THE EQUAL RIGHTS CLAUSEby Beate Sirota GordonSite Ed. Note: Included here is additional information about some of the people mentioned below in Beate Sirota Gordon’s memoir. Colonel Kades is Charles Kades, a prewar lawyer with the Treasury Department who very much identified with and supported the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He joined the army during the war and rose to the rank of colonel in the Civil Affairs Division of the War Department. Kades arrived in Japan in late August 1945 with important Occupation policy guidelines generated in Washington D.C., including the final drafts of the initial policy document, State/War/Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC) 150. He was appointed deputy chief of the Government Section (GS) and became its most important officer next to General Courtney Whitney, a close friend of MacArthur from the prewar days in the Philippines and a charter member of the inner circle, the “Bataan Club.” Before arriving in Japan, Whitney had headed civil affairs in the Philippines after U.S. forces retook the islands in 1945. Col Roest was Pieter K. Roest, head of the Political Affairs Division of GS and an anthropologist in prewar life; Dr. Wildes was Harry Emerson Wildes, who had taught in Japan in the mid-1920s and had expertise in public opinion research. Both were much older than their newly arrived twenty-two year old colleague. There is a copy of the MacArthur note referred to below in the Charles Kades Collection, University of Maryland. Technically speaking, the GS team drafted a model constitution for the Japanese, not the constitution per se. In the end, the final version was close to but not identical to the draft produced on February 12. There was some leeway for revision, and the final language was also subsequently changed to more idiomatic Japanese. The Charles Kades and Justin Williams Collections, University of Maryland, contain valuable documents illustrating the making of the model constitution and debate in the newly elected Lower House, including many women representatives, during the summer of 1946. Beate Sirota Gordon’s reminiscences are a valuable source in tracing the creation of the present Constitution of Japan but must also be tested with historical rules of evidence.

February 4, 1946, was a cold Monday in Tokyo. A harsh wind blew, and week-old snow lay in grimy patches among the ruins. Here and there wisps of smoke rose from the air-raid shelters that many families were using as homes. Most of those whose houses had burned down in the raids had gone to stay with relatives outside the city, but these people obviously had no one to take them in. After more than a month in the city, I was still saddened by the sight of meager breakfasts being cooked in the mornings and hungry children wrapped in futons poking their heads out of the shelters. And these were the lucky ones. Some families had no breakfast at all. As usual, I left my billet at the Kanda Kaikan at 7:30 and walked to the Dai-Ichi Insurance Building opposite the Imperial Palace moat. At 7:55, when I arrived, I sensed something different in the air in the former ballroom that served as our office on the sixth floor. My cheerful "Good morning!" met with silence. It was soon apparent that the "upper crust" of the Government Section, Col. Kades and his top assistants, who often arrived a little late, were already hard at work. Puzzled, I went to my desk and started working too. The first phase of the political purge, which had been announced on January 4, was being administered by the Government Section, and I was well into my assigned task of researching minor political parties and women in politics. At ten o'clock, the twenty-five members of the Government Section (everyone except the group overseeing not-yet-independent Korea) were summarily ordered to assemble in the adjacent conference room. It was not a very large room, there were not enough chairs, and about half of us had to stand. Ruth Ellerman, the oldest of the six women on the staff, was ready with her notebook in her hand.

Gen. Whitney appeared, confirmed that everyone was present, then addressed us.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he said. "Today you have been called here as a constituent assembly. General MacArthur has given us orders to do the historic work of drafting a new constitution for the Japanese people." The atmosphere was electric. Whitney, then forty-nine years old, was MacArthur's closest adviser and had taken over as head

of Government Section on December 15, ten days before I was assigned there. He now produced a memo and proceeded to read it aloud. This memo, later dubbed "the MacArthur Note," contained three principles:

I. The Emperor is the head of state. His succession is dynastic. His duties and powers will be exercised in accordance with the Constitution and responsible to the basic will of the people as provided therein.

