilities”. It seems that this is directly related to another problem (one we started to mention during our presentation a few weeks ago), which concerns the question of authorship. It seems to me that the Blake Archive should honor Blake’s original artistic intentions and therefore, should be built accordingly. Yet, it is not the case with the Blake Archive. When one undertakes to edit and transform a work of art for the purpose of remediation, the original authorial intentions may be under assault, and this results in authorial displacement. Who is the author then? The approach adopted by the editors of the Blake Archive confirms this displacement: “Our aggressive determination to make these and other scholarly actions possible is authorized not by Blake’s desires but by ours, backed by the powerful electronic medium that allows us to gratify them.” (Eaves) What justifies the modification on an original work? And where is the limit? In other words, at what point does an original work lose its integrity and becomes someone else’s work? Shouldn’t the original authorial intention be absolutely respected? In the case of the Blake Archive, the purpose of assisting academics (whose goal is, paradoxically, to protect Blake’s heritage) provides the editors with sufficient ground to remodel his work at will. Therefore, considering that one of the connotations of hacking is “to appropriate”, it seems fair to state that the Blake Archive is indeed hacking Blake’s work.

In short, its seems that digital works impose a sort of distance between the reader and the text, and therefore, exclude the reader from the experience. As Justin says, you lose the “true” article. You lose the real life unique experience of confronting the artwork because you only get copies, digital replicas (which desacralizes them). I think that, in the digital space, by getting rid of the material artwork, you also lose the human.

I am always interested in this response to the digital vs. the material manifestation of the “book”. One that I have held, and still tentatively hold, but am not entirely sure why. There appears to be a problematic enigma of how we understand the authenticity of the book. How do we define the “original” or the “authentic” moment of genesis when it comes to literature? The referential point of departure for a text’s value? Do we look to the manuscript? The first publication? The first book of the first publication? Or the first idea of it? Its first vocalization? Does it reside in the author, dead or alive? I’m not sure. I’d like to say that authenticity is often, if not always, inscrutable. But, as Justin puts it, it may not be about objective authenticity at all. It could be an infusion of memory; a subjective experience of memory that has been imbued on the material and materiality of the book. But, we don’t tend to reflect on the actual material, only the ideas and language contained within it. We don’t see the almost infinite amount of nothingness that exists between the concrete matter of the material in which we place our faith. We experience the book as materially whole, even though it’s anything but. Material, like the virtual, is predominantly light, yet aural.

To mirror Justin’s own invocation of Benjamin, I always come back to his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. While Benjamin sees the distinct turn away from a particular art’s “aura”, originality, or authenticity as a result of modern film and photography, I have always wondered why it differs so much from the supposed authenticity of reproduced, material books. What Aristotelian “substance” do we find in the materiality of the book that we don’t find in its digital form? In the digital image? Like Manon says, do we lose the “human”? And if the material book’s authenticity comes from it being an extension of memory, then whose memory are we seeing? The individual’s memory or a historical collective of memory like Blade Runner’s replicants? When Rachael says she remembers learning to play the piano she is unsure if that is the memory of Tyrell’s niece or her own. What makes our memories ours? Is it just that we remember them? What makes them human or even humans human? And by extension, the certainty we find in the historical memory of the book? I don’t have an answer for any of these questions. I see something different in the digital form of the book versus the material, but, besides more mobility of its form, I’m at a loss to know for certain what makes one more “human” than the other.

Hi Justin,

I really enjoyed reading your post. I feel like what you’re pointing at is a divide between our ‘material expectations’ and what we might call our ‘digital expectations.’ I similarly fell that oftentimes, these two notions are conflated. Receiving the ‘gift of the Kindle’ can never satisfy our desire to read, hold, smell, and spill coffee on the book. When I read a Kindle (I don’t–sorry–although I have), I cannot stick my paper notes on the pages, I couldn’t be annoyed by ‘dog-eared’ pages from a previous reader, and I certainly couldn’t add it’s beautiful cover onto my cramped bookshelf.

On the other hand, Justin, you point out some of the merits of digital resources, and the many ways that collections like the Blake Archive can enhance our understanding of print culture, the Romantic Period, and modes of composition. To me, it seems that digital tools and hardware can never replace our print desires/expectations, nor should they try to. Instead, our own expectations should be qualified and informed by what the merits of various formats/hybridized writing surfaces permit.

Although I don’t have a kindle or iPad for reading, I feel as if I’m constantly on the go, and my day is occupied reading across various writing surfaces. I wake up and read the news on my phone. I shift my attention to my inbox on my laptop to quickly breeze through emails and clear my queue. Then I divert my full attention to the printed page, where I often (although not always) prefer to read critical articles–it’s the format where I’m least distracted by any number of other tasks I might engage with on this writing/reading surface (the laptop screen). Sometimes I project my writing/reading surface on a television screen or projector, other times I shut it quickly to switch my attention completely–rebooting my brain, as it were.

Amazon can’t sell us one more commodity to rule them all, and replace our need for everything else in our libraries, bookshelves, bags/boxes filled with current and old pieces of technology, or technology recycle bins of all of our devices we cannot/do not use anymore. Perhaps we should resist attempts to further commodify and control our reading/writing surfaces and texts, but we might also keenly note and take advantage of the unique ways that these reading/writing surfaces can permit new modes of navigation, scholarly collaboration, and collective annotation. Thanks, Justin, for the great post and food for thought!