The Hour of [His] Feeling

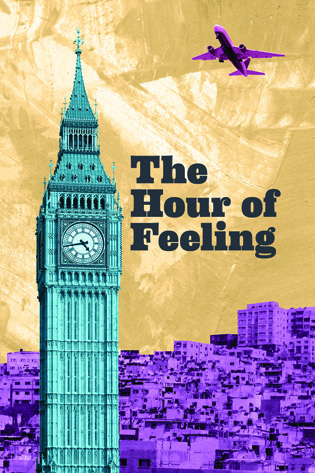

Posted by on Monday, May 14th, 2012 at 12:05 amThis March, I spent the last few days of my spring break in Louisville, Kentucky. As I may have mentioned in class, I am on the board of LMDA and for the past several years we have held our spring board meeting in Louisville during Humanafest at the Actors Theatre of Louisville. It is a wonderfully dizzying two and a half days of play-going, panel discussions, and conversations about theatre in lobbies and in restaurants. This year the festival featured works that varied in theme and genre quite a bit. My personal favorite struck an emotional chord with me that now rarely happens with a show I have not worked on, or am not personally and professionally invested in. Mona Mansour’s The Hour of Feeling is a haunting look at the meaning of home, set in 1967 in Palestine and London. I do not mean this essay to be a review of the play. You can find out more about the piece by watching this clip and reading this review (which opens with the line: “If you want to understand the Sixties, go back to the early 1800s, when Romantic poets like William Wordsworth rejected classical rationalism to celebrate the beauty of deep emotion and the sanctity of individual experience.”), and doing the usual googling routine. I am writing about the play on this blog because of the connection it has to our class materials, particularly our discussions on prosthetics of imagination and memory and gender.

The protagonist of the play is Adham, a young scholar from Palestine who has been invited to London to give a scholarly lecture on Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks o the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798.” He brings his new wife with him and, while they are in London, war breaks out in the Middle East (one they could not have known would be so short and yet so long). On the evening after his triumphant lecture, while at a party, they receive news of the war. Adham’s wife, Abir, is frantic to return home immediately. Adham is less certain that he wants to return to Palestine (known then as Jordon, “sort of”) and to his mother, who appears to him during his more introspective and anxious moments in the play.

The title of the show is from another poem from Lyrical Ballads, “Lines written at a small distance from my House, and sent by my little Boy to the Person to whom they are addressed,”[1] and selected lines from it are projected on a scrim or quoted during the course of the play (the sections in bold are the ones projected or quoted during this production):

It is the first mild day of March:

Each minute sweeter than before,

The red-breast sings from the tall larch

That stands beside our door.

There is a blessing in the air,

Which seems a sense of joy to yield

To the bare trees, and mountains bare,

And grass in the green field.

My Sister! (’tis a wish of mine)

Now that our morning meal is done,

Make haste, your morning task resign;

Come forth and feel the sun.

Edward will come with you, and pray,

Put on with speed your woodland dress,

And bring no book, for this one day

We’ll give to idleness.

No joyless forms shall regulate

Our living Calendar:

We from to-day, my friend, will date

The opening of the year.

Love, now an universal birth,

From heart to heart is stealing,

From earth to man, from man to earth,

–It is the hour of feeling.

One moment now may give us more

Than fifty years of reason;

Our minds shall drink at every pore

The spirit of the season.

Some silent laws our hearts may make,

Which they shall long obey;

We for the year to come may take

Our temper from to-day.

And from the blessed power that rolls

About, below, above;

We’ll frame the measure of our souls,

They shall be tuned to love.

Then come, my sister! come, I pray,

With speed put on your woodland dress,

And bring no book; for this one day

We’ll give to idleness.

Adham’s lecture, however, is not on this poem, but on one of Wordsworth’s more famous poems, which I’ll abbreviate here as “Tintern Abbey.” Throughout the play, Adham has several interesting discussions about the poem with other characters, especially the two scholars from University College who befriend him and play host to him. However, rather than focusing on those (albeit significant) discussions, I would like to examine a topic present in the play that we have also discussed in class in relation to other romantic works.

In class we have discussed other works where concepts about imagination and gender are intertwined. We have examined how Wordsworth took inspiration from his sister’s journals, turning her entries into, for example, his poem “A Night-Piece.” In comparing the two, we note the actor in the pieces turns from female to male, and from passive to active. Wordsworth uses Dorothy’s description of the night sky as an event of transcendence and sublimity. Dorothy is a prosthetic to Wordsworth’s imagination, in so far as he re-appropriates her more embodied writing to reach a creativity believed to be beyond a woman’s grasp.

