THE RIVER KIby Ariyoshi SawakoSite Ed. note: Why this Novel? Excerpts from the last part of Ariyoshi Sawako's novel, The River Ki (pp. 201-243), published very early in the author's career, have been selected here as a rare fictional portrayal by a major Japanese author in English translation of the Pacific War and foreign occupation as experienced by civilians (another is her 1963 novel, Incense and Flowers, but not yet translated and not as personal). It is also thought in part to mirror the author's own life and upbringing.

The narrative, a family saga, is divided into three parts and centers on three generations of women: Hana, her daughter Fumio, and granddaughter Hanako. The time span is from the late 1890s to the mid 1950s. Hana is the dominant character running throughout the novel from her youth and marriage to matriarchy, old age, and death. All three women are well educated for their times, Hana at a local junior college; Fumio at a new women's junior college in Tokyo; and Hanako in Occupied Tokyo as women's junior colleges expanded into colleges and universities. In the opening stages of the novel, the Matani family of rural landowners enjoy social esteem and material comfort, if not great wealth. Gradually, however, the family fortunes decline. Land reform in Occupied Japan will deliver the final blow. The narrative also serves as a key to Ariyoshi's own reflections on Japan at war and postwar reforms and reconstruction as well as the institution of the family. Among questions for the reader is the degree to which she presents Japan as aggressor, deals with civilian complicity in the war effort, or resonates with postwar social issues and democratization. Are the characters perhaps more engrossed in family loss than in issues of war responsibility?

A reminder: these are excerpts. They hint at, but cannot replace, a reading of the complete text and its multiple characters and concerns.

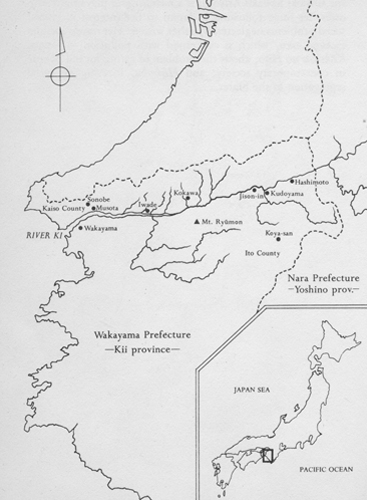

Story up to 1941. As indicated, there are many resemblances in the novel's characters to Ariyoshi's family and to her own youth and upbringing. The character of Hana, who marries into the Matani family in 1898, at the late age of twenty-two, is presented as a good wife/wise mother, a slogan which is explicitly mentioned only once in the novel but which became popular in late Meiji Japan and defined a potent, though changing, ideal for later generations of women of all social classes. The ie (patriarchal household modeled upon upper samurai families of late Edo Japan), which was legalized in the Civil Code of 1898 and abolished in the revised code of 1947, is not directly mentioned but is essential background knowledge to a full understanding of the novel's gender and social history and the legal bind of wives and second sons. Hana's young husband, Matani Keisaku, a village headman and heir to valuable land, had been chosen as a groom by her grandmother, who acted as the real go-between in the marriage, and not her father. Though somewhat lower on the social scale than Hana's birth family, Keisaku was singled out for his intelligence and promise as a leader in a prosperous rural community. Over time, there is a shift from the countryside to Osaka and Tokyo as Keisuke becomes a successful politician for the Seiyukai Party, rising from the prefectural assembly to the lower house of the national Diet. True to his village roots, he continues to provide leadership and support to local agricultural and water conservation associations. To settle a feud with his younger brother, he gives him part of the Matani land and lets him set up a branch family. Hana is a dutiful and elegant wife who gives birth to five children, is aware of but bears her husband's infidelities, and preserves the family's good name. She loves reading old Japanese literature, playing the koto, and practicing the arts of calligraphy and tea ceremony.

Hana's first child, a son, Seiichirō, is followed by a daughter, Fumio, who in her teenage and college years, early 20th century Japan, will be a great trial to her mother, rebelling against the classical arts and feminine virtues. Often disobedient and rude, she has little taste for high fashion or fine possessions. Fumio apparently is in part modeled on Ariyoshi's own mother. Before marriage, she is one of the Taisho era's modern girls and in college writes for a student feminist magazine. After marriage in 1925 to a man of her choice (or so she thinks), Harumi Eiji, a banker, Fumio soon becomes a mother but not in the mold of Hana. She asserts that she and her husband are equals but is, in her way, devoted to him. In the late 1920s and 1930s, she lives in Shanghai, Indonesia, and Tokyo, wherever her husband's career takes the family. Her daughter, the character Hanako, is born in 1931 in Wakayama, in the same year and place of Ariyoshi's own birth. Hanako's father is employed in the foreign branch of a Japanese bank, as was her own father. This character goes to Indonesia as a child, as did Ariyoshi, and returns with her parents to Japan before the outbreak of the Pacific War. The escalation of Japanese aggression in China and Southeast Asia, Japan's loss at Nomonhan on the Manchurian-Mongolian border to Soviet Russia, the austerities of total war with China, and women's patriotic activities, such as sewing 1000 stitch belts for soldiers to wear as good luck charms, become background themes to daily family life.

