AYANO CHIBA: Weaver and Dyer

by Barbara Adachi

Chiba in her early 80s. "Mukashi no mama., mukashi no mama" ("Just as in the old days, just as in the old days"). Ayano Chiba slapped her kimonoed knees for emphasis as she nodded and smiled. The bright-eyed old lady sat in her small matted room with her legs tucked neatly under her diminutive frame.

"The Nara period? Well, I don't know much about all that although I suppose there must be some books in Kyoto that tell about all this weaving and dyeing," she s ai d in the strong dialect of northern Honshu. "All I know is that I've been doing it for a long time and my family had done it for a long time and lots of people around here have done it for a long time. But I'm the only one left now. Guess there's no one foolish enough to take up this troublesome work these days. And it is lots of trouble you know, lots of trouble. But I've done it all my life, more or less, so I might as well keep at it. Reckon I couldn't just take it up at this age if I hadn't already been at it for years and years!"

Mrs. Chiba's career in dyeing covers fifty years. She did not start working with indigo on her own until she was thirty-four, having watched her parents and grandparents prepare and use the dye when she was a child. Her days at the spinning wheel and the loom started when she was a girl of fourteen. "Why, of course I started spinning when I was young, and I worked at the loom too. We were a farming family, but there was always a bit of time to spin and weave. I used to weave asa (hemp), cotton, and even silk. I wove many a bolt of silk material when I was a young girl, I'll tell you, many a bolt. I still weave sill, now and then. Not cotton, though, and wool only once in a great while. I stick to asa."

The hemp that Mrs. Chiba grows today in the Kurikoma valley north-west of Send ai is hardly different from the hemp that provided fibers for the earliest textiles made by the people inhabiting the Japanese islands over two thousand years ago. The agrarian peoples of the Yayoi period are known to have used hemp and probably mulberry bark for pl ai ted and later woven cloth. With the importation of many Korean and Chinese artisans and techniques in the fourth and fifth centuries, spinning, weaving, and dyeing developed rapidly. By the Nara period, textile craftsmen in the capital had been organized into guilds under imperial and governmental patronage. Artisans were also sent out into the provinces in 711 to teach weaving and dyeing throughout Japan. Eighth century fabrics that rem ai n indicate that indigo was in use, the Polygonium tinctorium plant having been imported from China. As fine silk and cotton weaves proliferated, durable hemp materials were used by all classes.

"That asa growing so prettily in my plot up on the hill in June grew to be six shaku high (1.7 meters), lots taller than I am," Mrs. Chiba expl ai ned as she jumped up spryly to indicate its exact height, one long fingered hand held high above her head. "We gathered the asa a few weeks ago, and I have just come from stripping off the skin down there in the paddy-field water. I'll clean the bumps off the bark on that plane there and then rinse off the strips and hang them up to dry." Bamboo poles draped with the long, buff-colored fibers hung beneath the veranda eaves of the m ai n house. Next door is the small workshop-cottage in which Mrs. Chiba spends most of her time.

"This asa is very tough stuff. To soften it up before I spin it, I cook it in salt water and then in the water we pour off rice when we wash it. This bleaches it too, but I have to beat it by slapping it ag ai nst the floor to get it soft enough to spin. Spinning takes a long time—my daughter and I do most of the spinning in the winter on those old spinning wheels just like the ones they used in the old days. It takes five basketfuls of thread to weave one bolt of kimono cloth and that's a lot of thread to weave, I'll tell you that. My daughter and I can spin enough for about four or five tan (bolts), and that is all we have time for. Once we spin it, we reel it around those baskets, those ones shaped like eel traps. We can soak the thread in water right on the baskets. I need wet thread for the weft. The warp has to be dry, you know, but the bobbins for the weft I keep wet and that makes a stronger cloth. This asa is very strong. Why, it'll last for three hundred years or so, or at least more than a hundred."

Mrs. Chiba's joyous account of preparing the hemp thread was punctuated frequently by her rolling laugh, the seldom encountered laugh of a truly happy person. Her enthusiasm for what she does is so clear in her vivacity and high spirits that anyone who has met her smiles at the very mention of her name. Her face is a network of cheerful wrinkles, her eyes are bright. Although she is slightly bent now and stands well under five feet, her mind is young and sharp.