Similarly, in Neuromancer we see Molly as a body to Case’s mind. She is the fighter, the one who actually physically ventures into danger. She is the one who has altered her body with prosthetics such as altered vision and weapons under her fingernails. She even wear a stim-sim, a way for Case to “plug in” to Molly’s body and experience the physical sensations that she feels. In the world of Neuromancer, the female is grounded, earth-bound, connected to the body and to the physical, and the male is the mind and imagination, the quest, the transcendent.

Victor Hugo too, writing a few decades after Wordsworth, in his 1827 Preface to Cromwell,[2] points to a gendering of the physical versus the spiritual, as he asserts his account of the origin of drama:

“On the day when Christianity said to man: Thou art twofold, thou art made up of two beings, one perishable, the other immortal, one carnal, the other ethereal, one enslaved by appetites, cravings and passions, the other borne aloft on wigs of enthusiasm and revery, the former always stooping to earth, its mother, the latter always darting up toward heaven, its fatherland – on that day, the drame was created. It is, in fact, anything other than this constant – on every day, for every man – contrast and struggle between two opposing principles which are ever present in life and which dispute possession of man from the cradle to the grave.” (306)

For Hugo, the perishable, the carnal, belongs to the mother, while the ethereal, the immortal, belongs to the father. This duality is essential, in Hugo’s opinion, for the birth of drama. Interestingly, and perhaps unintentionally, we see this duality, and this act of women as prosthetic, the connection of woman to body and to earth and, by extension, to place and to home, in The Hour of Feeling.

As I mentioned previously, Adham brings his new wife, Abir, with him to London (and, significantly, leaves behind his mother, who raised him alone as a refugee and was aggressive with his education, pushing him to become a scholar). Abir is a farmer’s daughter and very smart. She speaks French, though no English, and has a love of western pop culture. It is in Abir that Adham sees all of his conflicts with his culture play out. He is clearly attracted to her love of western music and film, but also expects her to be a dutiful wife, and is conservative when it comes to her desire to smoke and to drink alcohol (and to engage more fully with his colleagues in London, which is really what the other acts are symbolic of). When Adham needs to think through his anxieties about his intellectual pursuits, her conjures the woman he ran away from, his mother, rather than confiding in his wife. He draws his mother as a memory, near him in his imagination, but repels her bodily, abandoning her in Palestine and grouping her with all of the other things about his culture he finds distasteful, and would like to leave behind (he does exactly what Abir tells him he can not – pick and choose what part of his culture to take with him). Beder’s lack of bodily presence allows him to “talk” to her (and she does actually appear on stage during these moments) in his imagination. But he does not have these talks with his wife, who is actually physically present for him. She must remain embodied, connected to the earth, and separate from his scholarly transcendence, even as his mother facilitates said transcendence.

A break occurs when news of the war comes to the couple. Adham sees it almost as an opportunity to possibly abandon his home, not to return to his country but rather to become a refugee once more. But Abir, for all of her love of western culture, does not consider London her home, and must physically return to Palestine to be with her family. During their final argument, Adham says that he does not need his mother any more because she left her imprint on him forever and that she is inside of him, to be accessed when he needs her (perhaps as data in a database is accessed to form a narrative). Abir does not (or can not?) have that – London feels like “Nowhere” to her and she must be physically present in Palestine. After she has left to get on a plane to return home, Adham takes a book and read aloud a composite of lines from Wordworth’s “The Ruined Cottage” (another poem discussed in the play) while his mother, Beder, and his wife, Abir, both now appear to him in his mind, carrying their possessions in their hands, refugees now and perhaps always. He recites:

“The house-clock struck eight:

I turned and saw her distant a few steps.

Her face was pale and thin, her figure too

Was changed. …

She told me she had lost her elder child.

Today

I have been traveling far, and many days

About the fields I wander, knowing this

Only, that what I seek I cannot find.

And so I waste my time: for I am changed. For I am changed.”

Clearly it is Adham who believes he is changed. But I would ask if he truly has been changed, or if he is the one changing others. Now that Abir is not physically present, he manifests her in the same space as his mother, perhaps to formulate her as the way he would have her. To speak to her as he needs to in order to carry on his work, to decipher his dilemmas about home and tradition, and to craft his (new?) identity as he remains in this new world to make a home away from the land and culture in which he grew up and which is now experiencing an upheaval that perhaps his imagination can not fathom. Perhaps he can only imagine it through the women he loves, while they physically experience and embody the upheaval.

“From earth to man, from man to earth,

–It is the hour of feeling.”

Adham is in his hour of feeling. But he, a man, needs the earth, meaning the woman, in order to feel, to transcend, to experience the sublime. They, the women in his life, can not do so, but he can not do so without them.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.