Entry Point. We pick up the story in Tokyo, in the immediate aftermath of the Emperor's Rescript declaring war on Britain and the United States, December 8, 1941 (p. 201, 1980 English translation). At this point, says the narrator: "The pacifist had no other recourse than to become loyal and brave subjects." Hana's husband had died suddenly of a heart attack two years earlier, and she was once again living in his home village of Musota and overseeing production on the remaining rice lands. Her eldest son, Seiichirō, long-since married and childless, had less ambition than his father and seemed content with his lot as a bank employee in Osaka and not unduly concerned about continuing the Matani household. Hana's youngest son, Tomokazu, who was engaged to marry, had received his army draft notice. The following spring, 1942, Hana traveled to Fumio's home in Tokyo for the wedding and was greatly saddened by the necessary wartime austerity of the ceremony.

..... FUMIO SPEAKS:

"You're so old-fashioned, Mother. Don't you realize that a state of emergency exists throughout the entire world? The institution of the family is about to be totally abolished."

Dressed in trousers that had been Eiji's golf knickerbockers, Fumio was on duty as a member of the Neighborhood Association. She held in her hand some circulars on the assignment of soldiers' comfort kits and on air raid drills and appeared to be in a highly agitated emotional state. She had once been a staunch liberal. However, with the outbreak of war she had been completely transformed into a brave woman supporting fully the Japanese cause. But Eiji had spent many years abroad and was very pessimistic about the war.

"Everyone talks about the Greater East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere, but the countries under Japanese military control have been thrown into utter confusion, Mother. If we were honest, we would call it the Greater East Asian Co-poverty Sphere."

"These are terrible times indeed. I'm afraid one thing simply led to another."

"But the war will soon be over."

"What makes you say that?"

"I'd be called a traitor if I said this outside the house, but I know Japan will be defeated in the end."

"Then it must be true."

"Has anyone else said the same thing?"

"Yes. Seiichirō. Kōsaku also said Japan would be defeated and was roughed up by members of the Young Men's Association."

"That doesn't surprise me."

"Fumio isn't the only woman who keeps hoping that the war will end in victory. It's far more gallant to do one's best to win than to do nothing at all because one is so certain of being defeated."

Eiji stared from behind his glasses. He had caught a glimpse of Hana's courage, which Fumio had inherited. Since becoming his wife, Fumio

had demanded much of her husband. She also possessed the tremendous will to make her husband live up to her ideal concept of a husband rather than merely observing him and gauging his ability. Despite her rebelliousness toward her mother, Hana's blood ran in her veins.

Hana had made her way to Tokyo for Tomokazu's wedding and was staying with the Harumis. The house was indeed much larger than the one in Ōmori. Nonetheless, the housecleaning had been sadly neglected, for the maids had been commandeered. The sitting room on the second floor, prepared for Hana in great haste, was in a mess. There were no flowers in the vase in the alcove. Hana picked up the vase to study it in detail and saw that it

was of fine porcelain. It was yellowish white with an indigo design and reminded her of Sung vases and Korean porcelain of the Yi Dynasty.

"It's Sawankhalok porcelain," explained Hanako, who followed her grandmother about like a shadow. The art dealers told us that it had been dug out of an old grave in Java. I interpreted for my parents in Malay when they bought the vase."

Hana realized at once that it was in fact highly prized Thai porcelain called Sunkoro by Japanese antique collectors. It came as a surprise to her that Eiji and Fumio had begun to take an interest in antiques. Hanako opened a cupboard in the split shelf and announced:

"We have lots more."

To entertain her grandmother, Hanako took out the objects one by one. She had her listen to the clear, bell-like sound that the porcelain gave off when she flicked her fingernail against it.

Hana marveled that Fumio, who had been trying to cut herself off so completely from the past, should have a daughter with a genuine affection for the things of the past.”

Hana is so delighted with her granddaughter that she offers to buy Hanako a kimono. They go off to the famed Mitsukoshi department store on the Ginza.

The sale of kimonos of figured silk had obviously been banned. Hana, who was not known in Tokyo as she was in Osaka, could do no better than select a roll of silk crape with a design of white peonies on a darkish pink ground. When she stretched the material across Hanako's back, the pink color brightened the girl's white cheeks and camouflaged her pale looks. Hana then bought a roll of Ōshima pongee for a haori to go with the kimono. The pongee was ten times more expensive than a roll of silk crape, but Hanako, who knew nothing about the true value of kimono material, preferred the silk crape with the peony design and clasped it tightly to her as they left the department store.

The two women made their way out between the stone lions standing guard at the main entrance and strolled down the street. As they

approached the Nihombashi intersection, they

were stopped by a middle-aged woman whose kimono sleeves were tied back with a sash on which the characters "Japanese Women's Association" were written. The woman, who was wearing a dark kimono and had her hair drawn back in a bun, said in a dry voice:

"Please read this."

There was not a flicker of emotion on her face as she handed Hana a leaflet. Printed in bold letters on paper the size of a postcard were

the words:We must fight to the finish! Please shorten your kimono sleeves at once!

