Among NAEB-supported programs that center the themes of economy and business, listeners will find a diverse set of aesthetic strategies, topics of discussion, viewpoints, and, to some extent, ideologies. Combined, they exhibit the major currents of economic orthodoxy under the later parts of embedded liberalism (c1930s-1970s), when the state took responsibility for counterbalancing some of the most disastrous consequences of laissez-faire economic policy.

If, as Mark Blythe argues, ideas rather than existing economic conditions lead 20th-century policy decision-making, then these recordings are essential listening for anyone seeking a better understanding of how the seeds of economic and political transformation sprout—and what they sound like (Blythe, 10).

Two of the earliest series presented here, Fifty Years of Growth and Document: Deep South, share much in common with institutional advertising, whether radio predecessors (DuPont’s Cavalcade of America), televisual contemporaries (National Association of Manufacturers’ Industry on Parade), or the mass of sponsored films shown just about anywhere someone could get their hands on a projector. Although Years centers on potentially unnerving tensions (will employers and workers compete or collaborate?), each episode concludes with a promise of better living through chemistry, consumption, automation, and whatever else business might take credit for.

Document: Deep South offers a regionally-accented rehearsal of Years’ same “growthmanship” logic, which holds that continuously increasing the overall size of the economy—rather than redistributing resources—would solve social ills; a rising tide lifts all boats, so the saying goes (Collins, 20). An aurally evocative docudrama that investigates a different industry (timber, textiles, farming) in each episode, Deep South suggests that no community will be excluded from the bounty of America’s rising tides. (As to the impact of rising sea levels caused by all this growth, Pollution Explosion offers a multifaceted look at the causes and consequences of increased consumption and lax regulation, as well as snapshots of successful and failing cities.) Given its promise of shared prosperity, Deep South centers the experience of white southerners, carefully trimming its timeline of progress to eliminate overt references to slavery and its influence on continuing labor relations and economies. Where Black people appear, they are primarily confined to vignettes emphasizing cultural contributions stripped of their labor connections (Negro Spirituals, a “mammy” stirring a pot in a homey tableau, a blues club, and so on).

It is a revealing, if unintentional, display of the intersection of race and capitalism in the mid-twentieth century. Although presumed whiteness powers many of this collection’s discussions celebrating economic development, more explicit and complex treatments of race can be found in programs recorded after landmark Civil Rights victories. However, much like the programs’ treatment of women (who are confined primarily to discussions of consumerism), when Black Americans are invoked by name, it is often in the context of social programs specifically targeting minority employment and urban communities. Most panelists are white and male, and even sympathetic speakers tend to treat African Americans as an anthropological Other to be measured and analyzed but not invited into conversation.

Deep South is only one of several series, including Pathways to Progress: The Great Lakes, that comment on regional economies and cultures. Sounds of Poverty offers a remarkable record of an educational program that introduced college students to the rural poor of Appalachia during the days of President Johnson’s War on Poverty and Community Action Programs. Despite overemphasis on student reactions and moments of paternalism, the series showcases the voices of those living in deep poverty offering their own cogent analysis of systemic governmental and business forces that perpetuate and profit from inhumane living conditions in Appalachia.

At first blush, Business Roundtable (not to be confused with the lobbying group founded in 1972), appears to be a panel discussion program primarily engaged in promoting pro-capitalist common sense laundered through the educational bona fides of its host (Alfred R. Seelye, Dean of Graduate School of Business at Michigan State University), a sometimes wonkish emphasis on policy and economic matters, and mild sporting disagreement among high-profile guests. It is this, of course: one memorable episode explores “the ethics of door-to-door selling” with none other than Amway president Richard DeVos. It turns out that not only is direct selling ethical, according to DeVos, it “provides millions of Americans with a chance to be their own anti-poverty program.” (If only someone would have told the Appalachia Volunteers.)

Other guests are generally better at hiding naked self-interest, speaking on topics woven throughout the economy and business collection, including inflation anxieties, taxes, the growing size of business organizations, the impact of foreign markets on the US, and the proper balance of power and influence among the state, business, and Labor. However, the program also joins Deep South and Sounds of Poverty in lending insight into regional economic concerns. Several guests represent Midwestern companies (Motorola, General Motors, Amway), and the show’s more revealing discussions—about business’s relationship to poverty, the euphemistically-labeled “urban problem,” and minority employment—often turn on Detroit.

Several industries are particularly well represented in the collection. Among them are computers and information technologies, which dutifully appear in discussions of automation, as well as automobiles and petroleum, which are invoked as a “bellwether” of the health of American business and a drain on the health of Americans and the planet.

