A Thing or Two about Monsters

Posted by on Sunday, March 11th, 2012 at 8:44 pm“The body is not one, though it seems so from up here.” – Shelley Jackson, “Stitch Bitch: the Patchwork Girl.”

One thing, or many? Is a monster a fully integral creature, or literally or etymologically, several? Stitches mark the external evidence of internal division in Frankenstein’s monster, suturing together a gathering of disparate parts made animate. As the parts are ill-fit together, the monster is ill-fit to the world, internal relations forming, foreordaining outer.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge uses the chimera to illustrate the disunity he perceives in a work of literature that seems patched together. The chimera exemplifies what he calls “mechanical form” in literature, the lesser of two kinds of artistic production, the more capably integrated and naturally constructed counterpoise to which he calls “organic.” Frankenstein’s monster breaches this distinction of Coleridge’s, dissolving the boundary between an exalted formative principle and a deprecated one, between the interwoven textures of life and assembly in the style of gears and gadgets.

How stable, though, is the category of the “organic?” If something organically formed is somehow uncontrived and with better fit among its various parts than the chimera, we should be able to see how its parts make sense together.

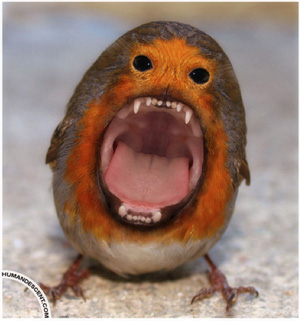

Look at this bird:

And this:

Or this:

Or the mandrill:

How could you say, if you had never seen a hornbill, or a mandrill, that these creatures’ parts fit together beyond their apparent points of attachment? The head of the bald eagle looks to me entirely out of place in its coloration and just as ill-fit to the body as the head of a chimera to its. A turkey’s head, a mandrill’s face? In their superficial anatomy, they visually clash with their bodies.

By contrast, the digital image artist Martin of Humandescent.com unites visually disparate animals’ parts, using morphing techniques to blend and metamorphose images of different creatures into graceful conjunction with one another. One of my favorites from this site is Kittguin, formed from a blend of a penguin’s body and a black-and-white kitten’s head, the color patterns of head and body assimilated with one another. Fetch! seems to have brown fur, rather than feathers, continuing the dog’s facial texture across its body, and Crog, the crow-dog, has black feathers that blend texturally with the salt-and-pepper jowls of a hound.

The techniques Martin applies in these pictures answer a question that Coleridge’s use of the chimera only implies: What is a chimera’s graphic opposite? Applied to a living creature, what does the formal transformation from chimerical to organic look like when visualized? In electronically morphed images like these, the Coleridgean chimera rehabilitated boils down to a kind of mixing or exchange of surfaces and textures, or of finer-scale parts among larger-scale ones. Taking these images as examples, a distinction of organisms from badly integrated synthetic creatures seems at least in part to be about texture and scale.

By performing these cosmetic operations on grafted-together images, though, does Humandescent.com defuse the affective potency of composite creatures, taken as monsters? Can we really call Kittguin a monster, as a grafted-together creature? Isn’t it just cute? How does Dowlog (below) look to you? Monster? Not a monster? What about Robin Red Thug? To my eyes, it is not texture per se that makes these images a little disturbing, but the presence of a head that I do not expect in its bodily context. Is it evidence of a composite status what gives Dowlog its affective impact? Or the inclusion of the almost otherworldly ferocity of an owl’s visage?

If we see a monster like Frankenstein’s as an assemblage of mismatched parts, a Coleridgean chimera brought to life, and then apply pressure to this model, we find weaknesses in it: actual organisms in the world are not always morphologically unified in the way Coleridge imputes, while visibly unified organisms, unchimerical in appearance, may still appear monstrous to us. The chimera, if taken as a model for monstrosity, has properties that turn out to be insufficient to account for monstrosity itself. But are they necessary? The abstracted, formalized idea of the chimerical does not take into account the acculturation that has made some animal forms familiar to us but others bizarre. It does not take into account the deeply embodied nature of our minds and our capacity for revulsion and fear, something we can feel so readily for loathsome creatures, unified in appearance or not. Textural unity after all does not efface the strangeness, the mismatch with expectation, that a novel creature presents. Some morphed creatures still resist unification.

It makes a kind of formal sense that a monster unassimilable to the world around it can be made of parts unassimilated to one another. Beyond this, Coleridge’s rough equation of chimerical form with mechanical has another advantage, when we turn it back on the question of what is monstrous: it gives us the kernel of an explanation of why we would see something entirely inorganic, a robot, also as a monster.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 You can leave a response, or trackback.