The Japanese Women's Association Tokyo Branch "What does it say, Grandmother?" asked Hanako, trying to read the words. But Hana shook her head and tucked the leaflet into her sash.

"Hanako, let's go home."

Hanako romped about in the taxi they had taken, enjoying its luxurious atmosphere, and thought back to her life in Java when her family had a private car. Hana, on the other hand, was deep in thought. Twisting a white handkerchief which she had taken out of her one-foot-three-inch-long

sleeve, she wondered how material cut off from kimono sleeves could possibly be of any use. That sort of pedantry was more than she could swallow.

Here, Ariyoshi’s Pacific War battle chronology needs some clarification. After the end of the six-month air, land, and sea Battle of Guadalcanal in early 1943, there was little for the Japanese military to celebrate. Production of war material could not begin to match or outpace the United States. Over the summer of 1944, the Marianas, only 1500 miles from Japan, were lost. American forces under General Douglas MacArthur returned to the Philippines, beginning with the island of Leyte in October 1944 and Luzon in January 1945. Air warfare came to the Japanese home islands in late 1944 and ground warfare to Okinawa in April 1945. As Ariyoshi presents those years:

Eiji had insisted that there was no need to evacuate his family, so sure was he of Japan's imminent defeat. However, the war situation worsened and the Japanese military persevered longer than he

thought they would. Eiji became more pessimistic than ever. Tomokazu, now a second lieutenant, came to visit the Harumis.

"You know, Eiji, Japan no longer possesses a single aircraft carrier," Tomokazu said grimly. He had, in fact, just divulged a military secret.

Eiji looked pale.

"Will we have to fight to the finish on Japanese soil then?"

"Yes. The army is insisting on it, although the navy disagrees strongly."

The war front in the South Pacific was already closing in on the home islands. The Imperial Headquarters had issued a cormmuniquè which

stated that Guadalcanal had been the turning point in favor of the Japanese, but most people interpreted the bloody battle as a retreat. Before long the annihilation of the forces defending Attu Island was reported.

People were shouting hysterically: "Fight to the finish on Japanese soil! A hundred million brave lives lost." In late autumn of 1943, Eiji and Fumio finally decided to evacuate their children. By that time half of Hanako's classmates had transferred to schools in the countryside.

Kazuhiko [Fumio’s son] was enrolled in the Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University. The draft exemption—the last privilege permitted to students—had been extended to the autumn and then terminated. It was therefore not known when college students would be drafted. Fumio, who claimed to care little for the family, nonetheless remained behind in Tokyo with Kazuhiko, in deference to his position as eldest son.

Fumio sends her other two children, including Hanako, to stay with Hana in the village of Musota. In all, Hana had the care of five of her grandchildren, ages five to fourteen. No adult men were present. Life for her was “hectic.” Except for long-time servant Oichi, she had little help with the housework since the wives of the tenant farmers had to take over farm labor for their soldier husbands. Her childless first son remained in Osaka. The first child of her recently married second son, a daughter, was in the care of her son’s wife. In essence, Hana presided over a matrilineal line and was deeply uncomfortable with this outcome.

At this critical stage of the war, those gathered about her were her daughters and their children.

The matrilineal line. The woman's family. Hana had observed at first hand this strange phenomenon but had been unable to explain it as precisely as Fumio had. Hana had firmly believed in and had herself lived according to the precept that a woman severed her ties with her parents once she married. As a younger woman, she could never have returned to the Kimotos with her husband, even if a natural calamity had devastated Musota.

Indeed, a great change had taken place. Hana felt that she too had changed. But her own upbringing made it impossible for her to keep up

with the times like Fumio. It was one thing for the head of the family to be buffeted around by the affairs of the day, but Hana knew her place was at home. She would remain quietly ensconced in the sitting room until the sturdy beams started cracking and the house itself collapsed...

Hanako enrolled in Wakayama Girls' School. She set out for the city every morning with her first aid kit slung over her right shoulder and her air raid hood over her left. Hana, Fumio, and now Hanako had all studied at the school. Hana, her hair combed up in a young girl's parted hairdo and dressed in a long-sleeved kimono, had attended the school fifty years earlier. Twenty years ago, Fumio in a hakama with white trimmings had attended the school. And now Hanako, dressed in pantaloons, was studying at her mother's and grandmother's alma mater.

Every morning the students lined up in the school yard for the roll call, the flag-raising ceremony, and the reading of the Imperial Rescript declaring war. The girls then marched in military fashion to their classrooms, where not a book was to be seen. Everyone was a member of the Students' Patriotic Corps. Day after day in the classroom building which had been turned into a sewing factory, Hanako was made to sew collars on khaki uniforms. It was an assembly line method of production: those who sewed sleeves sewed only sleeves, while others sewed only trousers, or pockets, buttons, or buttonholes. All day the girls were kept at this work.

Hanako is presented as a sickly and somewhat spoiled child. She hates the sewing and rules of the Students’ Patriotic Corps, misses school with the excuse of fever but suffers a reprimand from the teacher. Even her doting grandmother punishes her for a crying jag and saying she would rather be killed by the fire raids in Tokyo than stay in Musota.