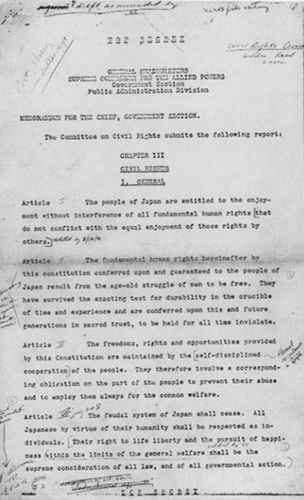

II. War as a sovereign right of the nation is abolished. Japan renounces it as an instrumentality for settling its disputes and even for preserving its own security. It relies upon the higher ideals which are now stirring the world for its defense and its protection. No Japanese Army, Navy or Air Force will ever be authorized and no rights of belligerency will ever be conferred upon any Japanese force. III. The feudal system of Japan will cease. No rights of peerage except those of the Imperial family will extend beyond the lives of those now existent. No patent of nobility will from this time forth embody within itself any National or Civic power of Government. "This draft," Whitney continued, "must be finished by February 12, when we're required to submit it for General MacArthur's approval. On that date the foreign minister and other Japanese officials are to have an off-the-record meeting about the new constitution. We expect that the version produced by the Japanese government will have a strong rightwing bias. However, if they hope to protect the Emperor and to maintain political power, they have no choice but to accept a constitution with a progressive approach, namely, the fruits of our current efforts.>"I expect we'll manage to persuade them. But if it looks as though it might prove impossible, General MacArthur has already authorized both the threat of force and the actual use of force.>"Our objective is to get the Japanese to change their ideas on constitutional revision. They must agree to accept this kind of liberal constitution. They must, in short, cooperate with our aims. The complete text will be presented to General MacArthur by the Japanese for his endorsement. General MacArthur will then announce to the world that he recognizes this constitution as the work of the Japanese government." I knew nothing about the Japanese constitutional drafts at that time, but it was clear from talk around the Government Section that the kinds of reforms that had already been proposed to the Japanese government by the Occupation authorities had triggered sharp dissension.>"We will suspend our regular activities," Whitney concluded. "And remember, what you write during this coming week is to remain top secret." He headed back to his office, leaving the staff buzzing. Already mindful of the injunction to secrecy, however, we buzzed quietly. Col. Kades now took charge, explaining how the work would be broken down and who would be assigned to what. Kades himself was to run the Steering Committee, which would include Lieutenant Colonel Milo E. Rowell, a constitutional expert, and Commander Alfred R. Hussey, head of the Legislative Division. Seven other people were assigned to chair the other committees, one of which, the Civil Rights Committee, was to be headed by Col. Roest. Dr. Wildes and I were listed as members. I felt a little shiver of pride at that moment as I thought of my parents' hopes for me. Of course, one week was far too little time in which to write a new constitution, but the feelings of excitement and idealism that everyone seemed to share swept all such worries aside. There would always be time for repairs; hadn't the U.S. Constitution itself undergone countless revisions? Still, it was an enormous undertaking. I listened in silence to the scholarly discussions that immediately broke out on civil rights and the limitations to the Emperor's powers. At the age of just twenty-two, I was in awe of all these specialists; what little I knew of such matters came straight from my high school social studies classes. Despite or perhaps because of this, I felt a tremendous sense of mission and was determined to do my best. I was also encouraged by the feeling that both Col. Roest and Dr. Wildes trusted me.

The practical business of producing a draft required each committee to divide up the work that fell to it. The matter was sometimes decided quite summarily.>"You're a woman; why don't you write the women's rights section?" Col. Roest said to me. I was delighted.

“I'd also like to write about academic freedom,” I said boldly.>"That's fine," Roest smiled. I had been given a plum, and here I was already demanding another. But I welcomed the responsibility, feeling all the more committed. What kind of provisions would be necessary to secure the rights of Japanese women? It struck me at once that the best approach to the problem would be to read other constitutions. My research experience at Time stood me in good stead here. I got Roest's permission to leave the building and quickly requisitioned a jeep and driver from the motor pool so I could visit various libraries in Tokyo. Within a few hours, I had collected a dozen or so books containing the texts of a whole range of constitutions, including those of the Weimar Republic, France, the Scandinavian countries and the Soviet Union, as well as the U.S. Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. I was amazed that these books were still available in a city that had been so thoroughly bombed, especially since some of them were in English. When I returned to the office, my arms full, the whole Government Section flocked around me. "These are great sources," people said. "Can I borrow this for a while?"

My sudden popularity acted like a shot of adrenaline. I read all afternoon, along with everybody

else in the section. As we sat there silently turning pages, we could have been students cramming for a particularly important exam. A scanty lunch was served on the seventh floor, but by evening I wanted a proper dinner, so I

put away my books, documents and memos in the safe and left for the Kanda Kaikan. As I made my way down the narrow aisles between desks, other staff members were still immersed in their work. In February, it is dark in Tokyo by 6:30. I walked briskly, a cold wind on my face, but I didn't

get back in time for the seven o'clock dinner hour. That night my head was full of thoughts about drafts and constitutions, and I slept fitfully. Being hungry certainly did not help. Tuesday, February 5At eight o'clock the next morning when I entered the office in the Dai-Ichi Building, the stale smell of cigarettes hung in the air. All morning long, I plowed through constitutions and made notes. The Weimar and Soviet documents were the most intriguing. The Soviet Constitution, for example, had been enacted in 1918, on the heels of the revolution, and spelled out specific rights for women. The U.S. Constitution I had studied at the American School, but rereading it now I saw that civil rights were not protected by the original document of 1789, but only later, in amendments. Women's suffrage, for example, was not guaranteed until 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

