JAPANíS 1ST WOMAN JUDGE THINKS SEX NO BAR TO JOB

by Shiraishi Tsugi

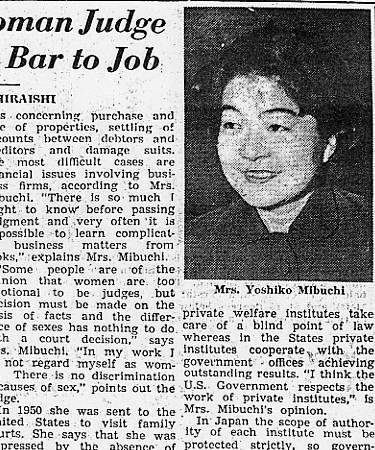

Mrs. Mibuchi Yoshiko, Japanís first woman judge. Mrs. Mibuchi Yoshiko was one of the three first women lawyers in Japan and after the war became the first full-fledged woman judge. At present she is serving at the Tokyo District Court.

In prewar days women who wished to become lawyers enrolled either at Meiji or Waseda universities which alone among the higher institutions accepted women students. Following the graduation they had to pass a judicial examination which qualified both men and women to execute laws. However, the Government decreed that judges and procurators must be male. This discriminatory regulation was abrogated after the war giving equal opportunities for employment to women.

Mrs. Mibuchi came out fourth among 242 contestants in the judicial examination in 1937 and began teaching at Meiji University and later worked at the Justice Ministry. In 1948 she was appointed as assistant judge and three years later became a fully qualified judge attached to the Nagoya District Court. Since 1956 she has been serving at the Tokyo District Court as the only female judge.

Mrs. Mibuchi thinks that the work of judges suits women as well as men though the duty of procurators may be too strenuous for women unless they are the "dry" (tough) kind. "It is hard for women to rush to the scene of murder at midnight," says Mrs. Mibuchi.

This female judge handles civil cases which include, matters concerning purchase and sale of properties, settling of accounts between debtors and creditors and damage suits. The most difficult cases are financial issues involving business firms, according to Mrs. Mibuchi. "There is so much I ought to know before passing judgment and very often it is impossible to learn complicated business matters from books," explains Mrs. Mibuchi.

"Some people are of the opinion that women are, too emotional to be judges, but decision must be made on the basis of facts and the difference of sexes has nothing to do with a court decision," says Mrs. Mibuchi; "In my work I do not regard myself as woman. There is no discrimination because of sex," points out the judge.

In 1950 she was sent to the United States to visit family courts. She says that she was impressed by the absence of sectionalism among government judicial offices. Further explaining the point she states that in Japan a juvenile delinquent is first taken to a child consultation center, then to the family court and finally to the police. The child is asked the same questions three times, thus going through an unpleasant procedure repeatedly whereas in the States details about an arrested delinquent youth is recorded on a card which is used by all the judicial institutes, both public and private.

Another difference between the Japanese system and the American system is that in Japan private welfare institutes take care of blind point of law whereas in the States private institutes cooperate with the government offices achieving outstanding results. "I think the U.S. Government respects the work of private institutes," is Mrs. Mibuchiís opinion.

In Japan the scope of authority of each institute must be protected strictly, so government officials are always afraid to take any steps which might be criticized as an infringement on the othersí authority. I think that in the States the judicial authorities regard laws as a means to protect human rights, notes Mrs. Mibuchi.

The wife of Kentaro Mibuchi who is with the Supreme Court and mother of four children, Mrs. Mibuchi in her middle 40s hardly looks like a judge as she speaks softly with warmth and humor about her work.

She is so busy that she has hardly time to look after the family, but she feels that all her grownup children can take care of themselves.

Site Ed: According to the Nippon Times, the first woman judge was appointed in May 1949 (see image, "First Woman Judge," Ishiwata Mitsuko).

.........................

Reference

Shiraishi, Tsugi. "Japanís 1st Woman Judge Thinks Sex No Bar to Job." The Japan Times, April 21, 1959.

|