SHADOWS FROM A DISTANT SCENE

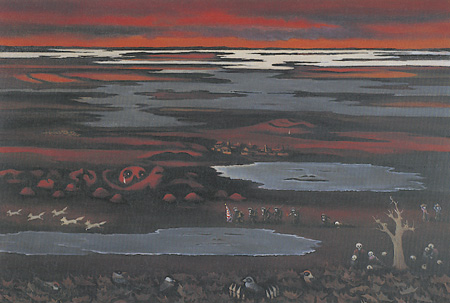

by Tomiyama Taeko

In a colony pleasure and suffering coexist side by side.

In the zone of pleasure live the colons and their collaborators. On the suffering side live the people of the country itself. The colons live in perpetual fear of uprisings and resistance from the 'natives.'

I spent my formative years in Harbin and Dairen in the former Japanese colony of Manchuria. What we lived in fear of was to be attacked by the guerrillas, whom we called 'bandits.' I remember how we primary and junior high school students would stand on the station platform waving little 'Rising Sun' flags to send off the Japanese soldiers, champions of justice, who were going off on punitive expeditions to suppress the 'bandits.'

It was just as the Sino-Japanese War of the 1930s was expanding into the Asia-Pacific War that I finished my primary school education and started in as an art student.

When I left Harbin and went to Tokyo to go to art school, everything was tinted with the colors of militarism. The art that I felt closest to at the time was the surrealism of the 1930s.

Manchukuo at sunset, 1945 Max Ernst's nocturnal forest wrapped in uncertainty. Salvador Dali's unreality, vibrating a sense of danger from the ruin that lay over the horizon, or the avant-garde art of Europe on the eve of the Second World War that looked like reality, fading into the horizon, scorching the sky with reds as it went like the predark glow of sunset. Then the darkness.

I would try to make out what was there, rub my eyes wanting to see, strain my ears, only to hear the sound, like a ground swell, of marching boots. The sound grew louder and louder and my youth was swallowed up in the murky depths of war. My art school friend went off to war, trying to resign himself with, "Oh well, I've had twenty five years." A collection of the works of the art students who died during the war was published later. Most of the male students had died on the battlefield. Mine is the war generation.

In the midst of the wretchedness of war and the hunger that dominated our lives after the war, my artistic sense began to change. Wandering over the burnt-out wasteland, scrounging for food, I recalled the pathetic scenes of Chinese that I had witnessed as a child in Manchuria.

In 1949 the Chinese revolution triumphed. The people whom we Japanese had called 'bandits' and 'reds' entered Tienanmen Square to the cheers of the crowds. Then it became clear what acts of barbarity the Japanese army had perpetrated on the continent of China under the slogan "Burn, rob, and kill all."

* * *

Should the artist be a passive observer of the times? The postwar period for me began with the hard reflection that I had let myself be blown along on the winds of the time.

From the 1950s to the 1960s I painted pictures on the theme of coal mines.

The coal mines that I was particularly fond of were those in the Chikuho coal basin in northern Kyushu. The huge coal waste heaps that towered over the ramshackle miners' housing, exposed to the winds and washed by the rain, were engraved with deep wrinkles like the face of an old person.

The coal mines that had grown alternately fat and lean during a century of wars had crushed the bones of the impoverished miners and swallowed up the lives of Koreans and other oppressed people.

People did not necessarily find my depictions of the sooty coal mines beautiful; in fact many said they suggested scenes of hell. But for me the coal mines, soaked with the sweat of generations of laborers, were beautiful places. But this being the world of art, not documentary literature or film, the nearly ten years I spent on this theme went by in uncertainty and trial and error.

Let's go to Japan! The shift from coal to petroleum as the main source of energy was beginning at this time, the struggle of the Miike colliery of Mitsui Mining Co. had ended in defeat, and a number of the miners who lost their jobs emigrated to Brazil and Bolivia. A year-long trip through Latin America in pursuit of these miners was my first encounter with the Third World.

On the way home I stopped in Mexico and was greatly impressed by the murals that I saw there. I began to realize that I had been tied to a Western concept of art and to the tableau as the form of my expression. But did the conditions exist in Japan, I wondered, for painting on walls?

In the fall of 1970, the year of Expo in Osaka, touted as a celebration of Japan's postwar high economic growth, I decided to go to Seoul. On the way I recalled a scene that I had witnessed while traveling between Harbin and Tokyo during the war. When the ferry from Shimonoseki had arrived in Pusan Port, I had watched with apprehension as the security police scanned the passengers disembarking and then arrested and led off several of the Koreans.