While I read, I tried to imagine the kinds of changes that would most benefit Japanese women, who had almost always married men chosen for them by their parents, walked behind their husbands, and carried their babies on their backs. Husbands divorced wives just because they could not have children. Women had no property rights. It was clear that their rights in general would have to be set forth explicitly. I went through my notes and underlined the points I believed it would be essential to spell out: equality in regard to property rights, inheritance, education and employment; suffrage; public assistance for expectant and nursing mothers as needed (whether married or not); free hospital care; and marriage with a man of her choice.

Washington had provided guidelines in the form of broad statements of principle, which could be construed as authorizing such things, but neither the MacArthur Note nor the old Imperial Constitution mentioned civil rights even in passing. It would be our job to introduce the concept to Japan in a detailed and concrete way. Formulating a text proved to be a complicated business. Linguistic pitfalls abounded. It turned out, for example, that language frequently used to provide legitimate exceptions in civil rights guarantees—"except as provided by law"—had been used wholesale in Japan in the past to violate civil rights. It was daunting to think we had only a week to get it right. By the afternoon, Underwood typewriters were clacking all over the former ballroom. As soon as I decided to make "Men and women are equal as human beings" the key words, I turned to my typewriter as well. As I saw it, my mandate was to ensure that civil rights and equal opportunities would be articulated in as practical and specific a manner as possible. The most important unit in human relations, it seemed to me, was the family, and within the family the most important element was the equality of men and women. “The family is the basis of human society," I began, "and its traditions for good or ill permeate the nation. Hence marriage and the family are protected by law, and it is hereby ordained that they shall rest upon the undisputed legal and social equality of both sexes, upon mutual consent instead of parental coercion, and upon cooperation instead of male domination. Laws contrary to these principles shall be abolished, and replaced by others viewing choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes." I went over my typed article many times, trying to ensure that I had covered the rights of wives adequately and in such a way that there could be no legal misinterpretation. I even consulted the relevant Japanese Civil Code. Although I spoke Japanese fluently, my reading and writing were far from perfect, but, using a dictionary and commentaries, I read the old code carefully. "Women are to be regarded as incompetent," stated Article 4. They could not sue, they could not own property; they were, in effect, powerless. Naturally, they did not have suffrage. [NOTE: Neither did most Japanese men in 1898, but in 1925, universal manhood suffrage became law.] On October 11, 1945, Gen. MacArthur had decreed, among other things, the emancipation of women and their right to vote. A look at the past reveals what a revolutionary change this was for Japanese women. Women do not feature prominently in Japanese history. They started off auspiciously: Amaterasu, a goddess endowed with supreme authority, is the first deity recorded. A handful of empresses have graced the imperial line, and the Heian period (794-1192) was a kind of literary golden age for women, its most notable figure being Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genii. But even then their social position was entirely subservient to and dependent on that of men. Later, when the samurai established the shogunate, it declined even further. Women were little better than chattel to be bought and sold. Col. Kades thought it might be a good idea to refer to the Meiji Constitution of 1889 in writing the draft, but to me it was useful only in emphasizing the need for change. It accorded the Japanese people the status of subjects of the Emperor, with very limited privileges. The provisions for religious freedom were conditional, for instance, and there was no mention of national responsibility for health and welfare. If the Emperor's male subjects were so little regarded, one can imagine how lowly the position occupied by women was. In the end, the model for my draft text on women's rights was the 1919 Weimar Constitution, a progressive document that saw marriage as based on the equal rights of both sexes. It was the duty of the state to promote social welfare policies supportive of families, and motherhood was guaranteed government support. As a woman, I felt that my participation in the drafting of the new Japanese Constitution would be meaningless if I could not get women's equality articulated and guaranteed with similar precision. I don't know how many times I revised my draft. I kept changing the wording, inserting phrases in pencil and typing it again. Every time I reread it, new ideas came to me. When I finally looked up, I saw that it was dark outside. Cigarette smoke swirled up toward the high ceiling. I got up and opened a window. The night air touched my face, and I could see the shadowy bulk of the Imperial Palace looming opposite. My watch read six o'clock. If I didn't get back to the Kanda Kaikan in time, I would miss dinner again. Feeling that I had accomplished something genuinely important, I decided it would be all right to stop, even though the others were all still at their desks and Col. Kades was still writing. Wednesday, February 6Someone brought in a newspaper dated February 5, which carried a small article about the Japanese government's efforts to write a new constitution. Working since January, it reported, Home Minister Matsumoto had prepared an article-by-article explanation of drafts A and B of a proposed revision. A Cabinet meeting that day was to discuss it. There was no hint in the piece that GHQ was in any way involved in these matters; the Government Section had apparently been successful in keeping its work "top secret." I had not even phoned my parents recently, knowing I would be unable to answer questions about what I was doing at work.

