TOMIYAMA TAEKO

An Artist’s Life and Work

by Rebecca Jennison

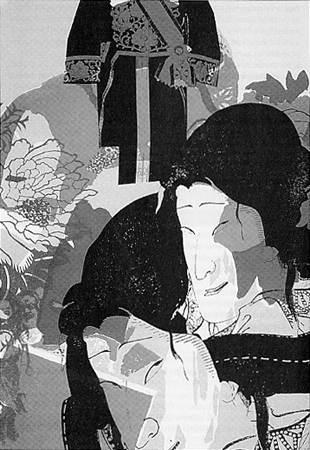

"Sold off to the Continent." Serigraph 54 cm x 41 cm. From: Jennison, 100. Rebecca Jennison (RJ): I recall that we first met in Kyoto in the late 1970s at an exhibit of your work on Kim Chi Ha. Since then I have continued to learn from and be inspired by your work. Could you tell me a little about the experiences that have shaped your career as an artist?

Tomiyama Taeko (TT): I think those formative experiences can be found in the time and place where an artist’s first memories are rooted. For me, they are rooted on the eve of the Second World War in Harbin, where I was a schoolgirl. The Kanto Imperial Army had already set up a colonial, military regime, and Special Unit 731 was located just outside the city. When I think back, it was growing up in that time and that place—those are the two things that first began to shape me as an artist. You could say they were pivotal factors in my becoming a "political" artist. I hope people will look at my work and understand it as a statement of what one artist in Asia is thinking, especially one working in a country like Japan, which is now a sort of colony of the United States. I also hope they will start to imagine what it has been like for me as a woman artist working in the midst of a male-dominated art world.

Another aspect of my life is the way that living and working in a multiethnic community has been important to me. That is what I prefer. From the time I was a schoolgirl in Harbin, I have lived in multiethnic communities. To think about and work on things together with others outside of the Japanese context has always been important to me. In the 1960s, I traveled to Latin America and met many different people... and also to Korea and many other places. Among other things, this has taught me that art cannot be defined as belonging to any one country. As a result, I have been able to build many alliances across borders. If I had just stayed in Japan, I would have given up long ago. But leaving Japan and meeting like-minded people has been vitally important to me. I continue working together with people I have met abroad over the years. One common theme that has brought me together with others is the critique of colonialism. I have been able to think about this topic especially because of the encounters I have had outside of Japan.

RJ: When did you first know that you wanted to become an artist? What obstacles have you encountered?

TT: When I think back to my childhood, I recall feeling that I would first have to protect myself from the family system [kazokushiugi]. When I first knew that I wanted to become an artist, in my teens, I could see that I would first have to fight against my own family’s expectations of me. My parents were more liberal than many, but when I told them that I wanted to become an artist—this was a time when new movements in Europe such as surrealism and cubism were quite influential—my father said, "If you’re going to paint pictures like that, I’m not going to send you to art school. You have to master basic, academic skills first." He didn’t understand me. Nor did my mother who wanted me to have a skill, to be a teacher or something, so that I would have some way to support myself if I wasn’t happy in marriage. She wanted me to be able to eat; not to be an artist. Their notion of "artist" for a young woman was as a kind of hobby that she might continue to pursue while in a bourgeois marriage.

In my school, there were many Koreans and Chinese. I saw them as my allies and didn’t like what I saw of the Japanese. The military—I thought they were awful, that I was not like them. I loved Pearl Buck and read all of her works. At about fifteen, I started ordering art books from Tokyo. When I didn’t understand some of the terms, I’d order a dictionary too. But I had to scrounge for the money because my parents wouldn’t give any to me.

RJ: So after Girl’s School, you returned to study art in Tokyo, is that right?

TT: I went to Tokyo in 1938 to study at the Women’s Art College in Tokyo, but it wasn’t long before I rebelled against the academic system there. I had learned about the Bauhaus movement and was more interested in pursuing the kind of work being done there than in doing academic exercises at the college. So they expelled me. I remember hating the war because it was destroying my dream to become an artist. I hated it and wanted it to end soon.

When the war did finally end, I began to question what it had been all about. I started reading books about what had happened, and I remember starting to ask questions about colonization, too. In some books it said that the Japanese had come to Manchuria in order to "protect the Japanese." I recall feeling so angry when I read things like this. My parents and school friends were telling me about how the colonial administrators who stayed in Manchuria after all the high officials had left were giving people arsenic, telling them it would be better to die. I wondered what sort of country would tell its own people to die, when the rulers were just thinking of themselves, and when they were saying they were there to protect the people.