I bought a bunch of green grapes in Pusan, and as I ate the grapes, which were as large as Muscats, looked at the view out of the train window. After the war I had read a poem entitled "Green Grapes" by Lee Yuksa that had appeared in an anthology of Korean poetry.

July in my village

Green grapes heavy on the vine

The old legends of my village hanging down

The distant sky dreamily reflected

in the rounded fruit

(Lee Yuksa, "Green Grapes")

These lines, superimposed on the scenes of the rugged hills and peaceful villages I saw from the train, have remained with me as my image of Korea. The poet, Lee Yuksa, died in 1944 at the age of 39 in Beijing from torture at the hands of Japanese security police. Being Japanese, and knowing all of this, I had hesitated to set foot on the soil of the Korean peninsula. But twenty five years after the war I wanted to see those scenes once again.

The war had been over for a quarter century in Japan, but the devastation of the Korean War of the 1950s had left deep scars everywhere. After Japanese colonial rule had come the Korea War, the 'proxy' war between the US and the Soviet Union, splitting Korea into North and South and freezing the Cold War into its soil.

A country of night, soldiers always on guard. And before I knew it I was painting the roads of this night.

In 1971 I had an opportunity to visit Soh Sun, a Korean student from Japan. It was at the Sodaemon Prison in Seoul, and he bore the fresh scars of his attempt to immolate himself.

At the sight of this young man, ears and lips melted and face covered with keloid, the recently published poem of Kim Chiha, "Yellow Earth" engraved itself anew in my heart.

Following the vivid blood,

blood on the yellow road,

I am going, Father, where you died.

Now it's pitch dark, only the sun scorches,

Hands are barbed-wired.

The hot sun burns sweat and tears

and rice-paddies

Under the bayonets through the summer heat.

I am going, Father, where you died.

(Kim Chiha, "Yellow Earth")

Guided by the image of this poem I began to draw pictures to appeal for the release of political prisoners. I felt that black and white lithograph provided a better medium of expression for the subject matter than oil.

Not long afterwards Kim Chiha was arrested. I drew pictures on this theme, and another ten years passed. Political prisoners in South Korean prisons did not exactly strike Japanese as aesthetically beautiful subjects. But I believe that the message which Kim Chiha was sending from his dark prison was somehow filled with light.

The lines from Isaiah, "The people that walked in darkness has seen a great light, to those who sit in the place of the shadow of death, a light has come," had a reality for me that pursued me in my work.

Working on a theme related to South Korea brought me up against a wall of prejudice in the art world of Japan.

The 'Oriental Art' typified by Lee Dynasty ceramics or calligraphy might be alright, but in a Western-oriented art world, modern Asia was not a subject for art. It was next to impossible to find galleries that would exhibit my pictures, aimed as they were at calling back to mind a war that everyone wanted to forget, a colonial past that no one wanted to deal with.

In order to bring the message of the imprisoned Kim Chiha, who had been sentenced to death, to as many people as possible, I lit on the idea of using slides. With the cooperation of artists in several fields, works incorporating poetry, music and pictures were produced in the new media of slides. These I showed at all kinds of gatherings around the country.

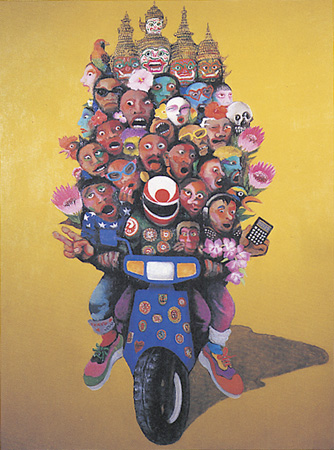

The 1970s were the years when the world became aware of the existence of Third World poets and artists imprisoned for their political beliefs and the years that produced a worldwide movement for their release. My slide creations were sent to Amnesty International, to progressive religious groups, and to grassroots movements in various countries. In a compact medium, they conveyed the voices of the imprisoned beyond the prison walls and stimulated the creation of a new, people's 'culture of resistance' different from the culture of capitalism.

And in the course of painting South Korean subjects I realized the deep scars that Japanese colonial rule had left on the lives of Korean people.

For the one who is trodden on there is naturally pain. But for the one who does the treading too, some painful sensation is normally felt on the foot at the time. But for the Japanese, who trod on the Koreans with thick army boots, evidently no pain was felt.