After reviewing the draft I had written the day before, I turned to the specific issue of the rights of mothers. "Expectant and nursing mothers," I wrote, "shall have the protection of the State, and such public assistance as they may need, whether married or not. Illegitimate children shall not suffer legal prejudice but shall be granted the same rights and opportunities for their physical, intellectual and social development as legitimate children." It was my understanding that if I wrote specific women's rights into the constitution, legislators would not be able to disregard them when devising the new Civil Code. I knew that the vast majority of the bureaucrats likely to be responsible for wording the provisions of the new code would be men, and conservative men at that, especially in their attitudes toward women. The Japanese women who had attended my mother's parties in the old days had often talked about mistresses and adopted children. I remembered one of them saying, with raised eyebrows, "Mistress and wife live side by side in that house." "What a terrible thing," my mother had replied. They talked angrily of men who, without bothering to ask their wives, brought home and then adopted children they had fathered outside marriage. "If it were me, I might even have agreed to it, if I'd at least been consulted," one woman said.

I wrote: "No child shall be adopted into any family without the explicit consent of both husband and wife if both are alive, nor shall an adopted child receive preferred treatment to the disadvantage of other members of the family. The rights of primogeniture are hereby abolished."

Poorer children were often deprived of an education. Among our neighbors in Nogizaka was a German bachelor who had his Japanese housekeeper and her children living with him. One of her sons was a particularly good student, and the German paid his tuition all the way through college. Remembering this boy now, I wondered what would have happened to him without our neighbor's support. I continued: "Every child shall be given equal opportunity for individual development,

regardless of the conditions of its birth. To that end free, universal and compulsory education shall be provided through public elementary schools, lasting eight years. Secondary and higher education shall be provided free for all qualified students who desire it. School supplies shall be free. State aid may be given to deserving students who need it."

I remembered the friends I had played with in Nogizaka, tossing lumps of coal about in the

street on cold winter days. As the scene came back to me, I saw again the boy with the runny nose, one of his eyes inflamed by trachoma, and the girl with a cheek swollen by toothache and wrapped in a towel, gamely playing hopscotch.

"The children of the nation, whether in public or private schools, shall be granted free medical,

dental and optical aid," I wrote, drawing on an article in the Soviet Constitution. "They shall be given proper rest and recreation, and physical exercise suitable to their development."

Through my mother and our housekeeper, Mio-san, I was aware that, before the war, farmers

Had been known to give away their children in order to cut down on the number of mouths to feed. Such children were forced to leave school and earn their keep; their only pay was a kimono every six months. During famines, girls were sold off. Col. Roest used to mention this at meetings. There should be a place in the constitution for children's rights, too, I thought.

"There shall be no full-time employment of children and young people of school age for wage-earning purposes, and they shall be protected from exploitation in any form. The standards set by the International Labor Office and the United Nations Organization shall be observed as minimum requirements in Japan." That evening I made it in time for dinner at the Kanda Kaikan, and then returned to work. Other people, too busy to leave, were eating sandwiches in the seventh-floor cafeteria. Everybody was working late. Our typist, Edna Ferguson, and I finally returned to our billet at ten o'clock, but most of the others stayed on.

Thursday, February 7A fierce wind was blowing from the west, out of Mongolia. Feeling impatient, I went to the office earlier than usual. The others must have been similarly affected, since almost everyone was there. Some of the staff had worked through the night. Both Roest and Wildes were red-eyed. I had completed a draft of the section on women's rights, as well as the clause on academic freedom,

in the space of two days. I sat down and read what I'd typed, edited it, typed it again, and waited to show it to my colleagues. While waiting, I looked through the various constitutions again to see if I had missed anything. Believing that this was a chance Japan would never have again, I wanted to be sure not to omit a single thing that might benefit Japanese women in the future. Roest and Wildes labored on at their desks, beyond distraction. As they finished each page, they

handed it to Miss Ferguson to be typed. Dr. Wildes had been a journalist, a professor and an editor, and thought himself a stylist; unfortunately, he was forever adding words and phrases to pages that had already been done, imposing quite a burden on the typist. I felt sorry for her. By the end of the day, our committee had not yet finished its draft, since Roest and Wildes were

still adding to the text. Our deadline was February 8—tomorrow. Roest, who as committee chairman bore the responsibility, showed signs of tension and fatigue. .