No industry is better represented than education. In economy-minded discussions, schooling is positioned as the means to negotiate transformations in labor and leisure caused by the presumed inevitability of a shortened workweek due to automation. Whether these changes were considered chiefly a cultural or economic “problem” for education to solve depended on the speaker. Keynesian economists feared high unemployment; paternalistic elites fretted over what their fellow citizens would do with all that free time. The fault lines of these discussions will feel familiar to anyone in higher education today. Is it the responsibility of the university to educate for work or educate for life? Do universities or businesses bear responsibility for narrow pre-professional and vocational programs? And, especially from those worried that more leisure meant more drinking and maybe even more Communism, “How do we keep people from watching so much television?

Listening to these programs feels particularly rewarding when discussions turn on ideas that still feel fresh today. One of the most interesting suggestions, coming from one of the dullest programs, resolves the (presumed) cultural and employment consequences of automation in a single, compelling suggestion: government-funded, year-long sabbaticals for every worker at rate to maintain full employment despite less work to go around. In the hypothetical offered, a worker might use 9 months of their sabbatical studying topics of professional interest (construed broadly) at a college and spend the remaining three months attending to matters of personal importance. Acknowledging the gendered employment conditions of his period—namely, the difficulty of women to accrue equal years of service to men—the author gestures towards the need for a tailored system that would value the productive (and reproductive) contributions of all US citizens. Though only briefly sketched, it’s a remarkable reimagining of what both labor and education could look like when shared human needs and desires drive decision-making.

It’s also a reminder of just how much the entire visible spectrum of U.S. politics has narrowed and shifted rightward as monetarism and supply-side ideas pulled focus from embedded liberalism. A fascinating record of this transition unfolding is a program recorded in 1977. Ask President Carter, a live two-hour call-in show hosted by Walter Cronkite, allowed the American public to put questions directly to the president. Carter’s no Wolfman Jack, but the variety of questioners and topics paints a compelling portrait of popular understandings of shifting economic policy as it intersects with tax code, the ERA, foreign policy, Native American reparations, drug treatment programs, diversity hiring and myriad other topics. It’s crucial to remember that Pax Americana was funded by cruel foreign policy and legal Jim Crowism. However, revisiting these recordings also resurrects seemingly forgotten ideas and aspirations useful to us today: the recognition of Labor as a class with shared interests and (potentially) shared power, the role of the state in ambitiously addressing poverty and pollution, and full employment and the needs of working-class people—rather than the desires of finance—as the lodestar guiding economic decision-making.

Works Cited and Further Reading

Bird, William. Better Living: Advertising, Media, and the New Vocabulary of business Leadership, 1935-1955. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1999.

Blythe, Mark. Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Collins, Robert M. More: The Politics of Economic Growth in Postwar America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Jack, Caroline. “Producing Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose: How Libertarian Ideology Became Broadcasting Balance.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 62.3 (2018): 514-530.

Kit Hughes

Brochure for American Adventure Series, a TV program sponsored by Cold War free enterprise group The National Educational Program. Episode 8 promises viewers that the rich aren’t overly numerous or overly wealthy, while Episode 9 assures viewers that they, too, can be millionaires given the gumption. Although NAEB’s network manager declined to purchase the (TV) program for (radio) broadcast, this spiritual kin to Fifty Years is represented—along with other relevant materials—in NAEB document collections.

Visit the African American History theme in the collection for additional materials exploring race and the economy, like this script for The Last Citizen episode on Black employment.

Script for Report from Japan hosted by John Lerch (c1956). Although many economy-themed recordings focus on the U.S., documents hint at the extent to which U.S. postwar foreign policy sought to protect and expand capitalism abroad. See also the War and Civil Defense theme in the collection.

Promotional materials for People under Communism. Communism’s threat to the self-evident righteousness of capitalism pops up in docudramas and personal finance series alike.

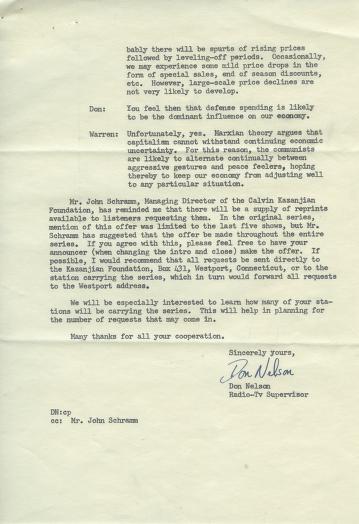

Another example of Communism's threat, in this letter from Don Nelson to Robert Underwood, Jr. (June 30, 1958) regarding “updates” made to Stretching Your Family Income to prepare it for NAEB distribution. See also World Politics and U.S. Government themes in the collection.