It all made me think. What is the State? What does it do? After the war I felt so angry at the older generation. Then we started to hear news of what had happened in the Holocaust in Europe, about atrocities committed by the Japanese military, and about the bomb dropped by the Americans on Hiroshima. I was still studying to be an artist, and was learning that the artists who were supposed to be our models had been to France where they learned to paint works in French styles. They’d come back to Japan, become well-known, and had been able to sell their works. The art world in Japan was very European-centered, I felt, just following the trends in modern Western art. We also began to find out that many Japanese artists collaborated in the war effort. But it was taboo to talk about that. I knew I hated the idea of just copying that sort of work. I knew I would have to do something different.

Everything was changing so quickly. When we heard the news that the revolution in China had succeeded, I remember feeling amazed by the idea that such change could occur. I had seen it—the real oppression and poverty in China. Now it seemed that there could be something new. I read everything I could by Edgar Snow and Agnes Smedley. It was then that I first started learning about the poverty, suffering, and struggles of miners. In that sense, from early on, "the political" was part of reality for me.

RJ: So as an artist, what you wanted to express was your sense of that "reality."

TT: For me, that reality was the sense of Asia changing rapidly... and my astonishment at seeing those changes along with the disintegration of Eurocentrism. That was an important starting point for me as an artist.

RJ: How do you feel about being described as a "political artist." Is that a term you accept?

TT: When you think of the situation of the art world in Japan then—and now too—you can see how completely different the direction I took was. But from another perspective, we can say that the "fine art" world itself is "political." From my point of view—I have to ask, which one is political? Yes, in Japan I am labeled a "political artist," but when you think about it, you have to ask, which is which.

RJ: Hagiwara writes about how the artist’s organizations in the postwar era were structured in a way that reflected the larger, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)-centered political system. You have explained that you joined the "Jiyu" (Liberal) Art Association ["liberal" in this sense meaning "the free pursuit of genuine art"], which was censored and suppressed until the end of the war. Can you say something about this early period in your career and what led you to leave Tokyo to go and work in the Chikuhō region in Kyūshū?

TT: For me, the subject of the mines in Kyūshū touches on the theme of "being underground" in many senses of the word. Taking up the theme of the mines, and miners’ struggles, I couldn’t help but become "political." In the postwar period, the "Joryu Geijutsuka Kyokai" (Association of Female-school Artists) was formed. Women artists were being treated badly by male artists in the male-dominated art associations and so Migishi Setsuko and others gathered together and formed their own group. They asked me to join, but I didn’t want to. I felt uncomfortable with the notion of a "female-school" —after all, there is no such thing as a "male-school," is there? I didn’t like thinking in terms of "male" and "female" artists...so I joined the Jiyu" (Liberal) Art Association. I was one of the first members. It was a little after that when I started working on the theme of the mines. Many male artists I knew were also very critical. A few were receptive toward me, but most said, "What can a woman understand about the mines? Women should be more “womanly.”

With the shift from coal to oil, it became difficult for the miners to continue their struggle; many of the smaller mines were forced to shut down and many workers left. I decided to follow some of the workers who were emigrating to Latin America. Some went to Bolivia, others to Brazil, mostly as agricultural workers. When I arrived, I found that people were very interested in my work. The newspaper did a big article about me. In Japan I had been treated like an outsider ... but in Brazil, they took me more seriously. Brazilian intellectuals took me in and encouraged me. I met a woman, an artist of my generation. She was Jewish and had escaped from the Nazis in Germany when she was sixteen. Her name was Eva Liblich Fernandez. Her husband—a leader in the Brazilian Communist Party—had gone as the Brazilian representative to China for the inauguration of Mao Zedong’s new government. They knew a lot about the situation in China. I soon became good friends with Eva, and studied Spanish. Their home was a gathering place for Brazilian intellectuals then, and I became a part of their circle.

RJ: How long did you stay there?

TT: I stayed there for about a year. When I was getting ready to leave, they asked me to return via Cuba. Brazilians weren’t allowed to go to Cuba, and since Cuba was so important for them, they asked me to go instead. There was a poet named Nicolas Guillen living there; he had joined the antifascist struggle in Spain and had lived in Brazil for awhile. Eva said that she would write a letter of introduction to him for me. It was all quite something, just before the Cuban missile crisis. I was warned it would be dangerous, but I decided to go anyway. So I went and got a ticket to Havana on Pan American, the only airline flying to Cuba at that time (via Miami). When I boarded the plane after an overnight in Miami, I realized I was the only passenger. The plane was being sent to pick up evacuees. The return flight was to be full. So I was the only passenger and the flight crew was sitting at the other end of the plane; they brought me coffee and cookies... and then we arrived in Havana.