Friday, February 8The early morning sky was overcast, with snow predicted before nightfall. The meeting with the Steering Committee was set for today, which meant there was a good chance I would be going home late, in the snow. I took a big scarf with me. After four days without enough sleep I felt exhausted. I thought I would wait for a jeep to pick me up in front of Kanda Kaikan, but I was afraid that it would be full and I wouldn't get a ride. I saw streetcars going by packed with people. I thought of taking one, but rejected the idea, since I knew they were off-limits to Occupation personnel. So I set off again on foot. The big front doors of the Government Section office were closed. Using a side entrance, I

found Roest and Wildes still correcting their drafts, showing signs of having worked all night. Off to one side, Miss Ferguson was already typing. There were to be three copies of the draft for the Steering Committee, double-spaced to Allow for changes. Since there was no such thing as a Xerox machine in 1946, we made carbon copies. Mistakes had to be erased on all copies, so we always had carbon-stained fingers. Finally, by mid-morning, our drafts were ready. The Steering Committee room was full of cigarette smoke from the previous meeting when we entered. The committee members, Kades, Rowell and Hussey, were waiting for us, along with Commander Guy Swope, an expert on administration. Ruth Ellerman stood by, notebook ready. As he presented our voluminous forty-one-item draft, Col. Roest sighed and said, "There's quite a lot of it, I'm afraid." We felt a twinge of foreboding, which turned out to be warranted.

There were disagreements from the outset. The Steering Committee rejected an article that

reserved general unspecified rights for the people. They took out an article forbidding members of the clergy from entering politics and another one restricting the grounds for dismissal of teachers. They also objected to an article that stated, "No future constitution, law or ordinance shall limit or cancel the rights guaranteed in this constitution." By the time it was my turn to discuss the various articles I had drafted, it was one o'clock. The three-man committee read my text in silence, while I sat with the palms of my hands

beginning to get damp. The reaction came quickly and quietly. "Your basic point, that says ‘marriage and the family are protected by law, and it is hereby

ordained that they shall rest upon the undisputed legal and social equality of both sexes,’ is good, but in general the draft should be more concise." I was encouraged, but a sigh of relief was premature. The committee went on to dissect, minutely and critically, each of the articles I had contributed to the draft. Articles 19 to 25, concerning social welfare, embodied my heartfelt wish that women and underprivileged children in Japan should benefit from such important rights as free education and medical care. Col.. Kades raised his eyes from the draft and looked at me.>"Concrete measures of this sort may be valid," he said, "but they're too detailed to put into a constitution. Just write down the principles. The details should be written in the statutes. This type of thing is not constitutional material." I argued that the bureaucrats who would be assigned to write those statutes for the Civil Code would undoubtedly be so conservative they could not be relied on to extend adequate rights to women. The only safeguard was to specify these rights in the constitution. But it was no use: the committee continued to insist on wholesale cuts. Feeling outnumbered, I nevertheless tried again.

"Colonel Kades, social guarantees are common in the constitutions of many European countries. I believe it's particularly important to include this sort of stipulation here because up to now they had no such thing as civil rights." Roest lent me his support. "It's true," he said, "legally women and children are the equivalent of chattel in today's Japan. At a father's whim, preference may be given to an illegitimate child over a legitimate child. When the rice crop's bad, some farmers actually sell off their daughters." "But even if we do put in rights for expectant and nursing mothers and adopted children," Swope objected, "conditions won't improve unless the Diet enacts the laws that will implement them." To this, Wildes replied: "That's true. But we can make certain that the Japanese government is committed to doing that. It's absolutely necessary. Infringement of civil rights is an everyday affair in Japan. There's a word for `people's rights' in Japanese, but `civil rights' doesn't exist." Before I could add anything to this, Rowell cut in.

"It isn't the Government Section's job to establish a perfect system of guarantees," he said categorically. "If we push hard for things like this, we could well encounter strong opposition. In fact, I think there's a danger the Japanese government might reject our draft entirely."

