“The hinges, marks of separation and meeting, remain like quotes around a missing presence.” -Heather McHugh “Essay at Saying”

At the beginning of the semester, we discussed the identity of the “Book”. The Romantic ideal that seems to attach itself to a uniformly understood construction of material narrative. We attempted to understand exactly what the “Book” might be and in what forms might it manifest. Is there such thing as the “Book”, or is it merely a placeholder term for an unformed, ever changing notion of how a narrative is presented to us? The digital push in the humanities has been an attempt to dislodge the formerly static idea of the “Book” from its historically material constraints, i.e. paper, bindings, the spine, ink. However, revisiting works such as Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” and its unusual formulation at the time of its publications proffers a more historically complicated notion of the “Book” than we might have first imagined or would entirely attribute to digital humanities alone. Blake’s etching method (relief etching) and its painstaking process of disintegrating away the unprotected metal until only the “illuminated” remained can undoubtedly be hailed as a “hacking” of sorts. His unconventional method of printing bypassed the contemporary method of book printing for both his time and ours.

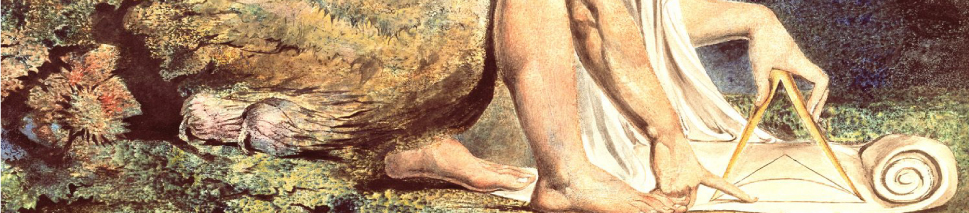

While book “hacking” has been far more common in today’s print culture, which can be seen often times in the benign form of children’s literature like The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle, postmodern literature, or, more recently, digital literature (hypertext narratives), the resilient moniker of “Book” still remains. In regard to hypertext fiction like Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, however, the stability of the “Book” begins to slightly waver. Citationally, as I have done in the last sentence (and this one), Patchwork Girl continues to be represented as a book for purposes of academic clarity, but any discussion of its formal structure would hesitate to apply such a seemingly inapplicable term to it. Like her monster, Jackson’s Patchwork Girl is an amalgamation of parts yet still a whole; it is a world(s) (a)part, comprised of disjunctive frames of narrative that are attached to each other formalistically (hypertext), but only by way of interactive, sub-formal access (clicking on the hypertext). It is what I’d like to call hinge narration. Unlike non-narrative hypertext such as Wikipedia pages or social media hyperlinks, which I would deem more a system of hypertextual information than narrative, hinge narration posits its own need for artistic conclusion, but more ephemerally it helps enact a certain form of self-identification that “hinges” on narrative closure. Hinge narration works, like postmodern art, as a way to show how it observes, not necessarily what it observes. Formalistically, and in relation to traditional, material book narratives, Patchwork Girl illuminates the passages (understood as the “quilt” passages of the text and the immaterial connections between them) of artistic narrative. The “map” in the Storyscape of Patchwork Girl literally shows the passages to the narrative passages; it makes obvious what is not obvious in normative narrative construction (the material book). We see the stitches which comprise the body of the text, the “scars” that are shown remind us of those hidden by past bodies. Through creating her “monster”, Jackson unveils the negative space of narrative; the jagged, appositional relations of letters, words, sentences, and ideas that we make within our minds while reading. The “hinges” come to the surface and, furthermore, show us that the narrative door is capable of being closed and open simultaneously. We can take each “quilt” or rectangular frame as an enclosed passage of writing and as a point of departure. Yet, more so, these illuminated “hinges” invoke the memory of narrative as well. It is not enough to simply follow the passages set forth for us but to recognize that Jackson’s hinge narrative recollects the past by embarking on a genealogical endeavor to unearth the dead (Mary Shelley), reanimate it within a new body of textuality, force a return to our own reading past and reading the past itself by quoting other readers, and concluding somewhere/anywhere within the passages of time and its narrative. Indeed, in order for it to perform any act of self-identification or presence (present), it must find its own narrative end/conclusion in the conclusion of the past, but as Faulkner said and Jackson enacts: “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Thus, that closure may come in one, few, or all of those quilted passages or even with the image of the women herself , which we find –

At the beginning