In the spring of 1945 the house in Tokyo which Eiji had bought was bombed and burned to the ground. The family fled to the home of Eiji's aunt. In hot pursuit came a draft notice for Kazuhiko.

"Mother, I told him not to do anything rash, like being the first to charge or trying to distinguish himself. I also begged him to come back alive no matter what," said Fumio, going over with Hana in Musota what she had told her son when she saw him off. Eiji had declared that he would stay with Shōkin Bank until the end, which was, after all, his duty as an employee, and remained in Tokyo. As for Fumio, only once the Harumis had been burned out of their home and Kazuhiko drafted into the army, did she finally join her mother in Musota.

"You were perfectly right. I say the same thing to the young men who come to see me before going into battle. How can one wish anyone's death?"

"Mother, what do you think will happen to Japan? Wakayama is still peaceful, but it's like hell on earth in Tokyo."

"These are indeed terrible times."...

Fumio had remarked that Wakayama was peaceful. But, beginning in June, Wakayama City became the target of frequent bombing raids. In the dead of night on July 10, the city sustained a massive bombing attack and was practically razed to the ground. That night was a night of great confusion even in Musota.

"The air raid shelter won't do!"

"Get your things and run!"

"Take to the hills!"

The leaders of the Neighborhood Association ran frantically about the village calling out individual names. Hana held on tightly to Hanako's hand and Fumio and Oichi each took hold of two of the children. They all raced along the footpath through the rice paddies past Shin'ike and in the general direction of Kitayama.

"Look! The city's burning."

"Why, it looks so close! I wonder if the fire will spread to Musota."

"It's hard to tell."

Looking from Musota, Wakayama City appeared like a sea of flames. Within this area of red, the castle became a dark shadow and then itself turned red as the flames flickered up to the tower.

"Oh, the castle . . . ," gasped Fumio. In that same instant Hana, too, noticed that the castle had caught fire. The tower was spouting flames which shot up to the sky. Then, a moment later, the castle crashed to the ground.

"Grandmother!" cried Hanako in alarm as Hana, who had been holding her hand, staggered and fell to her knees.

"I'm all right," said Hana in a firm voice.

In the small villages outside Wakayama City that had escaped war damage, the landowners' livelihood remained in a state of collapse long after the surrender. But in the war-ravaged cities people did their best to forge a new life for themselves. Meanwhile, Hana remained idle in Musota.

Utae, whose home in Osaka had not sustained any damage, came immediately to fetch her children and carried back some rice with her. Eiji, whose house had been burned to the ground, summoned his family to Tokyo in the spring of the following year. As for Kazuhiko, he had joined a corps without any weapons. Shortly before being demobilized without sustaining a single wound, he had been digging foxholes along a beach in the Bōsō Peninsula. Eiji became a trustee of Shōkin Bank when it was dissolved. As a result of soaring inflation and frozen bank counts, he went through a period of hardship, ultimately losing all that he owned.

Juice and sugar were rationed as a substitute for rice and in order to obtain enough food to live on, there was little choice but to barter one's possessions. Fumio, Kazuhiko, and Hanako survived from one day to the next. There had been no time during the hectic war years to have a kimono sewn from the material Hana had bought for her granddaughter. The lovely material had been sent along with their things from Tokyo to Wakayama, then from Wakayama back again to Tokyo. It was traded for food before Hanako had a chance to see it become a kimono.

Hanako went shopping with her mother to Nerima in the west of Tokyo and saw before her eyes the colorful silk crape with its peony design exchanged for a few pounds of barley. She called silently on her grandmother as she watched the brown, gnarled fingers of a farm woman unroll the lovely material and examine the colorful design. Hanako had desperately wanted to keep it as a souvenir of their shopping excursion to Mitsukoshi during the war. The broken pieces of Sawankhalok porcelain lay scattered in the scorched earth. And now this precious gift was about to be handed over to a complete stranger. It hurt Hanako to realize that, young as she was, all that remained now were memories.

"People talk of food, clothing, and shelter in one breath, but don't forget, Hanako, that food is by far the most important of the three."

Hanako would not be consoled—even though she was well aware of her mother's attempts to convince her that it was wrong to be sentimental about a luxurious roll of material when they were practically starving.

"I wonder how Grandmother would feel about this."

"Naturally, there would be other things to sell if we were in Musota. If you had remained there, you would never have had a taste of harsh reality."

Hanako did not wish to face the reality of having to tote barley and sweet potatoes. She expected her mother to express her sorrow at having been forced to sell her daughter's clothing. Her grandmother would surely grieve to learn that the fine material had been traded for food. She would be the best judge as to which was more painful from a woman's point of view: to part with antiques or to part with one's kimonos.

Fumio glanced timidly at her daughter who had sunk into a moody silence. She had traded the kimono material because of the impoverished state the Harumis had been reduced to by war. Nevertheless, she felt uneasy. Never having formed a deep attachment to her own clothes, Fumio did not feel too sad about parting with them. But, as a parent, it was painful to have to sell that which by rights belonged to her daughter.

Fumio remained silent to avoid further strain in her relationship with Hanako. So distressed was she by the poverty which had forced her to trade clothing for food that she was unable to articulate her feelings.