Flushed and agitated, Dr. Wildes resumed the argument.>"We have the responsibility to effect a social revolution in Japan, and the most expedient way of doing that is to force through a reversal of social patterns by means of the constitution." In answer to this seemingly unanswerable claim, Rowell said:

"You cannot impose a new mode of social thought on a country by law." Even though it was apparent to everyone that GHQ was changing many of the old ways of Japan,

we had no effective counterargument to this. Much of what I wanted to say remained unspoken. It was like being in court, but a military, not a civil, court, and the Steering Committee ultimately had the upper hand. They started to cut out the women's social welfare rights one by one. With each cut I felt they

were adding to the misery of Japanese women. Such was my distress, in fact, I finally burst into tears. That Col. Kades, whom I respected so much, should fail to accept my point of view was a major disappointment. While I wept he patted me on the back, but he remained adamant in his rejection of my proposed text. The discussion went on late into the night, but we didn't even get halfway through our draft. The

basic disagreement on social policy was so serious that the Steering Committee felt they should take it up with Gen. Whitney. His decision was to leave out detailed policies and to include instead a general statement providing for social welfare protection. This confirmed Kades's view. The upshot was that my articles 17 and 18, as listed below, were left more or less intact, though shortened, but all the others (19 through 25) were eliminated.

III. Specific Rights and Opportunities 17. Freedom of academic teaching, study, and lawful research are guaranteed to all adults. Any teacher who misuses his academic freedom and authority shall be subject to discipline or dismissal only upon the recommendation of the national professional organization to which he belongs or in which he has a right to membership. 18. The family is the basis of human society and its traditions for good or evil permeate the nation. Hence marriage and the family are protected by law, and it is hereby ordained that they shall rest upon the undisputed legal and social equality of both sexes, upon mutual consent instead of parental coercion, and upon cooperation instead of male domination. Laws contrary to these principles shall be abolished, and replaced by others viewing choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes. 19. Expectant and nursing mothers shall have the protection of the State, and such public assistance as they may need, whether married or not. Illegitimate children shall not suffer legal prejudice but shall be granted the same rights and opportunities for their physical, intellectual and social development as legitimate children. 20. No child shall be adopted into any family without the explicit consent of both husband and wife if both are alive, nor shall any adopted child receive preferred treatment to the disadvantage of other members of the family. The rights of primogeniture are hereby abolished. 21. Every child shall be given equal opportunity for individual development, regardless of the conditions of its birth. To that end free, universal and compulsory education shall be provided through public elementary schools, lasting eight years. Secondary and higher education shall be provided free for all qualified students who desire it. School supplies shall be free. State aid may be given to deserving students who need it. 22. Private educational institutions may operate insofar as their standards for curricula, equipment, and the scientific training of their teachers do not fall below those of the public institutions as determined by the State. 23. All schools, public or private, shall consistently stress the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, justice and social obligation; they shall emphasize the paramount importance of peaceful progress, and always insist upon the observance of truth and scientific knowledge and research in the content of their teaching. 24. The children of the nation, whether in public or private schools, shall be granted free medical, dental and optical aid. They shall be given proper rest and recreation, and physical exercise suitable to their development. 25. There shall be no full-time employment of children and young people of school age for wage-earning purposes, and they shall be protected from exploitation in any form. The standards set by the International Labor Office and the United Nations Organization shall be observed as minimum requirements in Japan. I do not remember when we finished the discussion that day, I only remember the coffee we drank and the cigarette smoke. I don't even remember eating dinner. When I went back to my desk in the ballroom, everybody was still working, their eyes now chronically bloodshot.

I headed home. The wide road was blanketed with snow, as had been forecast. From inside the hooded jeep I stared at the swirling flakes. I was still too upset to repair my makeup, ruined by tears. To this day, I believe that the Americans responsible for the final version of the draft of the new constitution inflicted a great loss on Japanese women.

Saturday, February 9The weather that weekend was very cold, with unusual amounts of snow for February. The grounds around the Diet, which had come through the bombing unscathed, looked like a winter scene painted by an old master. To add to the general misery of the Japanese, bad news seemed to be coming as thick and fast as the snow that now lay heaped up around the city. The newspapers that week had reported the suffering of women and children living in schools that had survived the raids. Prices had gone up four hundred percent. The black market was thriving. General Yamashita, the former commander in the Philippines, had been sentenced to death. There was also the news that various Pacific islands, including Okinawa and Saipan, were to become trust territories of the United States.

It was warm enough in the Government Section when I went in. The Steering Committee had not had time to go over all forty-one articles of our draft on Friday, so the session was extended one day. I did not attend this part of the meeting, however, since I was working on corrections and changes to my own segment.

Roest and Wildes tried again to get as many of the social guarantees as possible into the constitution, but they were generally unsuccessful. It was interesting to see two men of such wide differences in background and personality finding themselves in such deep agreement on the matter of our draft. In view of that, I was surprised to read later, in his book Typhoon in Tokyo, that Dr. Wildes considered Col. Roest a man of little ability.

If it had been an ordinary Saturday, we would have worked until three o'clock, but the meeting ended much later. It was decided that the completed draft of the constitution would be given to MacArthur the next day, Sunday the tenth.