Your example, Philip, of the chimera, brings up some really interesting counter-thoughts to what I have been thinking about monsters. Looking back to other Greek ‘monsters’ I initially had thought of the Minotaur, centaurs, or the Sphinx. The common component of all these ‘monsters’ is that they have a humans parts. This has defined the monster for me lately because I have thought primarily in terms of abjection, and how the theory implies that humanity is an intrinsic part of the process of abjection. Perhaps this why I have difficulty, as you did, with seeing the Humandescent creatures as ‘monsters’; there are no human parts, and thus no pieces to define myself against that are different from my consideration of organic (is that the word I’m looking for?) animals.

Well, for “organic animals” I’m tempted to use the “r” word (r___). Alternatively, “organic creatures”?

That’s an interesting catch, of human parts common to the Greek mythical creatures… and temptingly consistent with theory built around abjection. With that we’ve got other stuff compiled, in tweets–where the etymological roots have been particularly interesting (was it Dan who posted about a root “to warn”?). It hovers in my mind without time materializing to try to aggregate it. Tweet aggregation could be productive… –> “Is there a cluster of meanings of this word in which fundamental parts of its meaning line up in an unexpected way?”

While my target post is an attempt to draw something out in a formal model–drawn from a monstrous Greek mythical creature, but intended to conceptualize literature rather than the way I used it–it’s guided in part by “common sense” construals and uses of the word “monster” as I have learned it, where in many cases it referred to things that were either large, powerful, or scary, or unfamiliar, or some combination of those, which seemed to be independent of similarity to human beings. There may be a systematic configuration of that part of “monster” semantics that fits tellingly into a psychoanalytic theory of abjection, but I’m not there yet. (There’s a PDF of a Behavioral and Brain Science article on a unified theory of repression, e.g., that’s going to have to wait while a lot of other stuff gets read! And with it, Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, which at this moment happens to be open but cannot get the time it deserves…)

And even with the continuing scientific controversy about psychoanalytic concepts, evident in the Open Peer Review section of that repression article just mentioned, abjection seems where it’s at for a close analysis of Frankenstein, for its conception of the monstrous. But I’m going to make myself stop there, since time to type is running out…

Principle Components Analysis of uses of “monster?” Hmm.

Really interesting stuff. Nigel’s pointing out that many mythological monsters have human parts got me thinking. I don’t have an answer to this question (I also can’t take credit for pointing out any etymologies), but one major, semi-obvious idea is what we’ve been talking about all along: the monster is something that reveals hidden truths about ourselves. This relates to the Uncanny. So we hate when a creature, what should be considered the external, resembles us or the internal. That may be why such creatures are considered monsters: they are a distortion of humanity. This rings true for our subjective views of animals in the real world. Oftentimes, we think certain creatures are cute because they are distant enough from us visually. But the moment they resemble us (an imitation), we freak out. The chimera and sphinx are obviously related to this, as are many real-world animals (though I can’t think of many besides maybe the sloth and certain species of monkeys).

On the other hand, and I think this is closer to what you’re getting at, we also consider certain creatures monsters when have no bearing or relation to us at all. This occurs, I think, when creatures are so distant from us that they are hard to understand. The hagfish (and other really odd sea creatures) or the star-eyed mole embody the bizarre in this way. H.P. Lovecraft made a (very poor) living off of writing about the completely inhuman and unhuman, making us afraid specifically because we could not relate to his monsters.

As for what constitutes a monster when we pick and choose parts from different animals and put them together, it’s really hard to say. It’s in some way related to what I’ve been talking about. Certain combinations may be pleasing to us for certain reasons, and other creatures are monstrosities. Why? Maybe they go too far in one direction, either too human or not human enough. But I think you’re right: there’s more there that I can’t seem to grasp. If only we could better define what makes something cute and what makes it a monstrous. Of course, that might be missing the point entirely.

Actually, I was thinking, my favourite Lovecraft story is the one (sorry, the title eludes me at the moment) in which the whole town are fish-humans and the stranger passing through stumbles onto their secret–and is almost killed for it!

I’ve been thinking a lot about monstrosity of late and just finished writing a paper on Frankenstein’s monster as the parasitic host–combining Michel Serres’ _The_Parasite_ and Michael Taussig’s _Mimesis_and_Alterity_. It made me consider “monsters” in a new light. Our fear of them comes in part from their uncanny combination of mimicry of ourselves and things we recognize and their inherent alterity. However, it is fascinating to consider them in terms of their parasitism. That the greatest fear their produce is that they might, in some way, devour us. Devour our humanity. Interrupt our lives. Frankenstein meant to parasitically feed off the powers of natural reproduction, rendering it in a new way with male intellect. Yet what he creates, the wretch, has the ability to feed off of him–to make a life within his own, a common space of his private one, simply by existing. The parasite becomes parasited upon. I wonder if that could be part of the fear of “monsters?” That in our fear we might create a monster more powerful than ourselves?