The postwar destitution of the Harumis is stressed rather than the political, legal, and educational reforms of the Occupation or questions of war crimes and war guilt. There is no mention of the new Constitution of 1947 or of the revised Civil Code which prescribed equal inheritance rights to wives and younger sons. The one exception is land reform, and this is seen from the point of view of a former landowner rather than of peasants or tenant farmers. Under severe pressure from Occupation authorities, redistribution of land had taken place by 1949. Hana lives on in worse straits, still attended by her long-time servant, Oichi (ten years younger), and, says the narrator, “resigned to her fate.”

Before the war, she had been in a position to send not only rice but clothes and bedding as well, Hana thought as she took up newspaper. She was very much distressed to learn about her daughter's troubles but was also painfully aware of the fact that the Matani family was no loner wealthy. The farmlands had been confiscated, and the tenant farmers released from their obligations. Landowners without land that they themselves cultivated had to live on rations in the same manner as city dwellers. Seiichirō and Utae came from Osaka to buy rice. The villagers, feeling obligated to Hana, could not very well sell the rice at unfair black market prices, but they were very reluctant to dole out a large quantity.

"Isn't it infuriating, Madame?" asked Oichi in a loud voice. "They say that Matsu's son in Misegaito owns five wristwatches."

"People from the city probably came to trade them for food."

"But there's such a thing as a man's place in society. What good are five wristwatches to a farmer? It's ridiculous!"

"You must remember, Oichi, that the farmers are forced to barter. Blaming Matsu's son will do no good."

"I'm not blaming anyone in particular. I'm just infuriated by this absurd world. These are difficult times, but it's absurd that Madame Chōkui should be eating rice mixed with barley."

"Japan has been defeated in war, Oichi. No one today pays any attention to names like Ch?kui and Matani. Some people have had their houses burned down, others have lost a member of the family. Still others have suffered terribly from the atomic bomb. When I think of such unfortunate people, I really have nothing to complain about."

"But Musota escaped war damage. In fact, no other place has become as well-off as Musota since the end of the war. We're near the city and we're near the mountains, and so people come here to buy their rice and they come here to buy timber and they don't even stop to think of the price. The ones who are making money now are the farmers around here and they used to be tenant farmers of the Matani family. But look at them now, the upstarts, declaring that landowners were members of the exploiting class!"

"Fumio said the same thing thirty years ago. That idea isn't exactly new, you know."

"But why must they pick on the landowners? Look at your brother-in-law. He's making a tremendous profit because his trees sell so well"

Hana’s seventy year old brother-in-law, Kōsaku, who survived his brother and managed to make money in the wake of land reform, comes by for a visit [it is perhaps 1949 or 1950] and to bring some presents. He sees that she is reading the epic military tale of early medieval Japan, "The Tales of the Heike."

Kōsaku stared pensively at the book on Hana's lap. He seemed to be thinking about what to say next.

"That's an old classic you have there. Have you been comparing the fate of the Heike with that of the Matani family?"

"Oh, no. It's just that there's nothing else for an old woman to do but read."

"A number of new magazines are being published now. I'll bring you a few the next time I come."

"Thank you. I'd like very much to borrow a few."

The next day Kōsaku came with two large bundles, one in each hand, and set them down on the veranda. He unwrapped one of the bundles, which contained over ten magazines. Besides the new issues of Kaizō

and Chūō Kōron, there were several new magazines, such as Sekai,

Ningen, and Tembō. Hana was glad that magazines were being revived, but she was more impressed by Kōsaku's financial ability to subscribe to them. Turning one of the magazines over to check the price, she saw that it was far more expensive than she had imagined. People living in a place like Musota were not affected as much by inflation as were people living in the city.

"Why are you so surprised?"

"These magazines are so expensive!"

"If you're surprised by the price, you'll be even more surprised by what's inside. We're in for an even worse time than the war."

Before leaving, Kōsaku untied the other bundle.

"I've brought you some eggs. It'd be a shame to let them rot at home."

It was because Kōsaku spoke like this that Oichi felt disgusted. Unable to close his eyes to Hana's impoverished state, he tried to show his goodwill in this manner. Kōsaku had always spoken sharply, as though he felt compelled to be perverse.

"Be sure you're well nourished before you begin reading these magazines. You have to maintain a healthy balance between the spirit and the flesh, you know. These magazines will not provide you with any nourishment."

Touched by his thoughtful concern for her well-being, Hana meekly accepted his presents. Leading an uneventful life with Oichi in the huge mansion, Hana feared that her mind and body had atrophied. With the younger members of the family busy earning enough money to live on, Hana could well understand Kōsaku's strong feelings about the old taking care of each other.

After Kōsaku had left, Hana picked up one of the eggs. She tapped the eggshell with a jade hair ornament from her chignon. Once she had managed to pierce a tiny hole, she quickly broke the membrane with her finger and put the egg to her mouth. The egg white combined with the yellow yolk tasted sweet. As she swallowed the mixture, she felt the nourishment Kōsaku had mentioned run through her body. Hana helped herself to another egg. Having obediently carried out her brother-in-law's prescription, she began to read the first page of Ningen.