"I used to be very tall," she s ai d with a hearty chuckle, "That's why my hands are still so big I guess, but I've shrunk. I keep healthy by working. I eat everything - everything is delicious here - good rice, good vegetables. The only things I don't touch are sake and tobacco. I wake up about four in the morning and just w ai t for it be five so I can get up and get to work. I usually go to bed early, but do you know that sometimes I even switch on the electric light over my loom and weave as late as eleven at night? I like sumo and watch it once in a while, but most of that stuff on television is pretty bad, especially some of the naked dancing. Even if I can't under-stand what it's all about, I always listen to the news on the radio. I'm like a frog in a well - I'm just too busy where I am to hop out and go anywhere else. Oh, I've been to Send ai and once to Matsushima, but you know, I just can't get away. There's always so much to do here. My daughter has learned how to do most of this, but I still have to be right here to make sure it's all done correctly. Oh, it's a mighty difficult way to dye cloth, I'll tell you, mighty difficult," she s ai d with that wonderful laugh lighting up her face.

"We're getting the seeds ready now for planting next year's crop of ai (indigo) in June, and all those bags up on shelves over the dye tubs are full of dried ai leaves. We pick the ai in late July, the second crop in September. It has nice pink blossoms, you know. We strip off the leaves and then I crumple them up and put them on rice-straw matting out in the sun to dry. In good weather, three days is enough. Then we store it in those net bags. I filled sixteen bags this year.

"But the bad summer weather ruined four bags. Mother was so un-happy I just couldn't look her in the face," her daughter, a bespectacled woman in her fifties, interjected. "She was miserable to have lost some of that ai - I just couldn't look her in the face -it was really dreadful." Ignoring her daughter's mournful interruption, the old lady continued. "I'll explain our work as many times as you like, but you'll just never understand it until you do it. People can read about it, watch it, but they still don't get it. I say, better than trying to learn it, do it. Well, as I was saying, once the leaves are dry, we store them until January. We make the dye when it's very cold, and oh, it really does get cold here in January. But it's nice here in the winter, nice and quiet. Right after New Year's, I make a sort of bed out of lots of rice straw right down on the floor in front of the dyeing tub. Then I stuff some big bags made out of rice straw matting with the ai leaves that have been washed in water but left wet. You have to stuff the bags full but not too much. Too little is no good either, just the right amount. We wrap the bags in more rice straw, put weights on top and let the bags sit here on the dirt-floored section of the workroom. In a week, the leaves start to ferment, but I leave the bags without peeking in them for twenty days. Then I open up the bags and stir those fermenting leaves around very well - you have to be sure to give them a really good stir. Then, wrap them up again and put the stones or weights back on. The leaves have to sit like that for one hundred days altogether. The next job is to pound the leaves just the way you pound rice to make rice cakes at New Year's. We pound them with a wooden mallet in a stone mortar, in several batches, until it gets all into a ball. I break up these cakes of indigo paste into bits, about the size of a plum, and set the lumps out to dry for three to seven days, depending on the weather. And there you are -those are the ai-dama ("indigo balls") that make the dye, just the way they did it in the old days!”

In addition to preparing the balls of indigo, Mrs. Chiba devotes some of the winter months to spinning and starts the weaving on her simple loom. Settling herself on the narrow plank seat of her low loom, she wove several inches, smiling the entire time. The huge shuttle, shiny from use, flew back and forth across the width of hemp; the two foot-rods controlling the harnesses clacked up and down; Mrs. Chiba's pull on the beater and its percussive bang punctuated her vigorous movement.

Chiba at her loom.

"How many threads in the warp? I don't know. I do it by feel - I just string out enough to make the cloth wide enough. Laying the warp is quite a job, but once that's done, the weaving is easy. It's just that I never seem to have time to spend a whole day at the loom. So much to do. Leaves to pick and then to turn; fibers to strip; guests to greet. You'd be surprised how many people come here to learn how to do this, but they'll just never know how unless they do it. I watched my parents do it, but I never knew how to do it until I just did it!" Mrs. Chiba explained that the stacks of charcoal by the house were oak wood. The charcoal would be burned in the irori (open hearth) and hibachi (brazier) in the m ai n house all winter, as the ashes would supply the lye for the dye. "Not those white ashes, but those black bits at the bottom. We tried buying lye but it was no good, so we make it ourselves.