At that stage, the Civil Rights Committee had been left with thirty-three of its original forty-one articles, roughly one-third of the total number of articles in the proposed constitution.

On the way home late that night, the roads gleamed with ice. The week that had begun on

February 4 seemed in retrospect like a single, seamless piece. It felt as if we had been working not for six days, but for weeks.

The question arises as to why MacArthur was in such a hurry to have the constitution drafted. One reason could be that the Far Eastern Commission, made up of eleven former Allied powers, was due to be established on February 28. Since this body included countries such as the Soviet Union, Australia, New Zealand and China, which opposed the imperial system that MacArthur intended to maintain, it was important to get the Japanese government's approval of the constitution as soon as possible. In addition, a general election had been scheduled for April 10, the first since the war; it would be important to have the voters give their judgment on the new constitution, so as to conform to the Potsdam Declaration's stipulation, "... in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people."

Because of the time it would take to make and transcribe revisions, the Civil Rights Committee was given until February 12 to work on a final draft. Forty-one articles had shrunk to thirty-one by the final stage. From my specific point of view, we had at least succeeded in including a statement guaranteeing in principle the rights of women and children. In this important area, the new constitution completely superseded the Meiji document.

On the night of February 12, the full ninety-two-article draft was completed. All that

day, Gen. Whitney, the members of the Steering Committee and the heads of all the other committees had met in a last effort to perfect the document. The debate between the pragmatists and the idealists continued, with the former prevailing in their preference for a streamlined draft, but the latter very much dictating its underlying spirit. In the end, benevolence rather than vengeance emerged as the dominant principle guiding the efforts of everyone who helped frame the constitution.

The finished draft ran to twenty pages, double-spaced. Thirty copies were made and signed by the compilers and presented to MacArthur. I and two others did not sign, because we weren't present when Col. Kades called for signatures. It was very late, so late that the twenty-five of us who had worked so hard for the past week were too tired to celebrate. After nine days, the lights on the sixth floor of the Dai-Ichi Building were finally switched off, and everybody went back to their billets.

On February 13, the draft was given to Foreign Minister Yoshida and Home Minister

Matsumoto Joji [actually, Matsumoto, a lawyer, was a minister without portfolio in the Shidehara Cabinet] at the foreign minister's official residence. The American delegation, consisting of Gen. Whitney and the Steering Committee, told the Japanese officials that the draft submitted earlier by the Japanese government was completely unacceptable. In view of the Japanese draft's failure to broach the issues of freedom and democracy, SCAP was proposing that its own draft be taken as the required basis for the new constitution. The SCAP officials then withdrew to give the other side time to analyze the document.

The Japanese officials were shocked. They had expected to discuss the Matsumoto draft with the

Americans, not to be presented with an entirely different document. After they read it, they were even more shocked. When Gen. Whitney came in again to respond to their questions and objections, he pointed out that MacArthur himself was under great pressure from various quarters to treat the Emperor as a war criminal and that a new constitution, complete with all the required guarantees, could well assist him in resisting such pressure. To the Japanese, this was tantamount to a threat. The formulas guaranteeing democracy and equality, which to us were the chief end of all our efforts, were not things they could easily accept. This first meeting lasted only an hour and ten minutes. The Japanese presented a copy of the

SCAP draft to Prime Minister Shidehara, and then Matsumoto prepared yet another version, which contained no reference whatever to civil liberties. This was also rejected, as was a subsequent draft. On March 4, in a joint session designed to bring the two sides together face to face, another revised draft was presented by the Japanese. That morning, Col. Kades called me. "We can use as many interpreters as we can get," he said. "Please come to the meeting."

I was glad of the chance to see in person what happened to the civil rights articles I had written. The meeting took place at 10:00 A.M. on the sixth floor of the Dai-Ichi Building. Because of SCAP's determination that this constitution be viewed as Japanese in origin, the proceedings were designated top secret, and we were told we could not leave the building until they were over.

The Japanese contingent consisted of Home Minister [once again, in fact, Minister without Portfolio] Matsumoto, Sato Tatsuo, the head of the First Department of the Legislative Bureau, Shirasu Jiro, deputy chief of the Central Liaison Office, and Obata Kunryo Obata and Hasegawa Motokichi from the Foreign Office.

The Government Section, represented by Gen. Whitney and Kades, Rowell and Hussey, sat with the Japanese around a large table. The team of translators was headed by Lieutenant Joseph Gordon, a capable and quick-witted intelligence/language officer. I was the only woman in the room.

Matsumoto started by handing his draft to Whitney, being careful to explain that this was not a formal version approved by the Cabinet. The Japanese would be using this draft as a basis for negotiation. Col. Kades immediately turned his copy of the document over to the language team. As each article was translated, he studied it closely.