"Madame, it's dark outside and you're still so engrossed," remarked Oichi, switching on the light as she entered the room with the dinner tray. Due to the food shortage, the wall of formality between the two women had crumbled considerably. Oichi's speech was not as formal as it had been before the war, and Hana addressed Oichi far too politely for a woman talking to her servant. One reason for this change in attitude was that Hana felt apologetic about being unable to do enough for Oichi. After all, she had practically dragged Oichi home with her, never dreaming that she would one day find herself in such reduced circumstances. On her part, Oichi had come to regard her mistress, who had grown old graciously, as a dear friend to be looked after with love and tenderness.

"Oichi, see what Kōsaku has brought me."

"Why, they're just old magazines."

"But I can't afford to buy any. How much do you think a single volume costs?"

On Hana's dinner tray, there were two varieties of bean curd, a sardine and parsley broth, a Chinese cabbage which Oichi had grown, and pickled eggplants. Oichi served Hana rice mixed with barley in a bowl with a morning glory design, serving her just like a maid in attendance upon her mistress. Their relationship was no longer as formal, but Oichi adamantly refused to take her meals with her mistress, however often Hana urged her to.

Half-way through the meal, Hana becomes dizzy and blames this not on the meager dinner but on the magazines. Her subsequent ruminations on her family lead her to think of granddaughter Hanako, who, parallel to Aryiyoshi’s own life, is majoring in English in college and has suffered the loss of her father.

The magazines were full of

erotic stories with many a lurid turn of phrase. Hana had been very shocked.

In an effort to understand postwar Japan, Hana read these magazines and found herself confused and exhausted by their unbridled attacks and wondering why the magazines sold at all. She was both amazed and displeased that Kōsaku bought such trash. Hana found it unforgivable that there should be such a gulf between the intellectual level of the critical essays and the low quality of the fiction in the same magazine. Realizing that the elegance and refinement which she so appreciated in literature had disappeared altogether in modern Japan, Hana felt herself drained of all her vigor.

Ume had died two years after the surrender. Kōsaku now lived with his son, Eisuke, and several grandchildren. As she lay in bed, Hana thought of how her family had changed, of the deaths and of the young additions to her family. She suddenly wondered what Hanako, who was in Tokyo, was thinking about, for among the grandchildren who had lived with her during the war, Hanako was the only one who wrote to her regularly. Eiji, whose heavy drinking had finally taken its toll, had died unexpectedly this past summer. He had lacked the strength to survive in the difficult postwar period.

Dear Grandmother, How are you? As I write to you from our little house in Tokyo surrounded by poverty, I wonder why I think back so fondly to the life I led in Wakayama. In those awful years during the war and after the surrender, we had a struggle finding enough food even in Musota. And I was busy in the Students' Patriotic Corps, sifting through ruined houses and growing sweet potatoes. I never even had any chance to enjoy myself in all that time. And yet I look back on Wakayama with great fondness. Is it because I was born there? Or maybe it's because, while life in Musota during the war was just as hard as in Tokyo after the war, Musota is surrounded by all that greenery. I realize, though, sitting here in our wretched little house and going back over those years, that it's not because I've forgotten how much we suffered in those days. I think that I was happiest in Musota because I was with you. I wonder if that is why I feel so fond of the place, although I don't think that's the main reason. It puzzles me that I should feel so attached to you, for—as Mother is always saying—you are so much a member of the Matani family. Unlike Mother, however, I do not have any strong feelings against the "family." Mother rebelled so much that you don't need to worry about me feeling the same way she did. Grandmother, I was reminded recently of the word "atavism." Because of Mother, I was able to be closer to you than any of my cousins. You yourself often said so. As you know, I'm studying at Tokyo Women's College, Mother's old college. I'm enrolled in the English Department like she was, but I think that my attitude must be very different from Mother's. After all, I'm working my way through college. Since Father's death, I have been receiving scholarships and working part-time to pay for my tuition and clothing. I don't mean to boast; it's considered quite common in Tokyo these days. I mention this only because Mother is full of remorse that even though she received a generous allowance from Grandfather and you, she rebelled against you. In my study of English literature, I came across the words of T. S. Eliot, who said that "tradition" should be positively discouraged. I cannot understand tradition as he describes it. According to Eliot, tradition negates all that preceded it and will be negated by all that follows. And yet I feel I know what he means when I think of the bond between you and me. The "family" has flowed from you to Mother and from Mother to me. Please don't laugh at me. One day I shall marry and have a daughter. It amuses me to imagine how my daughter will rebel against me and regard her grandmother with affection. And then, I shall think that, just as people lived in the distant past and will continue to exist in the years to come, however difficult the present may be for me, I must live for tomorrow. Now I know why I feel nostalgic about Wakayama. I could not have made this discovery or experienced this peace of mind and happiness if I had never been close to you. Hana wrote a reply to her granddaughter's letter using brush and ink. Instead of writing on beautiful Japanese paper, however, she wrote on ordinary stationery. Hana did not even attempt to explain the special bond between Hanako and herself. She merely described her daily routine, choosing characters so her message would fit on a postcard. Her letter was terse, but the sheer beauty of the calligraphy made Hanako feel that it was

brimming with news.