I took the letter of introduction from Eva and met the poet, Nicolis Guillen, who told me I should meet some artists. He took me to meet the head of the Havana Art College who, along with a Black woman artist, showed me around every day. This was in 1962 when the U.S. blockade was in effect, so everyone was very tense, wondering when the war would start. What a memorable experience. When it was time to leave, I found that I was on the last plane out. Everyone was saying there’s going to be a war, so "evacuees" from Cuba. I was able to spend a little time in Mexico and was fortunate to be able to see something of the artistic renaissance there. My eyes were opened by the mural art of Rivera, Orozco, and others. I felt that I was witnessing a third world country choosing a different path from that of the West. I was really moved by this. I thought, when I get back to Japan, even if a vital movement isn’t possible, here I have seen a way to begin looking for a different path. Those were my thoughts as I left by ship from California to come back to Japan.

RJ: What did you do when you returned to Japan?

TT: I returned late in 1962. After a couple of years, I traveled to Afghanistan, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and other countries in the Middle East. In South America, I had seen the vestiges of Spanish colonization and the more recent impact of immigration and U.S. domination. I wanted to learn about the colonization of Central and Western Asia. I ended up being there at the time of the Mideast war in 1967.

When I returned to Japan, I felt overwhelmed by all that I had seen and didn’t know what to do. I decided to stop painting for a while—I was again rejecting the options that the "art world" seemed to offer—and threw myself into the student movement. When I was able to step back and look around, I immediately saw the military dictatorship in South Korea and I decided to go there. That’s when I learned about Kim Chi Ha, the poet. The question of "colonization" I had been thinking about was right there, so close. I decided I would start to do some work related to the theme of the military regime. Now, when I think back, I can see that all of these things are somehow linked, connected.

RJ: So that’s when you began to do lithographs working with Kim Chi Ha’s poems. Can you say a little more about how you came to do collaborative projects with other artists? How have you come to see the role of the artist?

TT: My work was to be shown as part of a television documentary on Kim Chi Ha—part of growing international efforts in support of the poet. But the broadcast was canceled—rather, censored. They said it was because it would "harm international friendship." I then decided to remake the program, creating a series of slides. That’s when I met the musician and composer, Takahashi Yuji. He had been working in New York with John Cage, and was performing in Japan and Europe. He was disillusioned with the professional music world and had started doing alternative projects in 1975, when he formed the Suigyū Gakudan. In 1976 we started to collaborate on multimedia slide presentations using my art works and his music. I also started a Hidane Kŋbŋ, a studio for the production of these multimedia works.

I first took the work to America. In New York, I met poets who were working on Korean issues. There was a group of them there. One of the leaders of the group, who had gone on a hunger strike on behalf of Kim Chi Ha was Muriel Ruikeyser. She was the representative of the PEN Club in the United States at the time. I had an exhibit at the Interchurch Center in New York City. At that time, almost no one knew about Kim Chi Ha.

Since I had been in Latin America and knew Neruda’s poems, we presented Neruda’s poems with Kim’s. People from many different activist groups came together—Chicano groups, human rights groups, Amnesty feminists—many different people. With support from those people, and Christian groups active in liberation theology, the movement got going. I was there for three months. When I left, they asked me to leave my prints behind. On my return, I went through Chicago and Berkeley and gave lectures. Many people made donations and we all worked together. It was an exciting time to be there. There were so many political and cultural movements coming together. And everyone was working so hard.

Looking back, it was critically important for me, going to America at a time when all of that was happening. I did not really have a clear vision of my own yet then. I only had the feeling that we had to come together to create something. That was a very important experience for me as an artist.

RJ: In the early 1980s, you took your work to Berlin. What did you do there?

TT: I showed my series on the people’s uprising in Kwangju. Most of the Japanese in Berlin around that time were of the elite; many had gone to study at the Free University there. At the same time, there were many Korean immigrants, working as nurses. Some had formed the Korean Women’s Group in 1976. They tended to view the Japanese with suspicion, but they hadn’t really spoken to any of them. They came to my exhibit and began to speak to one other for the first time. Some of them then started to work together to help political prisoners in Korea. I think that was when the Onna no Kai (Women’s Group) was formed too.

RJ: We have seen a number of the themes that have emerged in your work. Do you view them as having developed in a straight line of progression? Or do you see yourself changing in significant ways?

TT: I certainly see them as interconnected, but I have also changed. In the 1980s, I began to think more about my position and perspective as a woman artist. I think that is reflected in the series “A Memory of the Sea," which treats the theme of the silenced voices of Korean "military comfort women." I have also tried to view things more and more from the perspective of Asia. So even if I continue to pursue older themes, I am looking at them from a slightly different angle.