The opposing viewpoints of the two parties were clear from the outset. The very first article of our draft, for example, contained a reference to "the sovereignty of the people." The Japanese had revised it so as to remove these words. This, Kades insisted heatedly, was unacceptable. The Japanese revision appeared to be designed to preserve the exalted position of the Emperor. There were lengthy arguments about the true meanings of words preferred by the Japanese, which seemed to the Government Section to represent attempts to water down the American text. My throat became dry as I and the other translators explained the significance of numerous disputed terms. The discussions were generally polite, but tense; nobody wanted to concede anything. The Japanese side continued to maintain that the terms demanded by the Government Section were not "proper" for a constitution, and the Americans continued to disagree.

By 2:30 virtually no progress had been made. Since we were not permitted to leave the

conference room, we ate lunch at the table. We were provided with C and K army rations (C came in cans and K in boxes), both barely adequate. The discussions became more heated, until Matsumoto, fearing that there might be no room for compromise, turned authority over to Sato and left to report to the Cabinet on the gravity of the situation. That evening, Lt. Gordon noticed a literal Japanese translation of the Government Section's

English draft lying unremarked on the table near him, apparently left there by the man from the Central Liaison Office. Once Gordon realized what he was looking at, he knew that the draft put forward by the Japanese had become irrelevant. This was their way of signaling that they had given up a losing battle. They had come to the meeting prepared to surrender, but had used it to make a last-ditch effort to promote their own version. From that point on, the task of translating became easier. Discussions continued, but the rancor had eased. It was not until 2:00 A.M. that the civil rights section came under consideration. Everyone was

tired. Nevertheless, to my great surprise, the Japanese started to argue against the article guaranteeing women's rights as fiercely as they had argued earlier on behalf of the Emperor. This article, they felt, was "inappropriate" for the Japanese. Although I had been fighting sleep, I snapped awake when I heard these arguments. The Japanese had taken a liking to me, probably because I was a fast interpreter. Col. Kades,

ever sensitive to nuances in people's feelings, thought to take advantage of this to forestall further argument. "This article was written by Miss Sirota," he announced. "She was brought up in Japan, knows

the country well, and appreciates the point of view and feelings of Japanese women. There is no way in which the article can be faulted. She has her heart set on this issue. Why don't we just pass it?" There was a stunned silence from the Japanese, who had known me only as an interpreter. But to my delight the ploy succeeded. “All right,” they said, “we’ll do it your way.” The remaining articles were not accepted so readily. The so-called “Red Articles,” which gave ultimate ownership of land and natural resources to the state, met with such strong opposition that they were dropped. The unicameral system of government proposed by the Government Section was changed to bicameral. With ninety-two articles to consider, we still had a long way to go at 3:00 A.M.

Negotiations continued into a wintry dawn. More C and K rations. Soon it was ten o’clock. The air in the room was stale, and the people around the table had dark rings under their bloodshot eyes. I was finally told I could leave. When I reached my billet I fell into bed and slept like the dead.

After I left, discussions over terminology resumed. The step-by-step process seemed interminable to those who stayed, but it finally ended at 6:00 P.M. on March 5, thirty-two hours after it had begun. GHQ wanted to announce the completion of the draft immediately, but the Japanese government preferred to wait until the next day, citing the time it would take to present the new constitution to the cabinet, the Emperor and the Privy Council. On the evening of March 6, the revised draft was published as the work of the Japanese government. Gen. MacArthur announced that he was fully satisfied with the”new and epoch-making” constitution, as if he had never seen it in his life.

But it was the banner headlines in the next day’s newspapers that reflected the common reaction best: “New Constitution Draft Rejects War.” Only the article renouncing militarism really touched the hearts of people who had suffered such devastating losses.

Site Ed. note: As Sirota (soon to be Gordon) explains, her personal involvement in the constitutional process ended at this point. Subsequently, the model draft was debated by the Privy Council, the newly elected Lower House, and also reviewed by the Far Eastern Commission (FEC), which began meeting in Washington, D.C. in early March. Some revisions were made by the Japanese and the FEC. In November 1946, the Emperor promulgated the final revised draft by imperial rescript. After an extensive six month public information campaign to acquaint all Japanese with the contents of the new Constitution, it became the fundamental law of Japan on May 3, 1947. It remains the fundamental law today but is undergoing a thorough review in the Diet.

......................... ReferenceGordon, Beate Sirota. Ch. 5, “The Equal Rights Clause,” The Only Woman in the Room. Tokyo, New York: Kodansha International, 1997; pp. 103-124.

|