(1) This question of looking not to much but not too little like a human being, to be a monster, sounds an awful lot like “figurative goodness” in aesthetic judgments of metaphors. It’s been found that people find metaphors to be “good” prevalently when the word used metaphorically (the “vehicle” in some ways of viewing it–the modifying term) is drawn from a category distant from the “topic” (modified term) but… I think as it is stated, where the relations within those two categories are comparable. This requires a return to the literature to do right, to state accurately, and that means a time commitment I can’t quite afford, so I’ll leave it tentative and loose like that for now. Metaphors also inhabit a middle ground between literality so-called and nonsense, on one very loose way of framing it (there are confounds in the definition of metaphor and other stuff to take into account; Bipin Indurkhaya’s _Metaphor and Cognition: An Interactionist Approach_ addresses some of the definition troubles and the section he writes about the senses of “metaphor” is useful.). From this, I wonder if there is a middle ground of distinction that preferred animals inhabit. Wait, you said that. I mean, there may be something general in our perceptual and conceptual preferences at work here. May be. Just a guess.

(2) On missing the point entirely (productively or not): Mm. Well I’m lazy, so I’m going to put off looking into the aggregated tweets (I feel like a beetle carrying a large piece of fruit on its back, so I’m going to put off looking into the aggregated tweets). But about possibly missing the point entirely, a thought has been orbiting here for a while, and that’s about orbits in state space, as they relate to definitions and Dr. Fraistat’s paper on the question of defining the digital humanities. If you take the state of a definition to be a cluster of points or a set of variously clustered points in some kind of a state space (where each dimension of the state space is a parameter of some part of the meaning that is more or less present), then you can (in one case) end up with small, fixed points that don’t invite innovation (outside of a formal system where e.g. in mathematics you can get quite a lot out of a few axioms). Let’s say (just to say, and maybe to be wrong) that semantic space is finite, or at least maybe bounded (not infinite in extent),** so something like an energy maximum limits things.

Then you could have various kinds of trajectories through state space as you approach various meanings of a word (you could have approaches that terminate in “point attractors,” some that orbit systematically–”limit cycles”, you could have a chaotic attractor, something that never gets to a point but never wanders to every point in semantic space either, so it would be a haze or penumbra of points, yet far more specific than randomness). What interests me when I think of the word definitions we’ve considered (though it overmatches my mathematical acumen, so far) is the idea that there might be a kind of itinerant pattern of activity of mind, like what is called a “heteroclinic cycle” (with more time I’d hunt up the papers blossoming ten years or so ago on “stable heteroclinic cycles” Aha. Found it. * ). Basically a cycle like this follows a path around a heterocline (if I have that word right), a path through state space across a series of points, each of which points is a minimum in one dimension and a maximum in another (it’s also called a “saddle node” as I remember, something that describes it better for visualizing).

Maybe a definition would be itinerant and move about according to its encounter with various contexts of use. And we wouldn’t want to know what exactly a monster was, e.g. because knowing exactly, we would be unprepared for variants. *** Alternatively, maybe a definition is not something we quite ever want to find, something that should remain fugitive for us to use the word we would assign it to, freely. Like a black hole. Its event horizon, by theory and so-far consistent observation (right? or wrong?) can be observed, but the inside of which is not considered a proper holiday destination.

* Ichiro Tsuda, “Toward an interpretation of dynamic neural activity in terms of chaotic dynamical systems” Behavioral and Brain Sciences (2001) 24, 793–847. There’s also some stuff in Science where similar and related work has been reported, early in the 00′s of the present century; and probably more up-to-date stuff of comparable interest.

** Semantic space may be an overly optimistic conception of semantics, as well, suited more to neural network modeling (with that niftiest tool, linear algebra as its framework) than to naturalistic word definition; see Amos Tversky’s “Features of Similarity” in Psychological Review, 84:327–352, 1977. There Tversky presents findings that similarity measures among words prove asymmetric in many cases, so the semantic distance from A to B is not the distance from B back to A. It’s not a proper as-the-crow-flies distance. Tversky accounts for this with an attention-biased (or salience-biased) set-theoretic model called the “contrast model,” as I remember.

*** The way memory is integrated into the present experience, the way it is not like a “picture in the mind,” the way bits and pieces of percepts are dynamically reconstructed into wholes to suit the moment, and the irrelevant bits are dropped off, seems closer to an idea of why a definition would be moving about on us, as new uses reinterpret it–though maybe that’s got a state space conceptualization, and maybe it’s another way of saying something pretty much the same… None of this makes for happy propositional logic–or first-order logic, or nonmonotonic logics either, I suspect.