RJ: What about the development of your work since the 1995 Tama Art University exhibit “Silenced by History”? In works shown in that exhibit commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war, you began using the image of the fox. There were images of foxes in uniform celebrating the foundation of the Manchukuo, and at a wedding ceremony for a soldier about to go off to war. Why did you use this image? How has it developed since then?

TT: Forty years after the end of the war, I began to feel that I could more directly address the question of war responsibility in my work. I went back to Harbin in 1991, just after the collapse of the former Soviet Union. I was looking through materials and wondering what images I might use in my work to say something about war responsibility. Then I saw Kitsune (Foxes), Takahashi Yuji’s opera or musical performance that was based on a book by Yamamoto Hiroko, a medieval scholar who explored the connection between the fox spirit in Shintoism and the structure of authority, particularly in relation to the emperor system. When I saw the performance, I felt immediately drawn to the image of the fox. It’s so familiar—there are three fox shrines [inari] right in my neighborhood in Tokyo. That’s when I thought I’d try using this image to tell the tale of Harbin and Japan’s colonization of Manchuria.

The setting for the series is Manchuria in the 1930s, the very era when I was a schoolgirl in Harbin. It dawned on me that from the ceremony commemorating the foundation of Manchukuo—the "new paradise where five races live in harmony" —that whole era itself had been in the grip of fox-possession. The works I painted using this image became the "Requiem to the Twentieth Century: Harbin Series," which I exhibited in Tokyo at the Tama University Museum of Art and later at the Tong A Gallery in Seoul.

RJ: You have continued to work on that series. The fox appears everywhere in your more recent work as well.

TT: After the "Requiem" exhibit, I began asking myself where those foxes had gone? And then I began to see them—here, all around us. It was as if after the war, they had cleverly transformed themselves once again. They are tricky, you see. They used their trickery to hide the past in a hole. Now they’re back, living in the shadows of the chrysanthemum, which is still a symbol of the emperor system. I wanted to use the image of the cherry blossom because the "ephemeral cherry blossom" has been used so often to aestheticize death and the war. As I see it, the foxes and their tricks have helped those in power to deceive people. First, they say they want to fight a war, then they say they like peace. They give arsenic to the people saying they should die rather than live under the rule of the enemy; then they shake hands with MacArthur and go on doing their tricks.

As an artist, I must become a trickster too—and use my craft to expose their deception. As I worked on this series, I began to imagine that with the passing of time, new winds and currents were bringing boats filled with the memories that those foxes were supposed to have hidden. The boats began pouring in from other Asian countries.

RJ: The exhibit in Setagayaku, "The Foxes and the Mines," also includes works that take us back to your beginnings as an artist: the theme of the mines in the Chikuhō region in Kyūsh၍. Can you tell me a little about this part of the exhibit?

TT: I started on my path as an artist in the 1950s by making the mines the central theme of my work. Even though I left the region and traveled many places, this theme kept coming up. In the 1970s, it reappeared when I was working with Kim Chi Ha’s poems. In Chikuhō, the memory of Koreans conscripted during the war to work in the mines was buried everywhere. In 1984, the series of works I did on the mines, was produced in collaboration with others as the film Hajike, Hōsenka (Pop out balsam seed), dedicated to Korean miners who worked and died in the mines. That was in 1984 ... and I thought that that was the end of my work on the mines. But now, in this exhibit, I have collaborated with photographer Motohashi Seiichi, using photographs and lithographs to make new collages that address this topic once again. This time, we tried to do so from the perspective of the end of the twentieth century. To look at this again, after forty years, knowing that the landscape I first saw there is now gone, I found I still wanted to tell of the memories of those who were burned alive there, those who were turned to ash.

RJ: In the catalog for this exhibit, you write that the work embodies "what you want to say to the twentieth century." Where do you hope to go as we move into the twenty-first century?

TT: The situation in Asia is continuing to change rapidly. I feel there is a new wave of interesting cultural work that will come out of Asia. In my own work, I am beginning a project that will again be a collaboration, this time with the Kwangju artist Hong Sung Dam. I am continuing to explore the experience of the colonization of Manchuria. Our aim is to collaborate, from both perspectives—that of the colonizer and of the colonized—to continue reexamining that history.

What am I aiming to do? I want to continue to try and give expression to everything that is etched in my heart and memory. A half a century has passed since the end the war. That’s a good period of time. Now is a good time to really look back and see it ... and from there, to try and create something new in the twenty-first century.

.........................

Reference

Jennison, Rebecca. "Tomiyama Taeko: An Artist's Life and Work," Critical Asian Studies, 33:1 (2001), 101-119. Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

|