In the final scenes of the novel, Hanako graduates and finds a job with a publishing company and becomes a working woman. She saves to finance a trip to Wakayama. Her older brother is married and works in a business firm. Their mother Fumio barely manages on a widow’s pension of little value. Not only is she unable to buy things for her children but sometimes has to ask them for financial help. She recalls ironically that as a landowner’s daughter she did not have to work but felt sorry for those who did. The Occupation has ended, but this milepost goes unmentioned. There is no allusion to the ongoing Korean War, 1950-1953.

Fumio was over fifty years old. She had experienced hardship and the loss of her husband following Japan’s defeat and had suddenly aged. She had lost all her former vitality and had no desire to argue with her daughter, who candidly voiced her opinions.

At about this time [1955] they received word that Hana had suffered a stroke. Fumio, in response to the prompting of her sons, rushed to her mother’s side. However, she returned to Tokyo ten days later after learning that the stroke had been a mild one and that Hana would be all right. Fumio later confessed that she had been completely stunned by the ruins into which the Matani mansion had fallen in the ten years since the war. She had hurried back to Tokyo, because she could not bear to remain in the house any longer. Shortly after the death of his beautiful wife three years earlier, Seiichirō had resigned from the bank and was now living with Hana and Oichi. He was nearly sixty years old. He had stopped working, it seemed, in a vain attempt to uphold dignity of an old family.

"I felt as if I were looking at the ghostly ruins of an old house," said Fumio in the Wakayama dialect. Hanako listened to her mother, wondering if it were indeed painful to view the ruins of a house in which one had grown up.

When Hana had her second stroke, Fumio received word from both Utae and Tomokazu that this time her condition was critical. There was not enough money for both Fumio and Hanako to make the trip, so Fumio refused to go.

"I've already gone. You go this time, Hanako."

"All right, Mother. I've saved enough money for the trip."

It was the middle of summer, the hottest summer in ten years, and the city pavements broiled under the midday sun. How ironic it was that Hanako was escaping from this infernal heat because her grandmother had fallen critically ill! With mixed feelings of sadness at the approach of her grandmother's death and joy at returning to her place of birth, Hanako left Tokyo on the night train. She transferred to a Wakayama-bound train in Osaka and at noon the next day was walking along the narrow country road in Musota.

In Tokyo, more than ten years since Japan's surrender, modern buildings were appearing everywhere and the city changed face from one day to the next. But Musota appeared unchanged from the time Hanako had sought refuge there during the war.

Hanako is about to see her dying grandmother for the first time since the end of the war—thirteen years. She learns that Hana, age eighty-one, is partially paralyzed and sometimes delusional. The doctor has told the family that it is only a matter of time. The house is in much better condition than Hanako expects; unknown to her and the family, Hanako had sold valuables from the storehouse to an antique dealer and used the money for repairs and presents. Hanako kneels in a darkened room by the bedside of her grandmother:

"Hanako. How old are you now? Twenty-seven? You'll make little progress finding a husband on your own. Your mother believes that hers was a love match, but actually she was caught in a trap set by the adults around her. A woman should not become a career woman and remain unmarried."

"Well, I'm certainly not opposed to marriage."

"Your mother was twenty-seven when she had you. She made such a big fuss then, even in front of the nurses in hospital. She cried so much just giving birth to a tiny baby! All that lofty talk about freedom and her attacks on feudal institutions. But when she cried in labor, I knew she would never be a match for the women of the past who stoically bore their pain. I was so amused!"

Hana's face was sadly ravaged by time, but her voice was steady. Hanako, realizing that it would not do for Hana to talk too much, worriedly glanced back at Oichi. How could she silence her grandmother?

Hanako remains with her grandmother, listening to her recall the past and fret about her appearance. In wartime, her grandmother had never worn “pantaloons” [a reference to monpe], dressing always in a kimono with unshortened sleeves. To keep Hana quiet, the doctor advises reading to her. The family decides old favorites would be better than modern novels but no one can match her skill in classical Japanese. They settle on the historical tale, "Masukagami" ("The Clean Mirror"), which opens with the birth of Emperor Go-Toba in 1180. When it is Hanako’s turn to read, her grandmother corrects her. Later, as she combs her grandmother’s hair, the dying women confuses her with Fumio. The scene further indicates how little early postwar reforms had challenged Hana’s view of life and woman’s proper place or overcome her disappointment in her eldest son, a widower who had moved in with his mother and seemed not to care about the decline of the family...

"You've never combed my hair before. Fumio, you're already over fifty. How fortunate you are to have such a fine daughter!"

Hana again confused the two women and spoke to Hanako as though she were Fumio.