"I pray to the god of ai when I pick the indigo, and lots of other times too, especially when I'm making the dye," Mrs. Chiba s ai d. "That wooden tub really is a bathtub but it's clean, had never been used when I got it. I measure out the ai -dama and lve by weight, five parts to four. Then I pour in warm water - not too hot, not too cold, just right - just enough to cover the ai and lye. Then every day for a week I pour in a little more water - it can be hotter - until I get just the right amount. Too much is no good. Then I stir it very carefully and cover it. It has to sit for thirty days and then it's ready."

In order to dye a roll of the buff-colored hemp material, Mrs. Chiba inserts twelve flexible bamboo ribs along the selvage of the bolt, dips it into water, and then dips it into the vat of dye. "I put it in once for just the right amount of time - a few minutes - then take it out and let it drip back into the tub. Then in again, and once more. Once the dripping stops, I hang it up to dry. Once it dries, I give it three more dips. I do this dipping and drying six times, sometimes nine times, for each bolt of material. You see, I told you it was a difficult way of dyeing, didn't I? Just like in the old days!" she said laughing merrily. "Ai is really very strange stuff. Dyeing the cloth in ai toughens it and the ai also keeps it bug proof. Ai is very tricky to work with, you know. When I lift the cloth out of the vat, it's sort of green, but in the breeze it turns blue - right in front of my eyes it changes color. Then when the cloth has had the six or nine dyeings, I put it away. And do you know that that color deepens? It's remarkable. It gets to be a wonderful black-blue. If you put it away for six years or even three, the color will be just wonderful. It's amazing!"

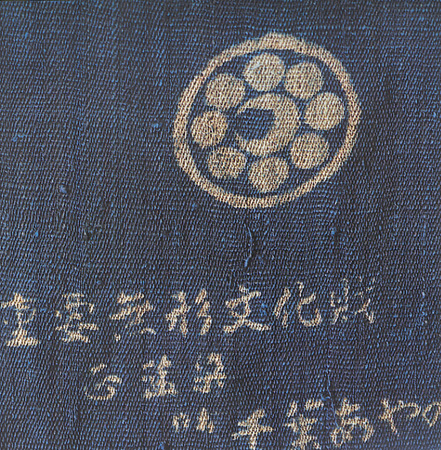

Cloth sample. Mrs. Chiba uses two wooden vats, the one made originally as a bathtub, which she bought when an old vat suddenly disintegrated, and the round wooden cask the village gave her to commemorate her designation as a Living National Treasure in 1955. She also uses an earthenware pot for dyeing small things such as skeins of wool or small pieces of cotton broad-cloth that she is often asked to dye for special orders. Once the dye is mixed in each of the containers, neither indigo nor lye nor water is added. "That's why that tub of dye is such a precious, precious thing, you see," she said emphatically. "If dust or hairs get in it, the dye is no good. But do you know that once in a while when groups come to see me we've found people putting their hands in my dye and mixing it? Isn't that terrible? Looking at the dye should be enough. Why, even I never put my hands in that dye. It's very precious. I pray to the indigo god and I'll tell you this, I keep the covers on those tubs now when I have visitors. The bubbles on it are a nice dark green. But I keep the dye covered. Imagine putting your hand into it!"

From closets and drawers and cupboards and heaps, Mrs. Chiba and her daughter brought out various photographs and books and also two large stacks of stencils. "These stencils I've just always had. I got them from a dyer and they're all very old. I just use the ones I like. We make a paste resist using the flour from the wheat that was stacked up behind the asa plants in the field. Then my daughter and I stencil undyed cotton or hemp with the paste, dry the cloth, and then dye it in the ai. When I take the cloth down to the river in front to wash out the paste, the fish come by and nibble it off. I don't wash the cloth, the fish do. It's nice in the river in the summer - not too cold, very pleasant. I wash all the indigo material there too. And I'll tell you that when I've washed it and dried it, no ai is going to come off on anyone's underwear or skin. My dye is absolutely fast, no rubbing off ever. Just as in the old days."

REFERENCE

Adachi, Barbara. "Ayano Chiba: Weaver and Dyer," The Living Treasures of Japan. Photographs by Peccinotti and drawings by Michael Foreman. England: Westerham Press, 1973.

|