Coal mine, Chikuho. The bitter history of the Koreans was engraved in the coal mines that had been the theme of my work in the 1950s. Bones in a plastic bag left in the corner of a temple with no one to claim them thirty years after the war. I wanted to call up the voices of anger and lonely isolation of those dead who were buried in obscurity, nameless, recorded in the temple records as simply 'unidentified Korean.' I could, as an artist, at least bring together vestiges of the lives of these Koreans who were being forgotten in death. Then, with the cooperation of friends with expertise in various fields, the film "Hajike hosenka, waga Chikuho waga Chosen" [Pop Out, Balsam Seeds!— my Chikuho, my Korea] (see plates on pp.30-40) was completed.

* * *

In the course of researching the forced relocation of Koreans to Japan, I became aware of the existence during the war of Korean 'comfort women.' I put this theme into a series of pictures, held performances, exhibitions and a slide show, "Umi no kioku"[A Memory of theSea] (see plates on pp.41-48). The 1980s came to an end.

* * *

In 1991, watching the news of the collapse of the Soviet Union, I recalled the Russian refugees from the Russian revolution whom I had seen in Harbin.

In our colonial education in Harbin we had the 'red threat' drummed into us. Japan had to protect 'Manchukuo' from the Soviet Union, the red Soviet Union, wrapped in a veil of mystery, violence and fear, a land of terrifying secret police who carried out one Stalinist purge after the other. And Harbin came to be known as an anti-Communist bulwark holding back the spread of red influence.

The white Russians who had fled from that terrifying red country had probably led affluent lives in the old days. The Japanese looked at these refugees with the eyes of sentimentality, with expressions of fawning admiration for Western culture. The aspiring artist that I was might have sketched the street-corner 'accordion players or other folk that appeared in the pictures of a Chagall but would never have made the lives of the poor Chinese the subjects of my paintings.

In the winter of 1938 the newspapers were full of the dramatic escape from Sakhalin into the Soviet Union of the actor Okada Yoshiko and her lover Sugimoto Ryokichi. Having been told that it was a land of Stalin's purges and the fearful secret police, I wondered why they had fled there. I wanted to know more about the Soviet Union, the country that she, the artist Okada Yoshiko, had chosen.

I began to ask myself: just what is the Soviet revolution? Not long after I came to Tokyo and started in as an art student I learned that many of the artists whom I looked up to had, as they put it, "committed their youths" to the Soviet revolution. Was that country a hell or a heaven? I was to ponder this question for many years to come. Much later I learned of Russian avant-garde art and of the world that had fascinated artists of the 1920s.

That was the emergence of public art, an art that rejected the authorities of art and that sought to exist together with the new civil society, but the artistic sense of the people did not keep up with it.

It takes a long time for history to reveal itself. Yes, I would go to Harbin. I would learn what it was that I had seen with the eyes of my youth.

* * *

In late March 1992 I looked out upon scenes of early spring from the window of the old 'Manchurian Railway' train heading for Harbin. It was not the wild prairie of the old days, but had changed to a rural landscape of carefully cultivated fields and windbreak forests. But beneath this vast land lay many sad lives, now only bones. Each of those lives, holding more suffering than could ever be told, was now a clod of earth. I would draw a requiem for these innocent people.

What I had seen before the shadow cast by the Russian revolution, the struggle for Korean independence, the days of the pain of the Chinese revolu tion, the establishment and the collapse of 'Manchukuo', the invasion by Japan and its defeat-the turbulent history of East Asia was deeply engraved in Harbin. I thought of the lives of the people that I had met there-the Chinese, the Koreans, the white Russians, the Jews, and the Kwantung Army.

But the only ones who survived unscathed were the ones who had started the war.

In 1945 when Unit 731 (the Ishii Unit) got word before the defeat that Japan would unconditionally surrender, it liquidated all of the people interned for use as live guinea pigs in its experiments and blew up all the buildings to destroy the evidence. A record of the families of Unit 731 members can be found in the class book of the Harbin Girls High School alumni. It says that unit members and their families who were at the Ishii Unit garrison in Pingfang evacuated via Korea straight away on the 11 th and 12th of August in a special train.

Japanese settlers in the outlying areas only heard about the surrender after August 20. When they arrived in Harbin after making their way, starving, across the plains, they were completely exhausted, and the primary school for Japanese in the city was filled with the corpses of those who subsequently died. Many of the war orphans who have come to Japan in recent years to locate their relatives were separated from their families in Harbin.

The train was approaching Harbin Station. It was from here that I had left for Tokyo to enter art school and become an artist.

Now a half-century later I would stand in Harbin Station in early spring. To draw Harbin-shadows from a distant scene had pursued me down to the present.

[Translated by Jean Inglis and Muto Ichiyol]

.........................

Reference

Silenced by History Organizing Committee. Silenced by History: Tomiyama Taeko's Work. Tokyo: GendaiKikakushitsu, 1995; 59-61.

|