"I've always let you speak your mind and do as you pleased. Have I ever failed to send you the money you requested while you were in college and even after you married Eiji And yet how you ranted endlessly about independence and freedom! Hanako would laugh if I told her all about it. Both Kazuhiko and Hanako are such wonderful children. You must have been a good mother after all. One can never judge whether or not a woman has been successful in life without observing how her children turn out. Fumio, you've always rebelled against me, but I wanted you so much to remain near me. Seiichirō was unreliable. Tomokazu used the excuse that he was only the second son and let his wife run his life. How depressing it was to look after the Matani household all by myself! As a woman grows old, the thing she wants most to do is spend money extravagantly. It was the one thing I had not been able to do in recent years. That's why I've been so extravagant since I had my first stroke and realized that death was around the corner. You probably don't know about the lavish celebration I had after the mats were changed. Now, many people come to see me when they hear that I've had a stroke, because they know I'm very generous. You've always disliked the old-fashioned custom of exchanging presents, but it's really great fun."

Hana laughed a laugh that was both throaty and nasal.

"The family fortune began to dwindle from the time your father spent money as he pleased. Even if there had been no war and I had lived frugally, the family fortune would have been exhausted in Seiichirō's generation. The Matani family from which you ran away years ago has already become stuff for the history books. Take a look in the storehouse. All you'll find there are a few worthless objects.

Hana suddenly laughed.

"The storehouse is empty now, you know. Fumio, you often said that you couldn't stand seeing a woman so completely dependent upon her

husband and eldest son. You also said that being submissive was ridiculous. But I never thought of myself as being submissive. All I've done was to work as hard as I could. When your father was Speaker of the House, I did my best as the wife of the Speaker of the House. When your father became a member of parliament, I did my best as the wife of a member of parliament. And when Seiichirō entered Tokyo Imperial University, I did my best as the mother of a student attending Tokyo Imperial University. I really tried to do everything I could for Seiichirō until I realized that he was just a pale imitation of your father. There was nothing more I could do."

In the hectic days following Japan's surrender, Fumio had not had a moment to think about the Matani home. She had of course requested

money and had turned over her children to Hana, thus preserving on the surface the natural bond between mother and daughter. All the while, however, she had continued to rebel against her mother. Hana had therefore kept a lonely vigil over the dwindling family fortune. It was difficult for young Hanako to comprehend fully the intense loneliness her grandmother had experienced. As Hana continued her monologue, her teeth protruded from her mouth and a smile spread acros her wrinkled face.

"That's why I was so happy when our land was confiscated. I knew then that the Matani fortune could never be restored, and there was no

reason to feel apologetic toward our ancestors. Instead of feeling that all I had worked for was in vain, I felt elated and wanted to cry out your name.

I gave the excuse that it was for tax purposes and sold all the objects of value. Now that I didn't have to worry about what would happen after my death, a heavy burden was lifted from my shoulders and I was filled with great joy."

Once again Hana laughed.

Indulging a desire which she had held in check all her life, Han had begun to lead a life of limitless extravagance soon after suffering her first stroke. She had grown cheerful and had lavished money on herself just as money had once been spent freely on her husband, paying no attention to her widowed son.

Hanako continues to read to her grandmother and reaches the last chapters of the historical tale. As she looks into Hana's eyes:

A strange sensation swept over Hanako when she thought of Hana’s blood running through her own veins. The spirit of the Matani family still lived within her. There was indeed a powerful bond linking Toyono to Hana, Hana to Fumio, and Fumio to Hanako. Hanako felt that here grandmother’s heartbeats were pulsating in her own breast and no longer sought to decipher the cryptic text she was reading aloud. Had the Buddhist priests—who for thousands of years had chanted the sutras before the statue of Buddha, the object of worship of hundreds of thousands of men and women—experienced a similar emotion? No longer did Hanako feel that she was reading the text as a devoted granddaughter. Believing that this was what was required of her in order to inherit from Hana the vitality of the countless women who had lived and died in the family, she read as one possessed, not realizing that she had raised her voice.

And so Hana’s life ends even as Fumio, in a change of heart, makes her way to Musota. Hanako prepares to return to Tokyo after a prolonged absence. Before leaving Wakayama City, she enters the gate of the city park, climbs up to the lookout platform of Wakayama Castle and looks through a large telescope.

Below her lay Wakayama, which had been speedily reconstructed after the war. Looking up, she saw the blue sky. Finally getting the instrument under control, she focused the lens on Musota and could even make out the Matani mansion in Agenogaito. It was not much more than a dot but was still clearly visible.

On this side of Musota, the River Ki appeared smooth and tranquil, giving the impression its waters were perfectly still. The river was a lovely blend of jade green and celadon. Hanako slowly turned the telescope downriver and was impressed that the color was the same. The ugly smokestacks close to the mouth of the river loomed into her scope of vision. The huge factory of Sumitomo Chemicals, funded by interests in Osaka, spread out slightly to the north of the river's mouth. Keisaku's dream had been to develop both waterworks and agriculture so that Wakayama would not be ruined by outsiders. But the war had destroyed his dream. Disappointed to have the magnificent view marred by an ugly factory, Hanako stepped back from the telescope. The forest of smokestacks rapidly receded into the distance and

beyond them lay the ocean.

Hanako heaved a sigh of relief and in that instant the telescope clicked: the lens cap had automatically closed. She moved away from the telescope and gazed for a time at the vast, mysterious ocean whose color changed as the sunlight played upon the waves.

......................... Reference:Ariyoshi, Sawako. The River Ku. Trans. Mildred Tahara. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1980; excerpts, 201-243.

|